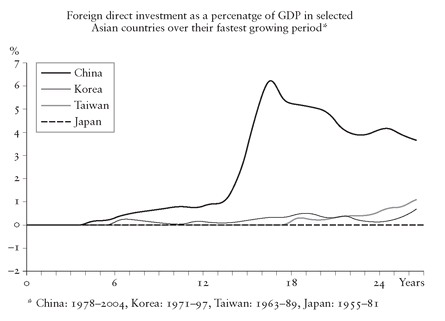

In response to the challenge posed by an increasingly globalized economy, the Chinese leadership, mindful of the need to accelerate the process of reform, did, however, opt for one important element of shock treatment. During the nineties, by dismantling tariff barriers and allowing huge flows of foreign direct investment — in contrast to the economic strategy pursued by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan — they created a brutal competitive environment in which domestic companies desperately sought to survive against far richer and more advanced Western and Japanese rivals. This rapid opening up enabled the Chinese economy to take advantage of enormous flows of foreign capital and had the merit of forcing Chinese companies to learn from the outside world, [440] but the cost was high, with many struggling to survive. While their North-East Asian neighbours enjoyed a prolonged period of protection from external competition, during which their companies were given time to develop, China, in comparison, had none. Chinese companies were obliged to sink or swim, and the conditions attached to China ’s subsequent membership of the WTO meant the state faced various restrictions on the extent to which it was permitted to help state-owned enterprises, although it found various ways of circumnavigating some of them. [441]

Figure 10. The role of foreign direct investment in China compared with other Asian tigers.

Although the earlier phase of reform concentrated on stimulating the growth of the rural economy, by the end of the eighties the centre of gravity had decisively shifted to the cities and the industrial economy. Already, during the eighties, the Guangdong economy became a microcosm of the future shape and comparative advantage of the fast-changing Chinese economy, with Hong Kong entrepreneurs moving their manufacturing operations out of the city-state to neighbouring Guangdong province in order to take advantage of far cheaper labour; as a result, Guangdong rapidly became Hong Kong ’s manufacturing base. This process quickly spread north and east-wards during the course of the nineties, its magnitude transformed by the flood of Western and Japanese direct investment at the end of that decade in anticipation of China ’s membership of the WTO in 2001. Just as China pursued an open policy on trade, it adopted a similar approach towards inward investment. Since 1978 China has received $500 billion in foreign direct investment, ten times the total accumulated by Japan between 1945 and 2000. In 2003 China became the world’s largest recipient of foreign direct investment, overtaking the United States. [442] The inward investment was mainly ploughed into the local subsidiaries of foreign multinationals with the purpose, following the example of Hong Kong, of exploiting the huge resources of cheap labour in order to make exports as globally competitive as possible. Foreign firms are now responsible for up to 60 per cent of all Chinese exports, and dominate high-tech exports with a share of around 85 per cent. [443] China, in the process, has become the ‘workshop of the world’, by far the cheapest national base for low- and medium-end manufacturing on the planet.

As a result of the systematic lowering of tariffs, one of the singular features of the Chinese economy is its huge exposure to foreign trade, which accounts for around 75 per cent of GDP, far in excess of other major economies like the United States, India, Japan and Brazil, where the figure is 30 per cent or less. [444] Such exposure makes China that much more significant in the global economy; it also leaves the country more vulnerable to external shocks such as a global downturn, a US recession or growing protectionist sentiment in the West.

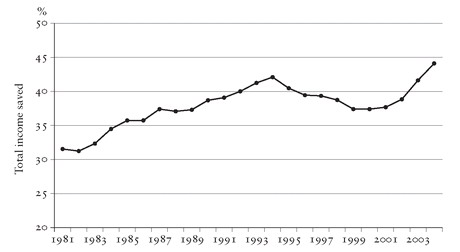

China is in the midst of what Marx described — writing of the British Industrial Revolution — as primitive accumulation, or what we now know as economic take-off: the process in which the majority of the working population moves from the land to industry, from the countryside to the cities. Between 1952 and 2003, agriculture’s share of GDP fell from 60 per cent to 16 per cent and its share of employment from 83 per cent to 51 per cent. [445] Although it took China only 10 years to double its per capita output (1977- 87) — a measure of the speed of economic take-off — compared with 58 years for the UK, 47 for the US and 11 for South Korea, after three decades of economic growth averaging 9.5 per cent, [446] around half the people still work on the land. It is estimated that even 20 years hence around 20 per cent of the population will still live in the countryside. [447] A crucial consequence of this relatively ‘limitless’ supply of rural labour is that wages for unskilled work will remain depressed for several decades to come: in other words, for much longer than was the case with the earlier Asian tigers. [448] This does not mean that wages in the more developed regions like Guangdong will remain low: on the contrary, as we have seen, they have already risen considerably. [449] But in the poor, still largely rural, interior provinces they will continue to be much lower, which is the reason why low-end manufacturing is steadily relocating there. The rapid growth of the Chinese economy since 1978 has largely been a function of the extremely high rate of investment, in the region of 40 per cent of GDP for many years, presently edging closer to 45 per cent, and soon to approach 50 per cent. [450] Such an extremely high rate of investment has been possible because of the similarly high rate of domestic savings, running at around 40 per cent of GDP, which, together with inward investment, has provided the main funds for China ’s take-off. In 2001 the average Chinese household saved 25.3 per cent of its disposable income, compared with 6.4 per cent in the US in 2002. The huge savings made by Chinese families have played a key role in funding the country’s rise (see Figure 11). [451]

Figure 11. China’s savings rate from 1981.

It is instructive to compare the experiences of China and Russia because both were confronted with the problem of how to move from a command to a market economy. Russia relied on the preferred Western prescription of shock therapy, which in the nineties led to hyper-inflation, large-scale capital flight, currency collapse and default on foreign debt. In contrast China, by pursuing a more gradualist approach, avoided hyper-inflation, the government remained internationally creditworthy and there was no capital flight. While in Russia the state sector was sold off at knock-down prices to assorted cronies, the state sector in China, rather than being subject to wholesale privatization, was contracted by a slow process of attrition. In Forbes Magazine ’s listing of the world’s 100 richest billionaires in 2007, thirteen were in Russia and none in China. In 1990, China’s GDP was less than twice as big as Russia’s; by 2003 it was more than six times as large. The subsequent rebound in the Russian economy, prior to the global downturn, was largely a result of the increase in the price of its oil and gas exports. The Chinese leadership has displayed great patience and considerable competence at tackling a succession of difficult and elusive problems. At the end of the nineties, for example, the government was faced with three extremely difficult domestic issues: closing a very large number of loss-making state enterprises; overhauling the state banks, which were saddled with a large and rising proportion of non-performing loans, mainly to indebted state enterprises; and strengthening the weak fiscal position of central government. A decade later, the government is well on the way to overcoming these problems, having greatly reduced the problem of indebted state enterprises, transformed the condition of the banking system and improved its own finances. [452]

[440] Yu Yongding, ‘ China ’s Structural Adjustment’, unpublished paper, Seoul Conference, 2005, p. 2.

[441] Nolan, Transforming China , p. 61; Lex, ‘ China and International Law’, Financial Times, 30 April 2008.

[442] Clyde Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East (New York: Basic Books, 2006), p. 61.

[443] George J. Gilboy, ‘The Myth behind China ’s Miracle’, Foreign Affairs, July/ August 2004, pp. 4–5.

[449] ‘ Guangdong Factories Drop Cheap for Chic’, South China Morning Post, 17 March 2008; ‘End of an Era for Pearl River Delta’, South China Morning Post, 9 February 2008.