And here is the original bookmark, from the bookstore where I bought the book. The Grolier book shop in Cambridge. Little poetry shop on a side street off Harvard Square. It's had some tough times recently.

"The Fish" takes up three pages. It's long. It starts here, and it goes over here, and then it goes over to here. And every word on these three pages is worth reading. In her letter to I think it's Marianne Moore, she says that she feels very adventurous because she's not capitalizing the first letter of each line.

The way to read the poem is not to read it in the book, but to listen to her read it on a CD. She has a such a marvelously simple way of delivering it. She just seems to shrug it off her. It's of no interest to her that it's poetry. There's no fancy emphasis. It's almost flat, the way she reports it, and she has a slight midwesternness to her voice. It's so lovely, and she sounds very young and surprised that she's been asked to read it.

You know what "The Fish" is? "The Fish" is sort of like a Talk of the Town piece in The New Yorker if the Talk of the Town had died and gone to heaven. That's what it is, a perfect Talk of the Town piece. Except that it doesn't use the "we." And it didn't appear in The New Yorker-it appeared in Partisan Review. And I don't even care whether it's called a poem or not. It doesn't scan. She was a woman who was very capable of rhyming. Who liked rhyming. But this one is not a rhyming poem.

The Fish! The fish. "I caught a tremendous fish." Here's the situation. Elizabeth Bishop is in a boat, on her own, it seems, and she's caught a tremendous fish, that's come out of the ocean. What does the fish want to do? The fish wants to get back to the water. But she doesn't let it. She examines it very closely. She looks at its peeling skin and compares it to old wallpaper. She repeats the word "wallpaper" twice in two lines of a poem-an unheard-of prosiness. And then she bends closer, and she looks right into the fish's eye. She says it's larger than her eye but shallower. And that's true-we all know those shallow fish eyes. "The irises backed and packed / with tarnished tinfoil." She's really peering at that fish's eye now. And then, whoa: the eye shifts. The fish eye moves. Terror. We know right then for sure that it's alive.

All that careful slow description suddenly has a kind of near panic in it, because we know that the fish is out of its element, breathing in the terrible oxygen. The fish doesn't want to be described. That's what gives the poem its pull. The fish resists description because it just wants to be back in the water, and not to be seen, but she's insisting on looking at it and coming up with one simile after another. All these wonderful similes take time, and meanwhile the fish is starting to suffocate.

So we look at his skin, at his scales, at his swim bladder, which is like a peony, and his eyes. And then, we get to "the mechanism of his jaw." And here's where we learn about the fish's history-the five pieces of broken-off fishing line. And she describes each kind of fishing line. One line is green, and the others are black, and we hear all about them. And those lines are allegorical. They're lines of what? Of poetry. Because we know that other people-other anglers, other hopeful poets-have caught this very same ancient, real fish. Their lines are there, hooked into the fish's jaw, all the many other attempts to rhyme this old fish into poetry. Rupert Brooke has a beautiful poem about this very same fish. But Elizabeth Bishop's hooked it now, and she's not going to rhyme it, she's just going to tell us about it.

And that's what leads her to her last line, when she's there in the boat, and the fish is gasping and-ploosh-"I let the fish go." Because that's what you have to do. You take the moment, you do your best to describe it, it fascinates you, and then when you've done your best to give it to people on some printed page, then you have to let it go.

For the rest of her life, when she was asked to give a reading, they wanted her to read that poem. Till she completely lost track of the reality behind it and didn't want anything to do with it and wished the anthologists would pick something else.

And if you listen to her reading it, you'll notice that there's a tiny moment just after she says "And I let the fish go" before the tape hiss stops. In these old poetry recordings, the audio engineer always pulled the level down too soon, immediately after the last word, without any mental reverb time, and oddly enough it works beautifully. You hear "Ffff, and I let the the fish go, ffff-" and then silence. You're in the empty blankness before the next poem. The black water. The fish is already gone, out of hearing. Even the hiss of the tape, the water in which the fish swam, is gone. You have to return reality to itself after you've struggled to make a poem out of it. Otherwise it's going to die. It needs to breathe in its own world and not be examined too long. She knew that. The fish slips away unrhymed.

I think I'm going to go to RiverRun Books and look at the poetry shelves. When I see new books for sale there that I already own, it makes me happy. It makes me feel that there's part of the world that I really understand.

10

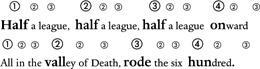

Thomas Edison's people convinced Alfred Tennyson to chant the "Charge of the Light Brigade" into a microphone. You can hear it in a BBC collection, and you can hear it in a CD that comes with a book called The Voice of the Poet. Tennyson sounds like this:

pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff! pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff!

pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff! pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff!

Hobble leg, hobble leg,

hobble leg owhmmm!

Into the bottle of fluff, rubbed the stuff under!

pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff! pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff!

pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff! pkkkffffffrrrffff-fff!

But under the static of the wax cylinder, did you hear what Lord Alfred was up to? He was using the regular four-beat line, but he was using triplets within each beat. One-two-three, one-two-three:

That's how he reads it, with the triplets. Triplets are called dactyls or anapests in the official lingo, depending on whether they start with an upbeat or not. But those words are bits of twisted dead scholarship, and you should forget them immediately. Put them right out of your head. Wave them away. The poetry here is made up of triplets.

Triplets are good for all kinds of emotions. People think they're funny-and they are. They work in light verse and in limericks. "There was a young man from North Feany-rest. Who sprinkled some gin on his weenie-rest." Dr. Seuss uses them: "A yawn is quite catching, you see, like a cough." Ya-ta-ta, ta-ta-ta, ta-ta-ta, tum. Light.

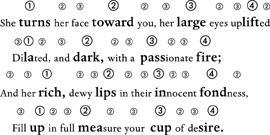

Or you can use them for a love scene:

That's by Mary Louise Ritter, a forgotten poet, out of an old anthology called Everybody's Book of Short Poems, which once sold thousands of copies.

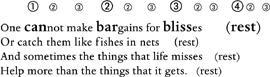

Or you can use triplets to dispense advice:

That's a poem by Alice Carey that was very big a century ago. If you read it aloud, you might feel yourself declaiming it too bouncily. But if you sing it, you'll find that you slow down and you begin to hear the wisdom in what she's saying:

James Fenton-who is the best living love poet-uses this same triplet rhythm, with the same end-rest on a four-beat line and the same warningness: "It's something you say at your peril (rest) / It's something you shouldn't contain (rest)."

And you can mix triplets together with duplets. Swinburne was the great rhythmic mixmaster, and before him Christina Rossetti. And Vachel Lindsay was good at it, too. Vachel Lindsay was a chanter and drumbeater. In the twenties, for a short time, he was probably the most famous poet in the U.S.A. Listen to what he does.