The halyard is wrapped tightly round the flag, and then bent, and the loop pressed under the last rollings, held by the pressure of the cord against the bunting of the flag.

The toggle is fastened to the eye of the halyard on the mast, and the free end of the flag hoist is fastened to the other end of the mast halyard with a double sheet or crossover bend.

LOOP SPLICE

The strands are unlaid and laid side by side till the loop is the required length. The strands of the free ends are spliced into the ropes of the standing ends as for a short splice.

Toggle and eye–showing one application of splicing and whipping. Toggle is spliced and eye is whipped in sketch.

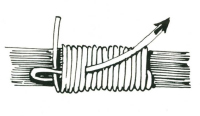

BINDING or WHIPPING

WHIPPING

Before the finish of the binding a loop formed from the end is laid under the binding at the start. This end is bent back to form a loop and the last six to twelve turns bind over this loop. At the last turn of the binding the cord is put through the loop and the free end of the loop is pulled tightly, thus drawing the end of the binding beneath the last turn.

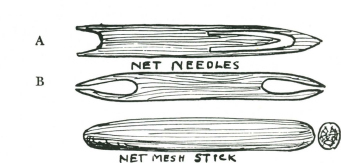

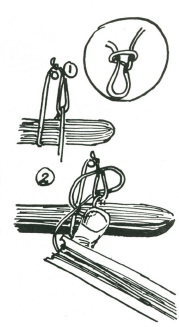

NETTING

Hammocks and nets are made by the use of a netting needle and a mesh stick. Either of the two types of netting needle shown in Fig. 1 are suitable and easily made from a thin piece of hardwood or bamboo. The netting needles may be about 8 to 9 inches long and from f inch to 1 inch wide. The mesh stick may be about 5 inches long, oval about ¾ x ¼. The netting cord is put on to the netting needles as for an ordinary shuttle with needle B, and with needle A the cord is looped round the pin in the centre of the eye.

At one end of the string tie a loop and place the knot on a conveniently high nail or hook. The mesh stick is put under the loop and the needle with cord passed through as in Fig. 3. The needle and cord are passed in front of the loop formed in Fig. 3 and under the original loop, while at the same time the other end of the cord is held on to the mesh stick with the thumb of the left hand. The knot is pulled taut.

A succession of these loops are formed until the requisite width is reached, then this first series of loops are placed through a rod or cord, and the loops are netted on to them until the requisite length is reached.

ANCHORING A PEG IN SAND OR SNOW

The only way to anchor a rope into soft sand is to attach it to a peg, and bury the peg in the sand.

Scrape a trench in the sand to a depth of between a foot and eighteen inches, deeper if high winds or very stormy weather are expected. Pass the rope round the centre of the peg; scratch a channel for it at right angles to the peg trench.

Fill in the trench and rope channel, and fasten the free end of the rope to the standing end with a stopper hitch, and pull taut. The buried peg should hold a tent rope in sand under all normal weather conditions.

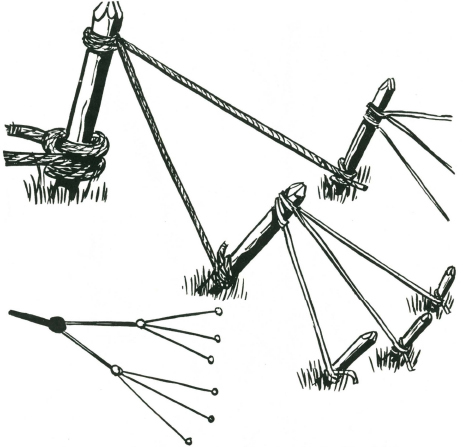

TO ANCHOR A ROPE IN OPEN GROUND

A secure anchor in open ground can be obtained by driving a stout stake well into the ground (see Chapter 3). The rope is later fastened to the base of this stake.

To the head of the stake two ropes are attached, and these are tied back to the ground level of two other stakes driven well into the earth a few yards behind the first stake.

To the heads of these two stakes three ropes are tied and these are fanned out and tied to the bases of three other stakes driven in behind the two stakes.

The main rope is now fastened to the base of the first stake.

This is appropriately called the “ONE - TWO - THREE” anchor and will hold a very great strain if the ground is “solid.”

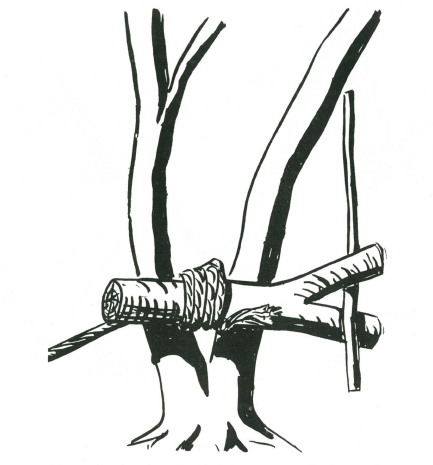

BUSH WINDLASS

A bush windlass, capable of taking a very heavy strain on a rope can be made by selecting a site where a tree forks low to the ground, with the fork facing the direction in which the pull is required. Alternatively, a stout fork can be driven in and anchored with the “1-2-3” method.

The windlass portion is a forked log. The forks are notched to take the lever (up to seven feet long). The rope is passed round the roller a few times so that it locks upon itself. (If the fork of the roller is long, the rope may pass through the fork.)

This type of bush windlass has many uses.

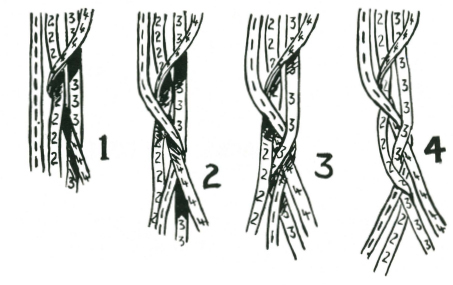

LARIAT OR ROUND PLAIT

1. Strand 4 is taken and passed over strands 2 and 3, and then turned behind the strand 2 and brought forward between 2 and 3.

2. Strand 1 (on the opposite side) is taken and passed over strands 2 and 4, and turned and brought forward between 2 and 4.

3. Strand 3 (on the side first worked) is taken and passed over strands 1 and 4, and turned and brought forward between the two.

4. Strand 2 is taken, passed over strands 1 and 3, turned and then brought forward between 1 and 3.

5. This sequence is repeated.

Lariat plaiting must be kept “tight,” that is, plaited close, and the flat strands must be turned as they twist round the two strands they have overlaid.

CHAPTER 7

TRACKS AND LURES

The signs animals leave on the ground can be more revealing than any book written by man, but unfortunately few people are able to see these signs and fewer still can read them.

To understand something of the behaviour of animals one must realise that the development of their senses is markedly different to mankind’s, and therefore where we obtain information through our eyes and ears, one animal may obtain the same information through its sense of smell and another through its ability to detect temperature changes, or through vibrations.

Where man communicates with man through speech, some forms of animal life communicate through telepathy. You see this in a flock of pigeons which turn in flight as one bird.

This book broadly deals with some of these special characteristics explaining how knowledge of the ‘sensitivity’ of the creature is useful”, and how the animal’s tracks provide a reliable indicator to its habits.

The whole area covered in this book, if practised, leads to a remarkable development of one’s powers of observation and deduction.

TRACKS AND THEIR MEANING

SIMPLE DEDUCTION

To be a successful trapper you must learn first to observe, and then to make the correct deduction from your observation. For example, if you see a bird move over the ground in a series of hops it would leave tracks like these.

You agree that these would be the tracks of a hopping bird?

To know that a bird hops on the ground tells you that it is normally unaccustomed to being on the ground. This is turn leads to the conclusion that, being unaccustomed to living on the ground, it therefore does not feed on the ground. Where else then might it feed?

Your answer would be that it may find its food either in the air or on shrubs or trees.