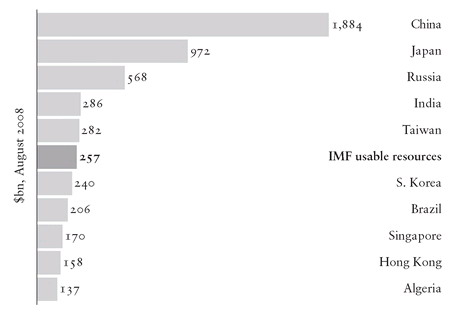

Figure 40. IMF resources and countries with largest foreign exchange reserves.

The American international relations scholar G. John Ikenberry has argued that because the ‘Western-centred system… is open, integrated, and rule-based, with wide and deep foundations’, ‘it is hard to overturn and easy to join’: [1223] in other words, it is far more resilient and adaptable than previous systems and therefore is likely to be reformed from within rather than replaced. This is possible, but perhaps more likely is a twin-track process: first, the gradual but reluctant and inadequate reform of existing Western-centric institutions in the face of the challenge from China and others; and second, in the longer term, the creation of new institutions sponsored and supported by China but also embracing other rising countries such as India and Brazil. As an illustration of reform from within, in June 2008 Justin Lin Yifu became the first Chinese chief economist at the World Bank, a position which previously had been the exclusive preserve of Americans and Europeans. [1224] In the long term, though, China is likely to operate both within and outside the existing international system, seeking to transform that system while at the same time, in effect, sponsoring a new China-centric international system which will exist alongside the present system and probably slowly begin to usurp it. The United States will bitterly resist the decline of an international system from which it benefits so much: as a consequence, any transition will inevitably be tense and conflictual. [1225] Just as during the interwar period British hegemony gave way to competing sterling, dollar and franc areas, American hegemony may also be replaced, in the first instance, at least, by competing regional spheres of influence. It is possible to imagine, as the balance of power begins to shift decisively in China ’s favour, a potential division of the world into American and Chinese spheres of influence, with East Asia and Africa, for example, coming under Chinese tutelage, and forming part of a renminbi area, while Europe and the Middle East remain under the American umbrella. In the longer run, though, such arrangements are unlikely to be stable in a world which has become so integrated. [1226]

11. When China Rules the World

I want to ponder what the world might be like in twenty, or even fifty, years’ time. The future, of course, is unknowable but in this chapter I will try to tease out what it might look like. Such an approach is naturally speculative, resting on assumptions that might prove to be wrong. Most fundamentally of all, I am assuming that China ’s rise is not derailed. China ’s economic growth will certainly decline within the time-frame of two decades, perhaps one, let alone a much longer period. It is also likely that within any of the longer time-frames there will be profound political changes in China, perhaps involving either the end of Communist rule or a major metamorphosis in its character. None of these eventualities, however, would necessarily undermine the argument that underpins this chapter, that China, with continuing economic growth (albeit at a reduced rate), is destined to become one of the two major global powers and ultimately the major global power. What would demolish it is if, for some reason, China implodes in a twenty-first-century version of the intermittent bouts of introspection and instability that have punctuated Chinese history. This does not seem likely, but, given that China ’s unity has been under siege for over half of its 2,000-year life, this eventuality certainly cannot be excluded.

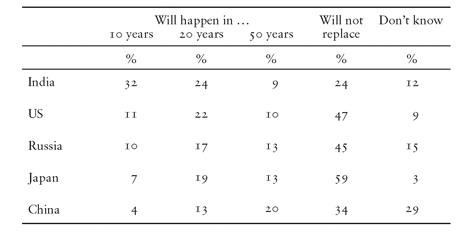

The scenario on which this chapter rests, then, is that China continues to grow stronger and ultimately emerges over the next half-century, or rather less in many respects, as the world’s leading power. There is already a widespread global expectation that this may well happen. As can be seen from Table 6, a majority of Indians, for example, believe that China will replace the United States as the dominant power within the next twenty years, while almost as many Americans and Russians believe in this scenario as think the contrary.

Table 6. Opinions on if and when China will replace the USA as the dominant world power.

There is a well-nigh global consensus that the Chinese economy will one day be as large as that of the United States, if not larger (see Figure 41). Furthermore, as can be seen from Figure 42, this is regarded, on balance, with a surprising degree of equanimity. In a widely cited report published in 2007, Goldman Sachs projected that China’s GDP, in terms of US dollars, will overtake that of the United States in 2027 to become the world’s largest. [1227] These predictions find reflection amongst the Chinese themselves in the extraordinary optimism that they display about the future, greater than that of any other people, Americans included, and which is obviously based on the transformation in their living standards over the past three decades (see Table 7).

As China begins to emerge as a global power, what forms will its growing strength take? Or, to put it another way, what will a globally hegemonic China look like? How will its power be expressed and how will it behave in such a scenario? As we peer into the future, history can in a limited way serve as some kind of guide. Over the last two centuries, there have been two globally dominant powers: Britain between 1850 and 1914, and the United States from 1945 to the present. Given that it is the more contemporary example, the American experience, while in no sense acting as a model, can nonetheless serve as a reference point in seeking to understand what a Pax Sinica might be like, including how it might be different. So what are the characteristics of America ’s global hegemony?

• It has the world’s largest economy.

• It has one of the world’s highest GDPs per head.

• It has the world’s most technologically advanced economy and also the most innovative, as exemplified by Silicon Valley.

• It is by far the world’s strongest military power, which, based on its maritime and air strength, enables it to exercise its influence in every region of the world.

• Its overall global power means that it is a key factor in the calculations and attitudes of more or less every country in the world. All countries, as a consequence, enjoy, in varying degrees, limited sovereignty, from the UK and Israel to Mexico and even China.

• The international economic system was predominantly designed and shaped by the United States and its rules are still determined largely by the US.

• It is home to the best universities in the world and has long attracted some of the most able global talent.

• English has become the global lingua franca largely because of the power and appeal of the United States.

• Hollywood dominates the global film market and, to a rather lesser extent, that of television as well.

• American corporate brand names like Google, Microsoft, Coca-Cola and Wal-Mart tend to predominate over those of other nations. [1228]

• The United States is not only by far the most important country in the world but New York is also, de facto, the world’s capital. What is American also frequently tends to have a global presence.

[1223] G. John Ikenberry, ‘The Rise of China and the Future of the West: Can the Liberal System Survive?’, Foreign Affairs, January/February 2008, p. 1 (available at www.foreignaffairs.org).

[1224] Martin Jacques, ‘The Citadels of the Global Economy are Yielding to China ’s Battering Ram’, Guardian, 23 April 2008.

[1225] Yu Yongding, ‘The Evolving Exchange Rate Regimes in East Asia ’, unpublished paper, 12 March 2005, p. 9.

[1227] Dominic Wilson and Anna Stupnytska, ‘The N-11: More Than an Acronym’, Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper, 153 (28 March 2007), p. 8. This followed an earlier paper in 2003 which suggested 2041; Dominic Wilson and Roopa Purushothaman, ‘Dreaming with BRICs: The Path to 2050’, Goldman Sachs Global Economics Paper 99 (2003), p. 10.