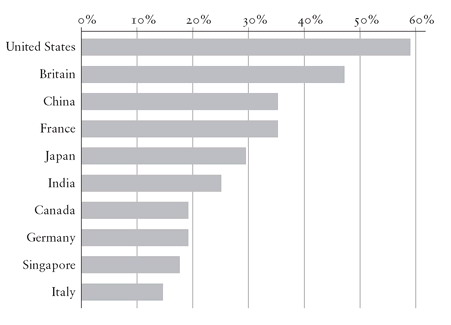

Among China ’s strengths is the fact that it possesses a large number of highly educated professionals as well as a strong educational ethos. [523] The country is now producing over 900,000 science, engineering and managerial graduates every year. In addition a significant number of Chinese students are educated at the top American universities, although a sizeable proportion choose to stay on and work in the US afterwards: Chinese, for example, account for around one-third of all professional and technical staff in Silicon Valley. [524] The Chinese government has been intensifying its efforts to persuade overseas Chinese to return home: 81 per cent of the members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and 54 per cent of the Chinese Academy of Engineering are now returned overseas scholars. [525] Overall, it is estimated that around 20 per cent of Chinese professionals working overseas have now returned, thus repeating a similar pattern that occurred with earlier Korean migration. [526]

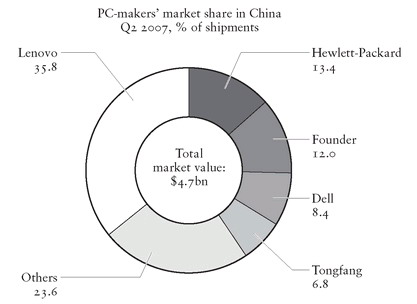

Figure 17. Lenovo commands largest share of China’s PC market.

Figure 18. Percentage of multinationals with R & D centres in various countries in 2006.

The technological picture, as in virtually every other aspect of China ’s development, is extremely uneven, combining the primitive, the low-tech, the medium-tech, and pockets of advanced, even very advanced, technology. [527] There is, however, little reason to doubt that China will scale the technological ladder. [528] This, after all, is exactly what happened with other Asian tigers, most obviously Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, all of which started on the lowest, imitative rungs, but which now possess impressive technological competence, with Japan and South Korea well in advance of most European countries. The evidence is already palpable that China is engaged in a similar process and with the same kind of remarkable speed. [529] It is an illusion to think that China will be trapped indefinitely in the foothills of technology. In time it will become a formidable technological power.

China ’s growing ability to climb the technological ladder, however, does not imply that it will be successful in building a cluster of successful international firms. Until very recently, China fared very poorly in the Fortune Top 500 global firms. Of the world’s top ten brands, only one, China Mobile, is Chinese, and of the top 100, only four are Chinese. [530] However, the picture is beginning to change. In 2006, 2 °Chinese firms featured in the Fortune Top 500, by 2007 the number had risen to 24, and by 2008 to 29, including four state-owned banks, the largest construction companies and the oil giant Sinopec. This compares with 153 from the US, 64 from Japan, 39 from France, 37 from Germany, 34 from the UK, and 15 from South Korea. Major Chinese manufacturers like Haier, Galanz and Konka, which have cornered the lion’s share of the domestic market in consumer appliances and also made serious inroads in many developing markets, however, still remain, in comparison with their American, European, Japanese and Korean competitors, very weak in terms of size, management, governance, and research and development. [531]

Unlike the early Asian tigers, Chinese firms were unable to postpone their move into foreign markets and production until they had acquired a solid financial foundation, technical competence, a well-established brand and high profitability based on domination of their home market; the major motive for many Chinese companies going abroad, in contrast, has been their desire to escape the cut-throat competition — much of it foreign — and sparse profits of the domestic market following China’s accession to the WTO. [532] Peter Nolan, an expert on Chinese business, has argued that it will be extremely difficult for Chinese companies to make the A-list of multinationals precisely because they have not had the chance to build themselves up domestically behind a protectionist wall. He also suggests that over the last twenty years there has been a global business revolution, as a result of which Chinese companies, far from catching up, have fallen even further behind the top international firms, making their task even more difficult. [533]

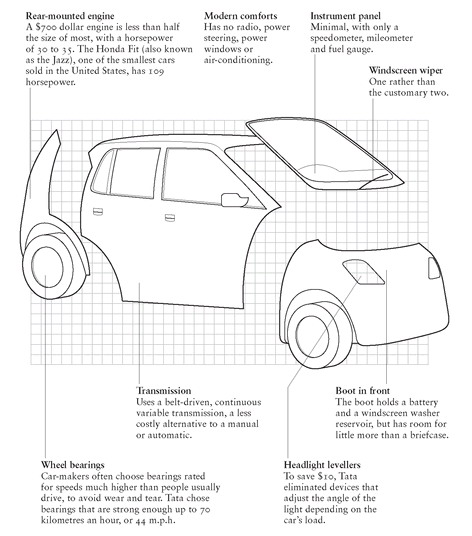

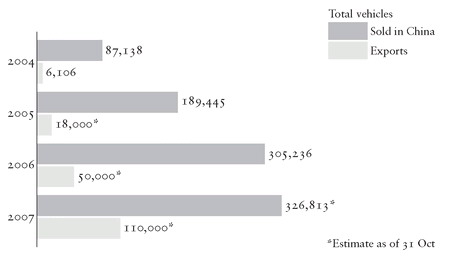

If China fails to produce a cluster of major international firms it will stand in sharp contrast to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. [534] But it is premature to think in these terms. However difficult and different the circumstances China faces, it is already busy inventing its own path of development, as Britain did as the pioneer country, the United States as the inventor of mass production, and Japan as the innovator of a new kind of just-in-time production. What might this be? In the Chinese car market, the more expensive sectors are overwhelmingly the preserve of European, American and Japanese firms, but emergent Chinese firms like Chery and Geely dominate the lowest segment. [535] Chinese firms are able to produce cars much more cheaply than foreign producers because they use a modular, or mix and match, approach rather than the integrated method of production for which Japanese firms are renowned. Firms such as Geely and Chery utilize a range of parts which are borrowed, copied or bought from foreign companies. The end product is of relatively low quality but extremely cheap. The Chevrolet Spark, which is very similar to the Chery QQ, sells for twice the price. A similar kind of approach can be seen with the Tata Nano in India, which sells for less than $2,500, half the price of the next cheapest car on the market. [536] Modular — or open architecture — production is extremely well suited to a developing country, being relatively labour-intensive and very difficult, if not impossible, for Western and Japanese firms to imitate. In the Chinese case, it was first developed by the motorcycle, truck and consumer appliance industries and then adapted by the domestic car firms. [537] The fact is that in China, as in most other developing countries, the low end of the market will remain by far the largest sector for many years to come. Despite fearsome competition from foreign producers, Chinese car manufacturers have very slowly been increasing their share of the Chinese market, currently the world’s second largest: in 2006 their combined market share was 25.6 per cent, just behind the total Japanese share of 25.7 per cent and ahead of the aggregate European share of 24.3 per cent, with Chery and Geely, the two largest, enjoying a combined share of around 10 per cent.

Figure 19. How to make a cheap car, Indian-style: the Tata Nano.

[523] Nicholas D. Kristof, ‘The Educated Giant’, International Herald Tribune, 29 May 2007.

[525] Zhou and Leydesdorff, ‘The Emergence of China as a Leading Nation in Science’, p. 84.

[526] Wilsdon and Keeley, China, pp. 30–31; Geoff Dyer, ‘How China is Rising Through the Innovation Ranks’, Financial Times, 5 January 2007; Shenkar, The Chinese Century, p. 74; Gittings, The Changing Face of China, p. 263.

[527] Suntech Power Holdings, for example, has grown big and successful as China’s leading maker of silicon photovoltaic solar cells; Thomas L. Friedman, ‘China’s Sunshine Boys’, International Herald Tribune, 7 December 2006. Also ‘China Climbs Technology Value Chain’, South China Morning Post, 30 March 2007; Victor Keegan, ‘Virtual China looks for Real Benefits’, Guardian, 1 November 2007; ‘High-tech-Hopefuls: A Special Report on Technology in India and China’, The Economist, 10 November 2007.

[529] ‘ China Makes a Move into High-value Exports’, International Herald Tribune, 7 June 2007.

[530] ‘Faced with a Steep Learning Curve’, Financial Times special report on global brands, 23 April 2007.

[535] Chunli Lee, ‘ China Targets Detroit ’, World Business, April 2006, pp. 30–32. Local car-makers dominate cars priced below RM 100,000 ($12,000); foreign car-makers all those above. Ibid., pp. 30–32; also ‘Minicars Drive Geely’, South China Morning Post, 16 September 2006.

[536] ‘ India ’s Car for the Common Man’, posted on www.bbc.co.uk (accessed 13/5/08). Also Anand Giridharadas, ‘Spirit of Gandhi Inspires a Bargain’, International Herald Tribune, 8 January 2008.

[537] Chunli Lee, ‘Trends of Open Product Architecture and Internationalisation of Private Companies in the Chinese Automobile Industry’, Aichi University Economic Review, 169 (November 2005), pp. 3–5, 10–14, 23-5; Chunli Lee, Jin Chen and Takahiro Fujimoto, ‘Chinese Automobile Industry and Product Architectures’, unpublished paper; Chunli Lee, ‘Product Development by Chinese Automakers: The Dilemma of Imitation and Innovation’, unpublished working paper for International Vehicle Program, MIT, July 2007, pp. 1-30.