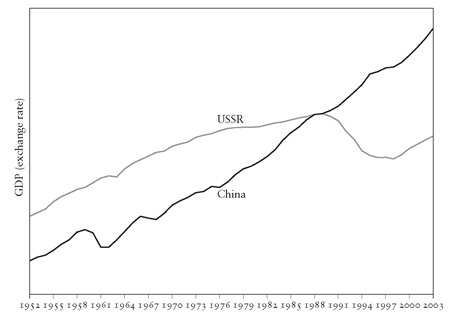

Figure 12. Economic performance of China and the USSR compared.

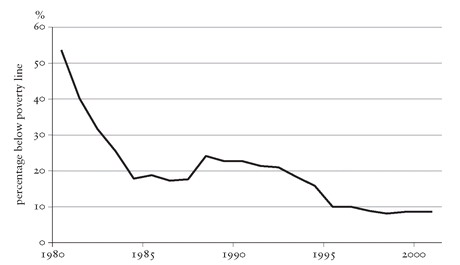

Given its scale and speed, China ’s economic transformation is surely the most extraordinary in human history, notwithstanding the sheer novelty of Britain ’s as the first. The government’s economic strategy, shrewd and far-sighted, has been very successful, [453] resulting in stellar economic growth and a rise in per capita income from $339 in 1990 to over $1,000 in 2003, with the not unrealistic aim that this will be doubled within ten years. [454] Economic growth is no longer confined to a few ‘islands’ but has spread out in waves to most provinces of China, albeit in sharply varying degrees. In a remarkably short space of time, China has become the centre of global manufacturing. ‘Made in China ’ has become synonymous with a host of mass-produced consumer products throughout the world. It produces two-thirds of the world’s photocopiers, shoes, toys and microwave ovens; half its DVD players, digital cameras and textiles; one-third of its DVD-ROM drives and desktop computers; and a quarter of its mobiles, television sets, PDAs and car stereos. [455] The country has borne witness to the greatest poverty-reduction programme ever seen, with the number of people living in poverty falling from 250 million at the start of the reform process in 1978 to 80 million by the end of 1993 and 29.27 million in 2001, thereby accounting for three-quarters of global poverty reduction during this period. [456]

Figure 13. The decline in poverty in China.

Although foreign multinationals dominate the country’s exports, home-grown Chinese firms like Haier, Konka, TCL, Huawei and Galanz have done well in such sectors as domestic appliances, television and telecommunications. Encouraged by the ‘Go Global’ campaign initiated by the government, the larger Chinese firms have begun to invest abroad and establish overseas subsidiaries. [457] China has made astounding economic progress, but its transformation is far from complete. It remains a work in progress. Although it is already the world’s second largest economy in terms of GDP (measured by purchasing power parity), this is primarily a consequence of population size rather than economic sophistication. Can China fulfil its enormous potential and become an economic superpower?

HOW SUSTAINABLE IS CHINA’S ECONOMIC GROWTH?

At the centre of any discussion about China ’s future role in the world — let alone talk of a Chinese century — lies the country’s economic prospects. A commitment to a growth rate of around 10 per cent remains fundamental to the government’s strategy. China needs to create 8 million jobs a year for its expanding urban population, plus another 15 million or so for the new rural migrants who seek urban employment every year. [458] Rapid economic growth will therefore remain at the heart of government strategy, with any serious and sustained drop below 8 per cent carrying the threat of serious social unrest. But, after a quarter-century, can this kind of growth rate be sustained? What are the limits to China ’s present growth path? Could its present strategy go badly wrong? And, crucially, what will be the impact of the global contraction that has transformed the short-term outlook for China?

The basic global competitiveness of the Chinese economy — the remarkable performance of its exports, which have driven economic growth and made the country such an attractive destination for foreign investment — will persist for many years to come because the condition on which it rests, the huge migration of rural labour into the cities, is destined to continue for several decades. Even if labour costs rise, as is already happening in the coastal regions and the Shanghai area, the inland provinces, fuelled by migrant rural labour, will help to contain inflationary pressures. [459] China ’s present economic path, thus, can potentially be sustained, at least in its broadest outlines, subject to significant reform, for at least the next five to ten years, perhaps longer. [460] But there are no guarantees. Yu Yongding, one of China ’s top economists, suggested in an interview in 2006 that there was a 30 per cent chance of things going seriously wrong. [461] The economy, given its high degree of exposure to trade, is very sensitive to exogenous developments. The global recession will be a major test of the extent to which the Chinese economy can maintain rapid economic growth in a situation where it can no longer depend to the same extent on Western export markets — prior to the global crisis, the European Union accounted for around 22 per cent of Chinese exports and the United States 18 per cent. [462]

In the context of the gathering recession, China ’s economic growth rate is estimated to have been 9 per cent in 2008 and is projected to fall to 6–8 per cent in 2009, from 12 per cent in 2006 and 2007, and an average of well over 10 per cent since 2002. The government is seeking to compensate for falling Western demand by encouraging domestic consumption, which accounts for around one-third of total output, and engaging in large-scale public expenditure, mainly on infrastructure, education and health. The government is fortunate in enjoying very strong finances and is therefore in a position to lavish considerable resources on stimulating the economy. The contrast, here, between the debt-laden, cash-impoverished, low-growth Western economies and the cash-rich, fast-growth, surplus-generating Chinese economy could hardly be greater, not to mention the fact that while the Western financial sector is effectively bankrupt, that of China is deposit-rich. This notwithstanding, the problems facing the Chinese economy are severe. In early 2009, it was estimated that 20 million migrant workers had already lost their jobs, with the prospects for those many millions planning to leave the countryside in search of work in the cities bleak. It is possible that the government’s efforts to compensate for the drastic fall in exports and declining foreign investment by increased public spending on infrastructure and social services, together with increased consumer expenditure, will ameliorate the effects of the downturn. Much will depend on the gravity of the recession in the West. If it results in a major contraction in the size of their economies, as seems possible, and if the recession persists for several years, the consequences for the Chinese economy are likely to be severe, with growth rates falling below 6–7 per cent, and perhaps even lower. In such circumstances, the government might face rising social unrest as unemployment escalates. The most benign scenario is one in which the Western recession is not too deep and relatively short-lived, and the Chinese government’s counter-measures are relatively effective. The most pessimistic scenario is one in which the Western recession bears strong echoes of the slump in the 1930s, both deep and protracted, the US resorts to protectionist measures against China and the Chinese government’s compensatory policies simply cannot cope with the collapse of its exports and inward foreign investment; such an outcome could presage social instability and might weaken the government’s own position.

[453] Interview with Yu Yongding, Beijing, 6 December 2005: Wang Gungwu, ‘Ration alizing China ’s Place in Asia ’, in Reid and Zheng, Negotiating Asymmetry, p. 5.

[454] Yu Yongding, ‘ China ’s Rise, Twin Surplus and the Change of China’s Development Strategy’, p. 2.

[456] Joseph Stiglitz, ‘Development in Defiance of the Washington Consensus’, Guardian, 13 April 2006.

[457] Oded Shenkar, The Chinese Century: The Rising Chinese Economy and Its Impact on the Global Economy, the Balance of Power and Your Job (New Jersey: Wharton School Publishing, 2006), p. 114.

[458] Yu Yongding, ‘China’s Macroeconomic Development, Exchange Rate Policy and Global Imbalances’, unpublished paper, Asahi Shimbun Symposium, October 2005, pp. 2–3.