The actual ‘marrying’ of the strands is done only in the last lay, which when completed makes the rope. The ends where the strands are married should be staggered in different places. By this means rope can be made and extended in sections to a great length.

After your complete length of rope is laid up, pass it through fire, to burn off the loose ends and fibres. This will make your rope smooth and most, professional looking.

LAYING THE STRANDS

The strands lie on these crossbars as they are spun. When the strands have been spun to the required length, which should be no more than about a hundred feet, they are joined together by being held at the far end. They are then ready for laying together.

The turner, who is facing the cranks, twists the ends together anti-clockwise, at the same time keeping his full weight on the rope and which is being layed up. The layer advances placing the strands side by side as they turn.

Laying up is very fast when the layer is experienced. He quickly gets the feeling of the work.

It is important to learn to feed the material evenly, and lay up slowly, thereby getting a smooth even rope. Do not try to rush the ropemaking. If you do you will have uneven, badly spun strands, and ugly lays, and poor rope. Speed in ropemaking only comes with practice. At first it will take a team of three or four up to two hours or more to make a 50-yard length of rope of three lays, each of three strands, that is nine strands for a rope with a finished diameter of about 1 inch. With practice the same three or four people will make the same rope in 15 to 20 minutes. These times do not include time for gathering material.

In feeding, the free ends of the strands twist in the loose material fed in by the feeder. The feeder must move backwards at a speed governed by the rate at which he feeds. As the feeder moves backwards he must keep a slight tension on the strands.

MAKING ROPE WITH SINGLE SPINNER

Two people can make rope, using a single crank.

A portion of the material is fastened to the eye of the crank, as with the multiple crank, and the feeder holding the free ends of this strand against the bundle of loose material under his arm feeds in, walking backwards. Supporting crossbars, as used in a ropewalk, are required when a length of more than 20 or 30 feet is being spun.

FEEDING

If the feeder is holding material under his left arm, his right hand is engaged in continuously pulling material forward to his left hand which feeds it into the turning strand. These actions done together as the feeder walks backwards govern the thickness of the strands. His left hand, lightly closed over the loose turning material, must ‘feel’ the fibres ‘biting’ or twisting together.

When the free end of the turning strand, which is against the loose material under his arm takes in too thick a tuft of the material he closes his left hand, and so arrests the twist of the material between his left hand and his bundle. This allows him to tease out the overfull ‘bite,’ with his right hand, and so he maintains a uniform thickness of the spinning strand. There is a knack in 'feeding' and once you have mastered this knack you can move backwards, and feed with considerable speed.

THICKNESS OF STRANDS

Equal thickness for each of the strands throughout their length, and equal twist are important. The thickness should not be greater than is necessary with the material being used. For grass rope, the strand should not be more than ¼-inch diameter, for coarse bark or palm not more than 1/8 or 3/16, for fine bark, hair or sisal fibre not more than 1/8 inch.

For cords the strand should be no more than one-sixteenth inch in diameter.

Fine cords cannot be made from grass, unless the fibres are separated by beating out and ‘combing.’

The correct amount of twist is when the material is ‘hard,’ that is, the twist is tight.

FAULTS COMMON WITH BEGINNERS

There is a tendency with the beginner to feed unevenly. Thin wispy sections of strand are followed by thick hunky portions. “ Such feeding is useless. Rope made from such strands will break with less than one-quarter of the possible strain from the material.

The beginner is wise to twist and feed slowly, and to make regular, even strands rather than rush the job and try and make the strands quickly. Speed, with uniformity of twist and thickness, comes only with practice. In a short time when you have the ‘feel’ of feeding, you will find you can feed at the rate of from thirty to sixty feet a minute.

Thick strands do not help. It is useless to try and spin up a rope from strands an inch or more in thickness. Such a rope will break with less than half the potential strain of the material.

Spinning ‘thick’ strands does not save time in ropemaking.

LIANAS, VINES AND CANES

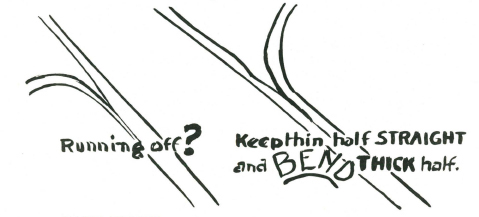

Lianas and ground vines are natural ropes, and grow in sub-tropical and tropical scrub and jungle. Many are of great strength, and useful for bridging, tree climbing and other purposes. The smaller ground vines when plaited give great strength and flexibility. Canes, and stalks of palms provide excellent material if used properly. Only the outer skin is tough and strong, and this skin will split off easily if you bend the main stalk away from the skin. This principle also applies to the splitting of lawyer cane (calamus), all the palm leaf stalks and all green material. If the split starts to run off, you must bend the material away from the thin side, and then it will gradually gain in size, and come back to an even thickness with the other split side.

BARK FIBRES

The fibres in many barks which are suitable for rope making are close to the innermost layer. This is the bark next to the sap wood.

When seeking suitable barks of green timber, cut a small section about three inches long, and an inch wide. Cut this portion right from the wood to the outer skin of the bark.

Peel this specimen, and test the different layers. Green bark fibres are generally difficult to spin because of ‘gum’ and it is better to search around for windfallen dead branches and try the inner bark of these. The gum will probably have leached out, and the fibres separate very easily.

Many shrubs have excellent bark fibre, and here it is advisable to cut the end of a branch and peel off a strip of bark for testing. Thin barks from green shrubs are sometimes difficult to spin into fine cord and it is then easier to use the lariat plait for small cords.

Where it is necessary to use green bark fibre for rope spinning (if time permits), you will find that the gum will generally wash out when the bark is teased and soaked in water for a day or so.

After removing from the water; allow the bark strips to partly dry out before shredding and teasing into fibre.

PLAITING

One man may require a considerable length of rope, and if he has no assistance to help him spin up his material he can often find reasonably long material (say, from 1 ft. to 3 ft. or more) and using this material he can plait (or braid) and so make suitable rope. The usual three plait makes a flat rope, and while quite good, has not the finish or shape, nor is it as ‘tight’ as the four or lariat plait. On other occasions it may be necessary to plait broad bands for belts or for shoulder straps. There are many fancy braids and plaits which you can develop from these, but these three are basic, and essential for practical woodcraft work.

A general rule for all plaits is to work from the outside in to the centre.

THREE PLAIT