WEIGHT OF NUMBERS

At the height of the British Empire in 1913, Britain accounted for only 2.5 per cent of the world’s population, while Western Europe represented 14.6 per cent. By 2001 Western Europe ’s share had fallen to 6.4 per cent. In 2001, when the United States was the world’s sole superpower, it comprised a mere 4.6 per cent of the world’s population. The proportion accounted for by the West as a whole — including Eastern Europe and countries like Australia but excluding the former USSR — was 13.9 per cent in 2001. China, in contrast, comprised 20.7 per cent of the world’s population in 2001. [1250] Moreover, whatever the obvious commonalities — historical, cultural and ethnic — that serve to link and cohere the Western world, this is very different from the unity and cohesion that China enjoys as a single nation. The true comparison is China ’s 20.7 per cent against the US ’s 4.6 per cent. In other words China, as the world’s leading country, will enjoy a demographic weight that is qualitatively different from that of any previous hegemonic power in the modern era.

The basis of democracy is that numbers count. Hitherto this proposition has been confined within the boundaries of each individual nation-state. It has never found any form of expression at a supranational, let alone global, level, with the possible exception of the United Nations General Assembly — which, predictably, enjoys virtually no power. Institutions like the IMF and the World Bank have never sought to be democratic but instead reflect the economic and political clout of those countries that founded them, hence the dominance of the United States and to a lesser extent Europe, with the US enjoying in effect the power of veto. The Western world order has — in its post-1945 idiom — placed a high premium on democracy within nation-states while attaching zero importance to democracy at the global level. As a global order, it has been anti-democratic and highly authoritarian. The emergence of China as the globally dominant nation is very unlikely to usher in a new kind of democratic global governance, but the rise of developing nations like India, Brazil and Russia, along with China, should herald, in a rough and ready way, a more democratic global economy. The huge mismatch between national wealth on the one hand and size of population on the other that has characterized the last two centuries will be significantly reduced. For the developing world, including the most populous countries, poverty has meant marginalization or effective exclusion from global decision-making; economic power, in contrast, is a passport to global enfranchisement. Or, to put it another way, a global economic regime based on the BRICS (namely Brazil, Russia, India and China), together with other developing countries, will be inherently more democratic than the Western regime that has previously prevailed. Furthermore, the fact that China, as the top dog, is so numerous will in itself introduce a more democratic element, albeit in the crudest sense, to the global polity. One-fifth of the world, after all, is rather more representative than the US ’s 4.6 per cent. [1251]

That China, as a global power, will be so numerous will have many consequences. China will exercise a gravitational pull and also have a centrifugal impact on the rest of the world. There will be many aspects to this push-pull phenomenon. The size of the Chinese market means that, in time, it will inevitably become by far the world’s largest. As a result, it will also assume the role of de facto yardstick for most global standards and regulations. The size of its domestic market will also have the consequence that Chinese companies will be the biggest in the world, as will the Chinese stock exchanges. In the 1950s Europeans were astounded by the scale of all things American; in the future, these will be dwarfed by the magnitude of all things Chinese. Even the position of Las Vegas as the gambling capital of the world is under threat, with the gaming revenues of Macao on the verge of overtaking those of the former by 2007. An example of China ’s centrifugal impact is offered by Chinese migration. China will be a net exporter of people, as Europe was until the mid twentieth century, but unlike the United States, which remains a net importer. [1252] A small insight into what this might mean is provided by the rapid migration of hundreds of thousands of Chinese to Africa in the first few years of the twenty-first century. If the economic relationship between China and Africa continues to develop along the same lines in the future, Chinese settlers in sub-Saharan Africa could come to represent a significant minority of its population. It is not inconceivable that large numbers of Chinese might eventually migrate to Japan to compensate for its falling population, though this would require a sea-change in Japan ’s attitude towards immigration. It is estimated that the Chinese minority there, legal and illegal, presently numbers up to 400,000. [1253] The Chinese are already a rapidly growing minority in Russia, especially in the Russian Far East. In comparison with Americans, then, if not necessarily with the Europeans before them, the Chinese will be far more ubiquitous in the world.

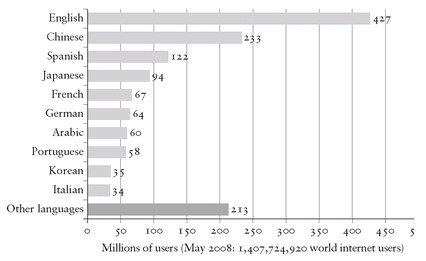

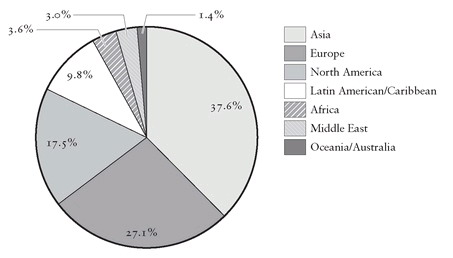

Another example will be provided by tourism. The United Nations World Tourism Organization predicts, rather conservatively, that there will be 100 million outward-bound Chinese tourists by 2019 (compared with almost 28 million in 2004), and an estimated global total of 1.6 billion in 2020. The World Travel and Tourism Council has predicted that by 2018 the value of Chinese tourism will almost be as great as that of the United States. The impact will be greatest in East Asia, especially South-East Asia, and Australia, where many destinations will seem as if they have been taken over by Chinese tourists, a phenomenon that hitherto has been almost exclusively Western, but which will happen on a far grander scale with the Chinese. [1254] The Chinese language, similarly, will assume global importance simply because it has so many native speakers; this will contrast with recent periods of history when the USSR and later Japan were riding high but which, partly because of their relatively small populations, had little linguistic impact, apart from on Eastern Europe in the case of the Soviet Union, outside their own borders. In terms of language, it is already possible to glimpse the future through those who use the internet. Though the proportion of China ’s population who are internet users is far smaller than that in the United States, by 2008 the number of Chinese internet users had already overtaken the number of American users. [1255]

Figure 44. Top ten internet languages, May 2008.

Figure 45. World internet users, March 2008.

[1250] Angus Maddison, The World Economy: Historical Statistics (Paris: OECD, 2003), p. 258.

[1251] For a very interesting article on the decline of the United States, and the West, in this context, see Niall Ferguson, ‘ Empire Falls ’, October 2006, posted on www.vanityfair.com.

[1252] Angus Maddison, The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective (Paris: OECD,2006), p. 128.

[1253] Howard W. French, ‘For Old Rivals, a Chance at a Grand New Bargain’, International Herald Tribune, 9 February 2007.