11

I LOOKED FOR AN HOUR for a certain file in my office and couldn't find it. I found many things that I should have acted on a long time ago and have not. I found nice letters- unanswered letters, which cause searing guilt beyond all imagining. Also bound galleys of books of poetry from editors hoping for a blurb. Unread and unacknowledged. These bring less guilt, but some, because how hard would it have been to write the editor and explain?

I didn't find the file I was looking for, which holds the drafts of my flying spoon poems. These have swerved in and out of my life for so many years now that I have quite a fat file. The file now stands for the reality. I thought, If I don't find this spoon file I won't be able to write the poem that I was put on this earth to write and my life will have been in vain.

I sprawled in bed grieving for the loss of this file, although I knew it wasn't lost but was somewhere in my office. And then I saw that the only chance I had of writing a half-decent spoon poem was in not finding the file. As soon as I had the file in hand it would smother any new upwellings I might have. I felt released from a heavy burden and I lay in bed blinking at my good fortune. Then my eye moved in a great arc across the ceiling and down the wall across the room. I saw a pile of books that I'd forgotten about, stacked leaningly under a table next to a bookcase. At the bottom of this pile was a folder about an inch thick. I knew from the familiar position of the blue Post-it notes projecting from it that it was the spoon file.

I drove to the John Greenleaf Whittier house in Haverhill, Massachusetts, and joined the tour.

WHITTIER WAS A NINETEENTH-CENTURY POET who wrote a once-famous four-beater about a blizzard, called "Snow-Bound."

On the tour, I sat down in a rocking chair that Whittier sat in. I saw the minuscule stock of books he had in the house when he was a boy, and the poem he wrote about them. It was the tour guide's last day, and she gave our little group-a family of three, a silent woman, and me-her best shot. She brought out the funny bits and the sad bits and showed us the china and the linen and told us about the yarn weasel in the guest room. You crank this weasel to measure out how much yarn you've spun-it keeps track by counting the number of clicks it makes, one click for a certain number of crankings. Hence "Pop Goes the Weasel," a poem with interesting nineteenth-century off-rhymes-"needle," "weasel"-and a surprising number of verses, because you recited it while cranking, and I guess there was a lot of yarn to measure.

Most of Whittier's poetry wasn't good, the tour guide told us. It was tedious, often, and there was too much of it. But his life was good. He'd spent eighteen years writing and editing antislavery newspapers. Once the office of a newspaper in Philadelphia was stormed by a proslavery mob. Whittier, who was the editor of the paper, stole away and put on a wig and a different outfit and joined the looters in the building. They reached his office, calling, Where's Whittier? Where's that whoreson slimedog Whittier? He broke into his office with them and was able to loot his own papers to safety before they set fire to the building. It was after the Civil War that he wrote "Snow-Bound." Which is extremely long, but has several good moments.

The tour guide almost got tearful at the end of the tour, while she sold me a postcard of the room we stood in. Her Ford Mustang was for sale, parked on the grass. She was going west to work for the State of Kentucky.

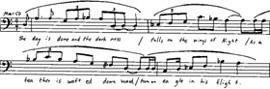

I DROVE HOME from the Whittier house, and as I drove I thought about Whittier versus Longfellow. The two American G-rated graybeards. Longfellow was the greater poet, of course. A strange sad man who lost two wives and a child. He wrote a good poem called "The Day Is Done." Here's its first stanza. I came up with a tune for it:

Hear those mixed rhythms? That poem was the preface to an anthology Longfellow published in 1848, called The Waif. The anthology drove Edgar Allan Poe mad with grief and rage and spite. Why? Because it was a fancy, expensive Christmas present of a book, a book of the North, and Longfellow hadn't included any of Poe's own poems. Poe had written Longfellow fan letters-and then he was left out of The Waif. Left out on purpose, Poe believed. And Poe was right. In his review of the anthology, Poe said that Longfellow had deliberately omitted the American writers he owed so much to. And then Poe went on a crusade, charging Longfellow with theft, writing pseudonymous letters. Longfellow's rejection had pushed him over the edge.

And yet it was all for the best, perhaps. Out of those feelings of miserable exclusion and persecution and lucklessness, Poe wrote "The Raven."

I got home and sat in the kitchen staring at an empty bowl. Paul Chowder's bowl of poetry.

WHAT I'M STARTING to realize is that I don't want a bowl of poetry. I want, more than anything, a bowl of cold potato salad with bits of parsley in there and the skins of the potato and the flesh of the potato but somewhat confused by the presence of the mayonnaise. I want to own a summer-sized drum of mayonnaise. Roz always used to buy a double-big jar of Hellmann's mayonnaise to celebrate summer. I want there to be cold potato salad in the empty bowl. Roz's potatoes held the cold of the fridge inside them, like chewable ice cubes. But there isn't any potato salad.

The mouse came out about ten-thirty p.m. I was still sitting at the kitchen table and I heard a tiny rattle and I saw him climb into the box made of squashed pulp that held the last stalk of blueberries. I'd picked one bunch of unripe blueberries on their stems in order to remember the different colors they have before they turn smoky blue. There are pale greens and pale pinks-Rubensesque colors that you don't expect blueberries to have because you think of blueberries as these smoky heavy bosomy black things in leaf shadow waiting to be plucked. But they're very light and green and springlike in their unripeness. And then they ripen and turn blue-black and finally go all wrinkly and raisinous. The mouse emerged from the stove and did his funny jerky rushing worried progress, branching here and there, retreating, advancing, and finally he made it across past the baking-soda box and the detergent bottle and up on the splash guard, and then he went down into the sink, and up from there into the drainer, and then he climbed into the pulp box and found the bunch of blueberries inside, and he dragged it back up into the stove.

When he came out again I tried to catch him with a plastic pitcher, but he climbed up the curtain and ran along the curtain rod and got away.

Here's the tune I made up for Poe's "Raven." It goes:

Raymond helped me disassemble the bed in Nan's guest room and move it out, and I went to Home Depot and strapped several hundred dollars' worth of pine planks to the roof rack. I bought a new saw blade, and flooring nails with long spirals graven into them so that they'd grip the subfloor better. I felt full of joyful purpose. A floor is a permanent thing. I was putting in a floor for my neighbor Nanette, and getting paid for it.

My finger bothered me a little bit when I was getting a nail started, till I learned to hold it a different way, the way somebody-maybe William Holden-smoked a cigarette. Raymond turned out to have a knack for carpentry. As did Nan, in fact. The three of us stapled down a layer of blue sheeting over the subfloor, and Nan cut around the edge with a retractable knife as if cutting off the excess of a piecrust. Then the planks started going in. We nailed all afternoon. We drank lemonade and talked about zombie movies, and zombie novels, and zombies in video games, and then we nailed some more. Raymond got his music player going, and we sang "Zombie Jamboree." I pointed out the off-rhyme in the song: "belly to belly" and "stone dead already." They were mildly interested. I also made a few mistakes of measurement that Nan saved me from. She had a good spatial sense, which carried us successfully through the tricky area around the bathroom door.