But you observe that most birds that look for food in trees walk along the branches if they feed on fruit or flower blossoms and that the birds which feed on insects hop from branch to branch. Your final deduction is that birds which leave hopping tracks on the ground are birds which capture their food (in the form of insects) in the air, and so you make a rule, ‘hopping birds are insect eaters.’

In a general way this is true, but there are exceptions to all these general rules, and not all insect eating birds are hoppers, and not all ground hopping birds are insect eaters. (Consider your pet canary or the lovely painted finches, both of which are ground hopping, and both of which are grain or seed eaters.)

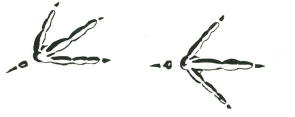

First, these are made by a bird which walks, not hops. Therefore it is accustomed to finding some, or all of its food on the ground. Being a ground feeding bird it may either–

feed on grain or fallen fruit,

feed on ground living creatures,

feed on flesh which it finds on the ground.

If it feeds on grain or fallen fruit it will not have the centre toe development that would be needed by a bird which had to scratch or dig for its food, nor would it have the rear claw development required by a flesh eater.

These, therefore, are the tracks of a ground feeding bird which, not having a digging claw, nor having talons, MUST be a grain or fruit eater.

Notice the development of the centre toe, and powerful claw. This is the mark of a ground feeding bird which scratches or digs for its food. It is a ground insect eater.

Here are four short and powerful toes with strong claws particularly on the hind toe. These are the talon feet of a ground feeder which lives on flesh. The foot tracks of a hawk and eagle, or a crow.

Naturally the place where the tracks are observed has a bearing on reading the correct answer, and if the tracks are found on the edge of a swamp or marsh the answer could be quite different from the answer if the tracks were observed a long way from water.

Tracks read as those of a grain eating ground feeder in forest land could correctly be read, if the same tracks were seen in mud, or by a reedy swamp edge, as tracks of a non-swimmimg, flesh-eating water bird.

Tracks such as these are easily and correctly read.

The web-footed track of a swimmer such as duck, swan, or geese.

ANIMAL TRACKS

In the animal kingdom the reading of tracks is equally simple. Consider these two–what is the feature you first notice?

It is the single or double thumb, the prehensile digit, which is the mark of every true tree climbing animal. Look at your own hand. Can you climb trees?

There are exceptions to this, as to the other general rules. For instance the tree climbing kangaroo of North Queensland, which has a prehensile tail. (Incidentally the domestic cat is not a true tree climber. It can ‘claw’ its way up a tree but. it cannot ‘climb’, as, say, a monkey climbs.)

In these tracks the claws of the centre toes are most prominent, and you are correct if your deduction is that these are the tracks of an earth digger, or burrower. The prehensile thumb is undeveloped, you notice.

The digging claws may be on fore or hind feet. Generally the fore feet show them most sharply, but whether on front or hind feet, they are the invariable mark of the digger.

These tracks show neither the prehensile thumb or the digging claw.

If you deduce that they are the tracks of flesh eating animals you would be correct, but why?

The answer is that the tracks show pronounced ‘toes,’ and that toes, when not used for climbing or digging, both of which call for special development, have another special use in that they give the foot a ‘springboard’ when running, and so you make the deduction that these are the tracks of fast running animals, and they are not grazing animals because no grazing animal shows ‘toes,’ unless you recognise the hoof of a cow or horse, sheep, etc., as ‘tips’ of toes or ‘toenails,’ which they really are.

These tracks are made by the grass and herbage eaters. Having neither climbing thumbs, to escape from enemies by climbing, nor digging tools, to escape by burrowing, their only means of escape is by running. Therefore you may decide that animals which have cloven hoofs are very fast running.

TRACKS INDICATE HABITS

Tracks made by animals on the ground, when read correctly, show the pattern of the animal’s habits. This calls for continuous and careful observation. It is important to recognise the fact that animals, and all living creatures, are as much creatures of habit as human beings. A particular animal will follow the same track to and from water day after day. It will hunt in the same area continually, and only leave the area when driven out by fire, flood or drought. Even then the move is only temporary, and it will return when conditions once again are favourable.

This ‘habit-forming’ characteristic of animals makes it possible for the experienced trapper to predict the animal’s movements, and so he selects the sites for his traps or snares, certain that they will be visited.

In the bush you will find many animal trails. These are the ‘roads’ of the bush creatures. They travel over them continually backwards and forwards, to and from their resting places to their feeding grounds and favourite wate-holes.

By observation of the number and newness of the tracks and droppings on these trails you can gauge the extent of animal traffic.

If you put an obstacle across one of these animal trails the animals will make a detour around the obstacle, always following the line of least resistance, and come back to the road again beyond the obstacle.

A very good example of these roads are the trails radiating from a meat ants’ nest. Exactly the same pattern is repeated in jungle, forest and grassland by all animals. Examine the upward side of a leaning gum tree, and if you see scratch marks of varying ages then the tree is a ‘tree road’ of possums or koalas, which either live in dead hollows or come to the tree nightly to feed on the young leaves or mistletoe berries. By looking up at a tree you can quickly tell if it is a feeding tree, or a living-quarters-tree. (The latter will show many dead limbs which are hollow, and therefore comfortable living quarters for possums and phalangers.)

ANIMAL WORLD’S 10 SENSES

As human beings we experience five senses. These are: Sight, Sound, Touch, Taste, Smell. These senses are the result of very highly specialised cells. One group of these cells in our eyes are stimulated by light and colour. As a result we ‘see.’ So it is with all our other senses. As human beings our eyes tell us more than any of our other senses, and all senses are directed to one end . . . LIVING. By living is meant, first the finding of food which it is safe for us to eat, and then keeping ourselves out of danger, and so keeping our race or species perpetuated.

In these end purposes of the senses the whole animal and vegetable kingdom differs in no way from us. It appears to this writer that some forms of life have developed senses which are quite beyond our human experience, and therefore rather difficult for us to understand.