The full list of these senses (sensitivities) might be as follows:

Note: These are purely the author’s observations, and not backed by scientific proof; consequently readers are advised not to accept these or the following remarks without reservation.

These sensitivities vary in their development between one creature and another. Here are a few examples of their existence which you can establish for yourself.

Sight Sensitivity

Sound Sensitivity

Tasta Sensitivity

Touch Sensitivity

Small Sensitivity

TEMPERATURE SENSITIVITY

Temperature Sensitivity

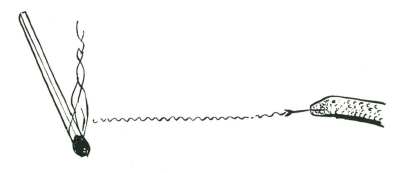

Temperature sensitivity can be observed if you put a leech in a screw-top covered glass jar, and cover the sides with thick paper. If you look down into the glass jar you will see the leech standing on its tail in the centre of the jar, weaving his upper end around. Put a burning stick a foot away from one side of the jar and he will loop towards it. Move the stick to the other side and he will change direction at once.

The leech cannot smell the stick, he cannot see it, nor can he hear it, but he is so sensitive to temperature that he can feel it. Because leeches feed on the blood of animals you can understand that their ‘temperature sensitivity’ will lead them to sources of food.

Snakes also have a highly-developed temperature sensitivity. A snake’s action of continually putting out its tongue is to guide it to warmer temperature, which to a snake may mean food (very much as if your eyes were habitually closed, but by flicking them open frequently you would be ‘guided’ towards light, and the light would in turn let you find food).

VIBRATION SENSITIVITY

Vibration Sensitivity

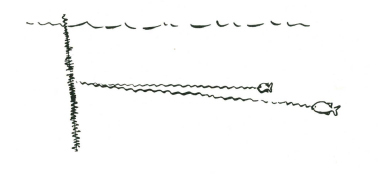

Vibration sensitivity seems to be most highly developed by water living creatures. It becomes evident by the actions of fish which show themselves to be attracted to the centre of small vibrations. This can be proven by throwing fine sand into still water. Small fish will instantly dart towards the sand, but if a heavy stone is thrown, they will scatter. A thread, fastened to a stone lowered beneath the water, if pulled taut, and lightly vibrated by rubbing, will also attract small fish. Cease the rubbing, which causes the vibration in the water and the fish will disperse. Rub, and they will be attracted again.

SUPERSONIC SENSITIVITY

Supersonic Sensitivity

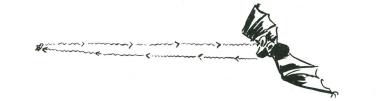

Throw a small pebble high into the air at dusk any summer evening, and watch its flight. Suddenly you will see a bat flash towards it, and then turn and fly away.

The bat sends out high pitched sound waves (beyond the pitch to which the human ear is tuned, but you may be fortunate enough to hear the ‘Chirp’ almost like a tightly-strung wire being plucked). These sound waves which the bat sends out in flight rebound when they meet any obstacle, even a tiny flying insect. The bat’s acute ears detect and follow the ‘echo’ which tells it “an insect for food is over there," and so the bat turns in its flight, all the time sending out its high-pitched soundwaves, and following up the echo till it finds the insect. This is 'super-sonic sensitivity.'

No doubt the echo from the pebble becomes too strong and the flying bat sheers off to avoid a collision.

Bats, which have low power vision, can fly through a maze of crossed wires unerringly because of this supersonic sense. With fruit eating bats, or flying foxes, there appears to be an extremely acute sense of smell, and the supersonic sense does not seem to have been highly developed.

Group Sensitivity

TELEPATHETIC OR ‘GROUP’ SENSITIVITY

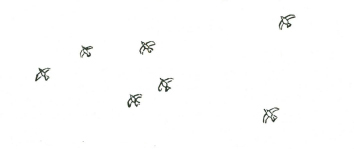

This sense is seen when you watch a flight of birds, pigeons movement is not made by one bird who acts first as a leader but simultaneously by all the birds in the flight. The only feasible explanation is that they have a group sensitivity,’ which, shared by all the birds in the flight, tells them to change direction.

DIRECTIONAL SENSITIVITY

Directional Sensitivity

Directional sensitivity is fairly well spread over the animal world. Many humans have this sense, which may have been acquired by training, but whatever the explanation they show a strongly marked sense of direction. Birds show it in their ability to 'home,' and in their migratory habits. Many species of fish show it in their breeding habits, returning to spawn in the same rivers in which they themselves were hatched.

SCENT SENSITIVITY HIGH WITH ANIMALS

Humans learn more through sight than through any other sense and as a result our sense of sight is more highly developed than any of our other senses.

As humans, we say, "There's a savage dog; look out he doesn't see you." This is because we think all animals like ourselves depend on sight.

The savage dog will not see you at first, but he will scent you, because his nose tells him more than his eyes. This high development of ‘smell sensitivity’ is more common with wild creatures than their development of sight.

It is difficult for us, as humans, to think as the wild animals think. For instance, if we saw a ‘snare’ or trap we would be cautious. For the trap to be effective it would have to be concealed from our sight, so that we could not see it.

An animal would smell your scent on the same trap. The sight of the trap would mean nothing to it, but the man scent attached to it, and lingering possibly for weeks after it was set up, would warn the wild animal, and your trap or snare would be quite ineffective.

Until you can realise that scent (of which you are completely unaware, because you have very poor’ ‘smell sensitivity’) tells an animal more than sight, your traps will catch nothing. This of course does not apply to all creatures. Birds and fishes are an exception, but it does apply to nearly all wild animals in their natural bush conditions.

Whilst the ‘man scent’ may spell ‘danger’ under some conditions, under other conditions where the animals have been accustomed to man and lives on his leavings (as rats, dogs and cats often do), the man scent, instead of being a warning signal, becomes a lure. Under true bush conditions, however, the ‘man scent’ is invariably a danger signal to all wild animals.

The man scent can be killed either by hiding it beneath a stronger smell, or by allowing it to weather off the trap or by removing it.

To ‘kill’ man scent you can either use a stronger scent of which the animal will not be suspicious, or you can use a scent which for one reason or another will attract the animal to your trap or snare.