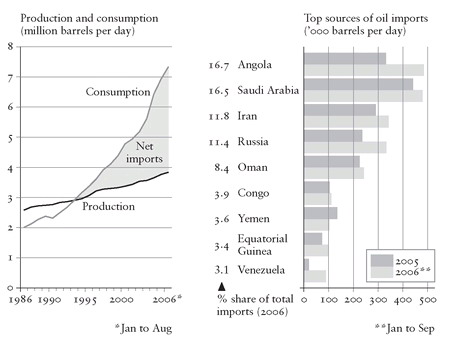

Finally, China ’s growth has been extremely resource-intensive, demanding of land, forest, water, oil and more or less everything else. Herein lies one of China ’s deepest problems. [482] The country has to support an extremely large and, for the most part, dense population in a situation where China is, and always has been, poorly endowed with natural resources. It has, for example, only 8 per cent of the world’s cultivated land and yet must sustain 22 per cent of the world’s population; in contrast, with only a fifth of China ’s population, the United States enjoys three times as much arable land and its farmland has been under human cultivation for one-tenth of the time of China ’s. [483] China ’s development, moreover, is rapidly exhausting what limited resources it possesses. Over the last forty years almost half of China ’s forests have been destroyed, so that it now enjoys one of the sparsest covers in the world. In 1993 it became a net importer of oil for the first time and now depends on imports for almost half its oil needs.

Figure 14. China’s growing dependency on oil imports.

As a result, China is becoming increasingly dependent on the rest of the world for the huge quantities of raw materials that it needs for its economic growth. It is already the world’s largest buyer of copper, the second biggest buyer of iron ore, and the third largest buyer of alumina. It absorbs close to a third of the global supply of coal, steel and cotton, and almost half of its cement. It is the second largest energy consumer after the US, with nearly 70 per cent produced from burning coal. In 2005 China used more coal than the US, India and Russia combined. In 2004 it accounted for nearly 40 per cent of the increase in the world demand for oil. [484] If the Chinese economy was to continue to expand at 8 per cent a year in the future, its income per head would reach the current US level in 2031, at which point it would consume the equivalent of two-thirds of the current world grain harvest and its demand for paper would double the world’s current production. If it were to enjoy the same level of per capita car ownership as the US does today, it would have 1.1 billion cars compared with the present worldwide total of 800 million; and it would use 99 million barrels of oil a day compared with a worldwide total production of 84 million barrels a day in 2006. [485] Of course, such a level of demand would be unsustainable in terms of the world’s available resources, not to mention its global environmental impact, which would be dire.

THE ENVIRONMENTAL DILEMMA

The effects of China ’s great paradox — namely, a huge abundance of human resources and extremely sparse natural resources — are being experienced throughout the world via the global market. China ’s surfeit of labour has meant that the prices of manufactured goods it produces have fallen drastically while the prices of those commodities that China requires rose dramatically until the onset of the credit crunch. Together these constitute what might be described as the new China-era global paradigm. The great beneficiaries of China ’s growth, hitherto, have been the developed countries, which have enjoyed a falling real price for consumer goods, and those nations which are major producers of primary products. The present global recession has seen a sharp fall in commodity prices, but there is little reason to believe that their rise will not be resumed once economic conditions start to improve again, driven by demand from China and India. The International Energy Agency has forecast that oil prices will rebound to more than $100 a barrel as soon as the world economy recovers and exceed $200 by 2030. [486] The resumption of rising commodity prices will make the present resource-intensive Chinese growth model increasingly, and ultimately prohibitively, expensive. Beyond a certain point, therefore, it will be impossible for China to follow the resource-intensive American model of progress; and that will happen long before China gets anywhere near the US’s present living standards. Indeed, it is already clear that China has decided to pursue a less energy-intensive approach.

China, however, will find it extremely difficult to change course. For centuries it has pursued a highly extractive approach towards a natural environment which, compared with that of most nations, is extremely poorly endowed with resources, most obviously arable land and water, as measured by population density. China, for example, has only one-fifth as much water per capita as the United States. Furthermore, while southern China is relatively wet, the north, home to about half the country’s population, is an immense parched region that threatens to become the world’s largest desert. [487] The Chinese state, from the great canals of the Ming dynasty to the Three Gorges Dam of the present, has long viewed the environment as something that can be manipulated for, and subordinated to, human ends. [488] The level of environmental awareness, on the part of government and people alike, has been very low, though this is changing rapidly, especially in the main cities. The poorer a society, moreover, the greater the priority given to material change at the expense of virtually all other considerations, including the environment. It is much easier for a rich society to make the environment a priority than a poor society — and China remains a relatively poor society. By 2015 China will only have reached the same standard of living as most Western countries achieved in 1960 and the latter, able to draw either on their own natural resources or those of their colonies, enjoyed the luxury of being able to grow without any concern for environmental constraints until they were already rich. [489] In European terms, China has torn from the eighteenth century to the twenty-first century in little more than three decades, pursuing a similar resource-intensive strategy, with the environment never more than a footnote. The result is a huge ecological deficit of two centuries accumulated in just a few decades: growing water shortages, over three-quarters of river water that is unsuitable either for drinking or fishing, 300 million people lacking access to clean drinking water, rampant deforestation, sixteen of the world’s twenty worst-polluted cities, acid rain affecting a third of Chinese territory, desert covering a quarter of the country, and 58 per cent of land classified as arid or semi-arid. [490]

China, still poor though it may be, will not have the option of postponing until the time it has achieved rich-country status two of its most pressing environmental issues. Willy-nilly, it will be obliged by cost pressures to shift towards less resource-intensive technologies. With the price of oil likely to increase considerably, at least in the medium term, China has already begun to seek ways of limiting its consumption of oil by, for example, imposing heavier taxes on gas-guzzlers and encouraging the development of alternative car technologies: [491] in Shanghai, which is China’s environmental leader, it now costs around £2,700 to register a new car. [492] Chinese economist Yu Yongding is certain the country will take action: ‘A billion Chinese driving gas-hogging SUVs is just a fantasy. Believe me, the Chinese are not so stupid. China has to and will reduce its reliance on oil imports.’ [493] The other irresistible environmental challenge is global warming. This will in due course oblige China to seek ways of limiting its production of CO 2 in the same manner that, in time, it will force every other country to seek alternative forms of growth. [494] Like India, China has resisted the idea that it should be subject to the same constraints as rich countries, on the grounds that the latter have been pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere for much longer and therefore bear a much greater responsibility for global warming. The major contributor to China ’s energy consumption, moreover, is not the domestic consumer, whose needs are minimal, but the export trade. The reality is that 40 per cent of China ’s energy goes into producing exports for Western markets: in other words, the West has, in effect, exported part of its own greenhouse emissions to China. [495] The minimal historical contribution made by the developing world to global warming was recognized in the Kyoto Protocol, which excluded them from its provisions, but the refusal of the United States and Australia to participate rendered the accord largely ineffectual. But with China having overtaken the United States as the biggest emitter of CO2 in 2007 [496] (even though its per capita CO2 emissions remain one-seventh of those of the US), [497]the idea that countries such as China and India can be excluded from any future agreement is no longer plausible, especially as the effects of global warming — already very evident in China itself, with accelerating desertification, reductions in agricultural yields, changing patterns of precipitation, the increased incidence of storms and droughts, and extreme weather like the prolonged snowfalls in central China in 2008 [498] — grow ever more serious. The environmental impact of energy use in China is particularly adverse because its dependence on coal — of a particularly dirty kind — is unusually high (60 per cent compared with 23 per cent in the US and 5 per cent in France) and carbon emissions from coal are proportionately much greater than from oil and gas. [499] Although the Chinese leadership has resisted the idea that the country should be subject to internationally agreed emission targets, it has accepted the scientific argument concerning global warming and, in both speeches and the growing volume of new environmental regulations, is displaying a heightened awareness of the problem. [500] In fact on paper China already has some of the most advanced laws in the world on renewable energy, clean production, environmental impact assessment and pollution control, though these still remain widely ignored in practice. [501] The government continues to resist the idea that environmental considerations should detract from the priority of rapid economic growth, but there is, nonetheless, widespread recognition of their urgency at the highest levels of the Chinese leadership. [502] The need for China to embrace a green development strategy, rather than relying on the old intensive model, has been powerfully argued by the influential Chinese economist Hu Angang. [503]

[482] Yu Yongding, ‘ China ’s Rise, Twin Surplus and the Change of China’s Development Strategy’, pp. 24-5.

[483] ‘What Will the World Gain from China in 20 Years?’ China Business Review, March/April 2003.

[484] Zha Daojiong, ‘China’s Energy Security and Its International Relations’, China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly, 3: 3 (November 2005), p. 44; and Yu Yongding, ‘The Interactions between China and the World Economy’, unpublished paper, Nikkei Simbon Symposium, 5 April 2005, p. 2.

[486] Javier Blas and Carola Hoyos, ‘IEA Predicts Oil Price to Rebound to $100’, Financial Times, 5 November 2008.

[487] Joseph Kahn and Jim Yardley, ‘As China Roars, Pollution Reaches Deadly Extremes’, New York Times, 26 August 2007.

[488] Elizabeth C. Economy, The River Runs Black: The Environmental Challenge to China’s Future (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2004), Chapter 2; Mark Elvin, The Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2004), pp. 460-71.

[489] John Warburton and Leo Horn, ‘ China ’s Crisis: A Development Perspective (Part One)’, 25 October 2007, posted on www.chinadialogue.net.

[490] Gaoming Jiang and Jixi Gao, ‘The Terrible Cost of China’s Growth’, 12 January 2007, posted on www.chinadialogue.net; Economy, The River Runs Black, p. 18; Warburton and Horn, ‘China’s Crisis: A Development Perspective (Part One)’.

[492] ‘Can Shanghai Turn Green and Grow?’, posted on www.bbc.co.uk/news; Lex, ‘Chinese Cars’, Financial Times, 6 July 2007.

[496] ‘China Gas Emissions “ May Pass US ”’, 25 April, 2007, posted on http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk. The International Energy Agency originally estimated that China would surpass the US in 2009 as the biggest emitter of the main gas linked to global warming.

[498] Jonathon Porritt, ‘ China Could Lead the Fight for a Cooler Climate’, 13 November 2007, posted on www.chinadialogue.net (accessed 2/6/08). The Chinese National Climate Change Assessment Report has predicted that by 2020 the average temperature in China will increase by between 1.1 °C and 2.1 °C.

[500] ‘Climate Key Issue for Wen at Asean Talks’, South China Morning Post, 19 November 2007.