Ginsberg had a poem in The New Yorker, too. In the sixties, Moss accepted one of Ginsberg's poems. It's a good one, too. Very long. It spreads out over parts of two pages. It begins ambitiously: "When I Die." Ginsberg's father, Louis Ginsberg, also had poems in The New Yorker. His poems rhymed and scanned in the old-fashioned way. But his son Allen was smitten by Walt Whitman's preacherly ampersands and he never recovered.

And one day Ginsberg was giving a talk at the Naropa Institute, where he taught, and somebody asked him what the real rhythm of his poetry was. He was in the middle of saying how bad it was for children to be taught traditional meters-the kind his father used-how the bad iambic rhythm warped their little pure Buddha minds. And somebody at the Naropa Institute said, Well then, tell us, Allen. What is the real rhythm of poetry? And Ginsberg replied that the rhythm of poetry was the rhythm of the body. He said that it was, quote, "jacking off under bridges."

And everyone went, Oh ho, chortle, provocative, ho. Because Ginsberg's referring to jacking off under bridges and that's humorous. And it is, frankly. In fact I really like that Ginsberg would say that. It's the kind of refreshing thing that only he and some of the Beats were able to say.

So yes. Except that it isn't true. Because-try it. Just try to imagine standing under a bridge somewhere, holding a copy of Howl. Paperback copy.

You're under a bridge and you're holding your copy of Howl, and you read: "I saw the best minds of my generation zonked out on angry Koolaid in the junky slums of West 83rd street, dah dah dah dah dah dah dah dah-" Help! You can't get anywhere with that. Nobody can.

THE REAL RHYTHM of poetry is a strolling rhythm. Or a dancing rhythm. A gavotte, a minuet, a waltz. Remember those inner quadruplets I mentioned? When each beat is divided into four little pulses? Sixteenth notes, they're called, in music. Not duplets, not triplets, but quadruplets. Tetrasyllables. Some meter people call this the paeonic foot, after Aristotle. There's a useless term for you. But listen to the way they can sound:

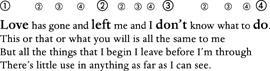

Love has gone and left me and I don't know what to do

That's Edna St. Vincent Millay. Still four beats, but each beat has four inner fuzz-bursts of phonemic energy.

Sara Teasdale did quadruplets, too:

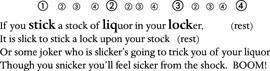

Hear it? People always say that this quadruplet rhythm is for light verse. It doesn't have to be, but it can be. Listen to this four-beater.

That's light verse by Mr. Newman Levy. One of the lesser Algonquinites. Wrote a number of poems about alcohol, as befits a poet of the Prohibition, using that same quadruplet rhythm. Notice there's no rest on the third line, just as in a traditional ballad. W. S. Gilbert, of Gilbert and Sullivan fame, also uses it-"He's a modern major-general." And A. A. Milne:

When the War is over and the sword at last we sheathe,

I'm going to keep a jelly-fish and listen to it breathe.

And Thomas Bailey Aldrich: "And the heavy-branched banana never yields its creamy fruit." Vachel Lindsay used it: "Where is McKinley, that respectable McKinley"-hear the sixteenth notes in "respectable McKinley"? T. S. Eliot used it, under Vachel Lindsay's influence. "Macavity Macavity there's no one like Macavity." Rappers use it a lot-

That's by Ludacris. And Kipling used it a lot, and Poe used it, too. Poe's "Raven," which is probably the best quadruplet rhythm ever written-listen to it slowly:

And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Isn't that smooth?

Four very slow striding beats, with four steady silken swells filling each one. It's so simple and so hypnotic.

And the metrists don't know what to do with it. Here's what one introduction to poetry says. A good introduction by John Frederick Nims. He says that Poe's "Raven" is written in-ready?-"trochaic octameter with lines two and four catalectic." Catalectic meaning cut short. And how far does that get you? It actually disables any understanding of the poem to say that what he's doing is trochaic octameter. Because it's still really a basic four-beat stanza. Poe chose to set it in a different way because the lines came out long, but it's just a ballad. He said so himself. Poe is just taking a certain kind of beautiful stroll. Whether or not he stops under a bridge is not for us to say.

I WENT TO A BEAD STORE in town, and I bought some wire and a clasp and a clamping tool. I've decided to make some of the raw beads I bought for Roz into a real string of beads and give them to her. Not as an aggressive gift, but just as a friendly gift, to thank her for helping me when my finger was bleeding. I've learned to type without using my finger, by the way. Sometimes I type "dinger" for "finger" and "invlude" for "include."

So I went to the bead store in town-Beadle Bailey, it's called. It was very quiet inside. There were thousands of beads in tiny plastic cells, and I was amazed by the choices, the profusion of possibilities. It was like being a poet in that you had indivisible units that you could string together in certain rhythms. You can't alter the nature of a given bead, or a given word, but you can change which bead you choose, and the order in which you string them on their line. And I wanted to string together the beads I chose as a gift, which meant I had a certain person in mind when I looked at the colors. I was looking at the colors with Roz's color sense in my eyeballs. And I had an ideal in mind of rhythm and of randomness. Other beaders were bending, staring into the containers, or looking at the strings of beads hanging from metal hooks on the wall.

I saw some dusty pale small ceramic beads, and I felt the immediate clench of knowing that these were the ones that Roz would like best mixed with the ones I already had from Second Avenue. I asked the beadseller at the register about clasps, and it turns out that you can buy a certain kind of magnetic clasp that frees you from the problem of fitting tiny spring-loaded hooks together. The beadseller put on her reading glasses-she had them on a black-and-yellow beaded string-and she said, "I love these," pointing to one of my selections. She put the singles in a little plastic bag, and the strings, too. The whole purchase went into a pale green paper bag, and I walked out blinking onto the street carrying the raw materials for my present to Roz and feeling a joy of knowing that I was going to make something for her-something like a poem, but better than any poem I could write.

I think I'll do a quadruplet rhythm, a love-has-gone-and-left-me rhythm: one gray-green bead and then three other beads of near-random colors, and then a gray-green bead again.