• American history has become part of the global furniture, with its most important landmarks, such as the Declaration of Independence, the Civil War and the frontier spirit, familiar to the entire world. Similarly, its customs, from Thanksgiving Day to Halloween, often have a global resonance.

• American values — be it individualism, democracy, human rights, neo-liberalism, neo-conservatism, the market, freedom or the frontier mentality — often enjoy a preponderant global influence.

• American supremacy has been associated with the global dominance of the white race and, by implication, the subordination and subjugation of other races in an informal global hierarchy of race.

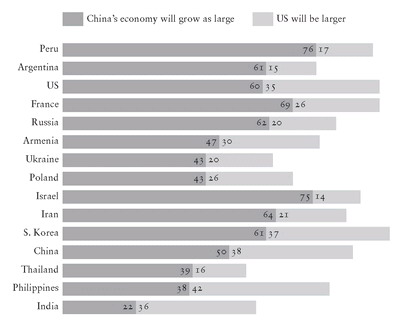

Figure 41. Responses to the question, ‘Do you think that it is more likely that someday China’s economy will grow to be as large as the US economy or that the US economy will always stay larger than China’s?’

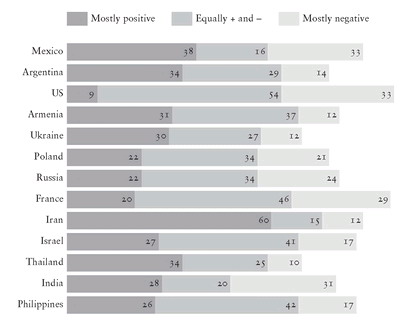

Figure 42. Responses to the question, ‘If China’s economy were to grow to be as large as the US economy, do you think that would be mostly positive, mostly negative, or equally positive and negative?’

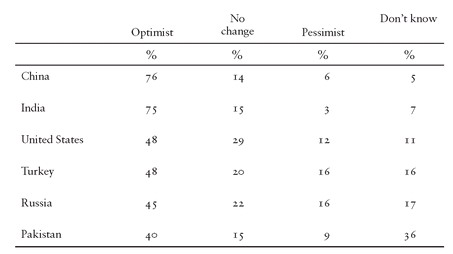

Table 7. Personal optimism (Nov 2005).

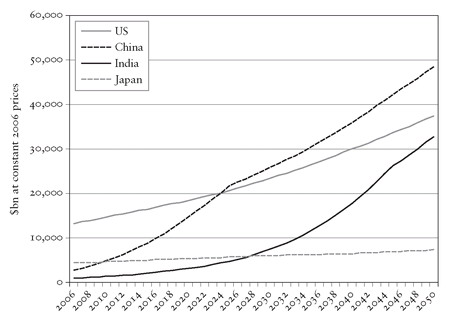

Figure 43. Projected size of major economies, 2006–2050 (GDP at market exchange rates).

Even in the case of the United States, however, whose influence is far greater than that of any other nation in history, this overweening power has never been without constraint. The concept of hegemony elaborated by the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci — which should be distinguished from the pejorative Chinese use of the term [1229] — entails the complex interaction of coercion and consent, force and leadership, and, though it was originally advanced to explain the nature of power within societies, it is also relevant to international relations. [1230] Gramsci’s idea bears some resemblance to the distinction between hard and soft power employed by the American writer Joseph Nye, though Nye’s appoach is less conceptual and more classifica tory in nature. [1231] Far from hegemony being set in concrete, it is constantly contested and redefined, the balance of power never static, always in motion. Nor is it ever absolute. Even though the United States possesses almost as much military firepower as the rest of the world put together, that does not mean that it can do whatever it likes wherever it chooses, as its disastrous occupation of Iraq illustrated. Moreover, as we have observed, while it enjoys military supremacy, its economic preponderance is steadily being eroded. Although the US is the world’s sole politico-military superpower, its influence varies from sphere to sphere and region to region — and in some cases it remains extremely limited. Take the unlikely example of sport. Although the US generally tops the medals tables in the Olympic Games, there are many sports in which it is not dominant and others from which it is virtually absent. The most popular American sports have remained largely confined to the US in their appeal, with the exception of basketball, while the world’s most popular game is football, a European export. Similarly, apart from its domination of a key sector of the fast-food market, American cuisine enjoys little or no global influence.

So what about China? As in the case of the United States, Chinese global hegemony will reflect the country’s particular characteristics, both historical and contemporary. The task here is to identify those characteristics and how they might leave their imprint on the future. It should also be borne in mind that forms of hegemony are constantly shifting and mutating in response to wider cultural, technological, military, political and economic changes. In the era of European supremacy, for example, the characteristic form of political domination was colonialism and the key expression of force-projection was the navy, but after 1945 colonialism, for a variety of reasons, became unsustainable. The American era, in contrast, is associated with air power, a global network of military bases, huge military superiority, an informal empire, dominance of the international economic system, and a global media. It is impossible, beyond a point, to anticipate the new forms of modernity with which a future Chinese hegemony might be associated.

THE LONG REACH OF CHINESE HISTORY

Global history has hitherto been essentially a Western history. With the rise of China, however, that will no longer be the case. Chinese history will become familiar not just to the Chinese, or even East Asians, but to the entire world. Just as many around the globe are conversant with major events in American history (the same also being true of decisive episodes in European history — such as the French Revolution, the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution and the Renaissance — as a consequence of Europe ’s earlier supremacy), so key landmarks in Chinese history will similarly become global property. This process is already under way, as the huge interest that surrounded the Terracotta Army exhibition at the British Museum in 2007-8 illustrated. Of course, the grandeur and richness of Chinese history means that aspects of it, such as the Great Wall, are already quite well known. But this is minor compared with what lies in the future. As an indication, already in 2005 the Great Wall, one of the defining symbols of the Middle Kingdom, attracted more foreign tourists than Florence, the epicentre of Europe ’s Renaissance.

Apart from its extraordinary longevity and bursts of efflorescent invention, the most striking feature of Chinese history is the fact that while Europe, following the fall of the Roman Empire, fragmented into many parts, and ultimately into many nations, China was already moving in exactly the opposite direction and starting to coalesce. It is this unity that has ensured the continuity of its civilization and also provided the size which remains so fundamental to China ’s character and impact. Unity is one of the most fundamental propositions concerning Chinese history, if not the most fundamental. If Europe provided the narrative and concepts that have informed not just Western but world history over the past two centuries, so China may do rather similarly for the next century or so, and thereby furnish the world with an entirely different story and set of concepts: namely the idea of unity rather than fragmentation, that of the civilization-state rather than the nation-state, that of the tributary system rather than the Westphalian system, a distinctive Chinese notion of race, and an organizing political dynamic of centralization/decentralization rather than modernization/conservatism. Given the nodal importance of Chinese unity, the year 211 BC — marking the victory of the Qin, the end of the Warring States period (403–221 BC), and the beginning of modern China — will become as familiar to the world as 1776 or 1789. Qin Shihuang, the first Chinese emperor, who not only bequeathed the Terracotta Army but founded a dynastic system which was to survive until 1911, will become as widely known as Thomas Jefferson or Napoleon Bonaparte, if not much more so.

[1229] William A. Callahan, Contingent States: Greater China and Transnational Relations (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2004), pp. 158- 9.

[1230] Antonio Gramsci, Selections from the Prison Notebooks (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1971), pp. 12–13, 206-8, 333, 416-18.

[1231] Joseph S. Nye Jr, Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics (New York: Public Affairs, 2004), Chapter 1.