There are many other aspects of Chinese history which will reconfigure the global discourse: the fact, for example, that China has been responsible for so many of the inventions that were subsequently adopted elsewhere, not least in the West, will help to dispel the contemporary myth that the West is history’s most inventive culture. For our purposes here, the voyages of Zheng He, which predated those of Europe ’s great maritime explorers like Christopher Columbus, can serve as an example for this process of reconfiguration. It is widely accepted that, in ships that dwarfed those of Europe at the time, Zheng He embarked on a series of seven voyages that took him to what we now know as Indonesia, the Indian Ocean and the east coast of Africa in the early fifteenth century. The voyages of the great European explorers like Vasco da Gama and Columbus marked the beginning of Europe ’s long-running colonial era. For the Chinese, on the other hand, Zheng’s voyages had no such consequence. There was no institution in Ming China that resembled a Navy Department and therefore, as the historian Edward Dreyer suggests, ‘there was no vested interest to argue the case for sea power or for a blue water strategy, nor did China exercise what later naval theorists would call “control of the seas” even during the period of Zheng He’s voyages.’ [1234] Zheng’s voyages never had a sequel: they proved to be the final curtain in the Ming dynasty’s maritime expeditions as China once again slowly turned inwards. Zheng’s missions were neither colonial nor exploratory in intent: if they had been, they would surely have been repeated. They were influence-maximizing missions designed to carry out the very traditional aim of spreading China ’s authority and prestige in what was its known world. The Chinese had no interest in exploring unknown places, but in making peoples in its known world aware of the presence and greatness of the Chinese empire. Zheng He’s expedition lay firmly within the idiom of the tributary state system, though his journeys took him much further afield than had previously been the case. [1235]

History is always subject to interpretation and reinterpretation, constantly reworked in the light of a contemporary context. Given their extraordinary nature, and bearing in mind subsequent European exploits, it is not surprising that both the purpose and reach of Zheng’s expeditions has been the subject of much conjecture. As China again seeks a closer relationship with South-East Asia, the fact that China has recently sponsored several commemorative exhibitions of Zheng He’s expeditions in various ASEAN countries is predictable: [1236] as it turns outwards once more, it remembers and reminds the world of the last such great occasion. The British historian Gavin Menzies has taken the process several steps further by arguing that the Chinese were the first to discover the Americas in 1421 and also discovered Australia. [1237] While there has been much interest in, though little support for, the idea that the Chinese discovered America, when President Hu Jintao visited Australia in 2003 he gave implicit endorsement to the idea that China discovered Australia when, in an address to a joint meeting of the Australian parliament, he declared: ‘Back in the 1420s, the expeditionary fleets of China’s Ming dynasty reached Australian shores.’ [1238] These kinds of claims are likely to increase as Western-written history is contested by the growth in Chinese-written history and as China seeks to burnish its contemporary image not only by promoting its own past but also, no doubt, aggrandizing and embellishing it. The Chinese ambassador to South Africa suggested to Africans in 2007 that:

Zheng took to the places he visited [in Africa] tea, chinaware, silk and technology. He did not occupy an inch of foreign land, nor did he take a single slave. What he brought to the outside world was peace and civilization. This fully reflects the good faith of the ancient Chinese people in strengthening exchanges with relevant countries and their people. This peace-loving culture has taken deep root in the minds and hearts of Chinese people of all generations. [1239]

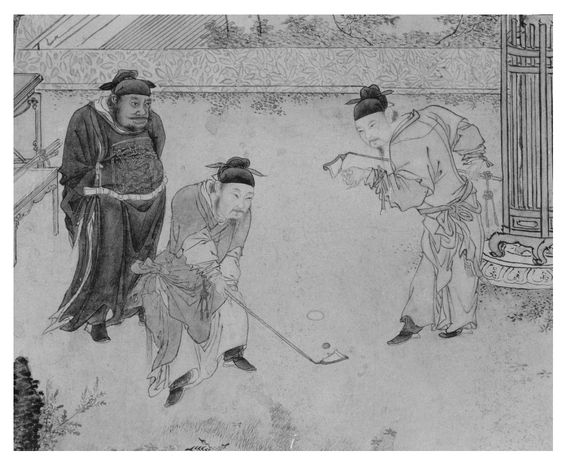

On a light-hearted note, there is evidence to suggest that the game of golf originated in China. A Ming scroll entitled The Autumn Banquet, dating back to 1368, shows a member of the imperial court swinging what resembles a golf club at a small ball, with the aim of sinking it in a round hole. In Chinese the game was known as chuiwan, or ‘hit ball’. [1240] It is reasonable to surmise that many of the sports that have previously been regarded as European inventions, and especially British, actually had their origins in other parts of the world: the British, after all, had plenty of opportunity to borrow and assimilate games from their far-flung empire and then codify the rules. As we move beyond a Western-dominated world, these kinds of discoveries and assertions will become more common, with some, perhaps many, destined to gain widespread acceptance.

BEIJING AS THE NEW GLOBAL CAPITAL

At the turn of the century, New York was the de facto capital of the world. Nothing more clearly illustrated this than the global reaction to 9/11. If the same fate had befallen the far more splendid Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, the disaster would have been fortunate to have commanded global headlines for twelve hours, let alone months on end. New York ’s prominence owes everything to the fact that it is the financial capital of the world, the home of Wall Street, as well as a great melting pot and the original centre of European immigration. New York ’s global status is, however, largely a post-1945 phenomenon. In 1900, during the first wave of globalization, the world’s capital was London. And in 1500, arguably Florence was the most important city in the world (though in that era it could hardly have been described as the global capital). In 1000 perhaps Kaifeng in China enjoyed a similar status, albeit unknown to most of the world, while in AD 1 it was probably Rome. [1241] Looking forward once again, it seems quite likely that in fifty years’ time — and certainly by the end of this century — Beijing will have assumed the status of de facto global capital. It will face competition from other Chinese cities like Shanghai, but as China ’s capital, the centre of the Middle Kingdom and the home of the Forbidden City, Beijing ’s candidature will be assured, assuming China becomes the world’s leading power.

But this is not simply a matter of Beijing ’s status. We can assume that Chinese hegemony will involve at least four fundamental geopolitical shifts: first, that Beijing will emerge as the global capital; second, that China will become the world’s leading power; third, that East Asia will become the world’s most important region; and fourth, that Asia will assume the role of the world’s most important continent, a process that will also be enhanced by the rise of India. These multiple changes will, figuratively at least, amount to a shift in the earth’s axis. The world has become accustomed to looking west, towards Europe and more recently the United States: that era is now coming to an end. London might still represent zero when it comes to time zones, a legacy of its once-dominant status in the world, [1242] but the global community will increasingly set its watches to Beijing time.

[1234] Edward L. Dreyer, Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming Dynasty, 1405-1433 (New York: Pearson Longman, 2007), p. 170.

[1235] My thanks to Zhang Feng for these observations. See also ‘Columbus or Zheng He? Debate Rages On’, China Daily, 19 July 2007, especially the views of Ge Jianxiong.

[1237] Gavin Menzies, 1421: The Year China Discovered The World (London: Bantam Books, 2003).

[1238] Geoff Wade, ‘Don’t Be Deceived: Our History Really is Under Serious Attack’, Canberra Times, 27 April 2006.

[1240] Patrick L. Smith, ‘Museum’s Display Links the Birth of Golf to China ’, International Herald Tribune, 1 March 2006.