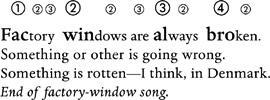

Now what has he got going there? He's got triplets in the first part of the line-"factory windows are"-and doublets in the second part-"always broken."

Bumpada, bumpada, bumpum, bumpum

Bumpada, bumpada, bumpum, bumpum

Factory windows are always broken

Diddle a diddle America

We want to live in America.

It's everywhere.

And sometimes the rhythm isn't a double or a triple, it's a quadruple rhythm. In other words, sixteenth notes, not eighth notes. And sometimes, often in fact, it's a quadruple rhythm made up of an eighth note plus two sixteenth notes that lead you into the next eighth note. That sounds complicated, but when you hear it you'll recognize it as obvious and familiar-something you've been listening to for your whole life. "Death comes with a crawl, or he comes with a pounce," as Edmund Vance Cooke said.

I'm dancing around the barn with my new broom. Dum deem, deedledeem, deedledeem, deedledeem!

WHEN I WAS IN COLLEGE nobody mentioned Vachel Lindsay. Not even a whisper of his name. I heard a lot about Pound and Eliot. We had to read "Prufrock," which is a lovely poem, and "The Waste Land," which is a hodgepodge of glummery and borrowed paste. And I heard about the Spoon River Anthology, and the Black Mountain poets, and Ginsberg and Ferlinghetti, of course, and Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes, and end of story.

But Vachel Lindsay, in his day, was big. He went around doing a kind of vaudeville act using poetry. A one-man minstrel show. He was famous for it.

And one day on one of his tours he came to St. Louis, and there he met Sara Teasdale.

Sara Teasdale was a much better poet than Vachel Lindsay was, and he recognized that, and he fell in love with her and chanted his poems to her and beat his drum for her, and later he dedicated a book to her. And eventually he proposed to her.

She didn't marry him, because basically she saw that he was a lunatic. Very unstable and he had seizures from time to time. But they corresponded for years. And as his fame dimmed and people forgot about him, he got crazier, and he began to threaten his wife-he'd married a young teacher- and he began to have paranoid thoughts that her father was after him. His wife became terrified of him. They had very little money. And when he would go onstage at some provincial women's club, they always wanted him to do his old stuff. "Do the stuff where you bang the drum and sing about Bryant and the Big Black Bucks. Not the new stuff. We don't want the new stuff." And one night back at home he had a fit of rage, and then he calmed down and went down to the basement. His wife called down, "Are you all right, darling?" And he said, "Yes, honey, I'm quite well, thank you-I'll be up shortly."

And then in a little while she heard a sound, blump. And she sat up: something is not right. She rushed downstairs and there was Vachel staggering up from the basement, going erp orp erp. Obviously in extremis. And she said, "Darling, what's happening?"

And he said, "I drank a bottle of Lysol."

Seriously. He died of it, in agony. And it was good that he died because he could feel that he was getting violent. His time was over. He had contributed what he had to contribute. He could sense that. His kind of poetry, which was so performable and so immediately graspable, had fallen out of favor. People like Ezra Pound-who was even crazier than Vachel Lindsay was, and who also, by the way, beat a drum sometimes when he gave readings-were laughing at him. They thought he was a joke. Modernism was winning its battle with rhyme, and he didn't want to be around when Pound and Williams did their victory dance. So he left the scene.

WELL, WHEN SARA TEASDALE found out that Vachel Lindsay had died, she was unhappy, as you can imagine, because in some ways she'd always loved him. She was one of those love-at-a-distance kind of people. She'd loved several men at a distance. And women, too. His death hit her hard, and she was not a healthy woman-she was very very touchy and moody, and sensitive, and hypochondriacal, and a really fine practitioner of the four-beat line.

O shaken flowers, o shimmering trees,

O sunlit white and blue,

Wound me, that I, through endless sleep,

May bear the scar of you.

But she also wrote dirty limericks and then destroyed them. People who read them said they were some of the most incredible dirty limericks they'd ever encountered. Why, why, why did she destroy them? Why? I can hardly bear to think of this loss. Sometimes she suffered from what she called "imeros"-a word from Sappho that meant a kind of almost sexual craving for romance. A lust for love.

One day she hit her head on the ceiling of a taxi while it was driving over a pothole in New York, and afterward she said her brain hurt and she dropped into a funk and eventually she took morphine in the bath and died. And not long after that her friend Orrick Johns-who was also from St. Louis and also a poet, who wrote about the whiteness of plum blossoms at night-he killed himself, too. And later Edna St. Vincent Millay fell down the stairs. So the rhymers all began dying out. All except for Robert Frost. Two vast and trunkless legs of Robert Frost stood in the desert.

I'M NOT A NATURAL RHYMER. This is the great disappointment of my life. I've got a decent metrical ear-let me just say that right out-and some of my early dirty love poems rhymed because I still believed then that I could force them to, and some of those poems were anthologized in a few places. So I got a reputation as a bad-boy formalist. But these days when I try to write rhyming poetry it's terrible. I mean it's just really embarrassing-it sucks. So I write plums. Chopped garbage. I've gotten away with it for years. And I sometimes feel that maybe if I'd been born in a different time-say, 1883-and hadn't been taught haiku and free verse but real poetry, my own rhyming self would have flowered more fully.

But you know, probably not. Probably my brain just isn't arranged properly. Because think: right now we're in a time in which rhyming is going on constantly. All the rhyming in pop music. There's a lust for it. Kids have hundreds of lines of four-stress verses memorized, they just don't call it four-stress verse. They call it "the words to the songs." They call it Coldplay or Green Day or Rickie Lee Jones or the Red Hot Chili Peppers. "Now in the morning I sleep alone, / Sweep the streets I used to own," says Coldplay. "California rest in peace / Simultaneous release," say the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Four-beat lines. Sometimes the rhymes are trite and sometimes not, and it doesn't matter because the music is the main thing. And I'm sure there will be a geniune adept who strides into our midst in five or ten years. The way Frost did. Sat up in the middle of that spring pool, with the weeds and the bugs all over him. He found the water that nobody knew was there. And that will happen again. All the dry rivulets will flow, and everyone will understand that new things were possible all along. And we'll forget almost all of the unrhymers that have been so big a part of the last fifty years. We'll forget about the wacky Charles Olson, for instance, who was once so big. My poems will definitely be forgotten. They are forgettable. They're simply not memorable. Except maybe for one or two. Maybe people will remember part of "How I Keep from Laughing." People seem to remember that one, sometimes. Garrison Keillor read it on the radio once.

NEVER MIND THAT. I soaked my skin graft in saltwater, which wasn't a good idea, but now it's healing nicely. And here's what amazes me. Howard Moss was writing poems at the same time that Allen Ginsberg was. They're so different. Sometimes it's very hard to recapture simultaneity-because even to the people living at the time it didn't feel simultaneous. At the time it felt as if Ginsberg was over here, going "first thought best thought, first thought best thought," and Howard Moss was over here, quietly watching the sun go down through his ice cubes after a day at the office writing a letter accepting a poem sent in by Elizabeth Bishop.