The gathering was called the Global Word Congress, and the air was so thin at that altitude that you had to stop every so often to catch your breath, and it changed the way you thought after a while. Some of the poets were being paid to be there. Most of them were paying to be there. We all slept in the ski lodges.

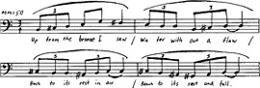

On the second day was the panel discussion with Renee Parker Task and two other people on "The Meters of Love." Renee was brilliant and distant and wise; my enraging blushing tongue-tiedness kicked in early as I knew it would, and I went all silent and shifty. I made an unnatural snort of a laugh when Renee mentioned "the pentameter line." Then I thought, Pull yourself together, you cairn of burning garbage, you're not going to get many more chances like this. So I talked about scansion and enjambment and the importance of the invisible rest, and I said that pentameter was really a waltz, and I talked about how some enjambments made Louise Bogan shudder and rightly so, and then something strange came over me and I opened my mouth and out of it came the tune I'd made up for the first stanza of Bogan's "Roman Fountain."

Afterward a woman from New York came up and asked me what the name was of the poem about the fountain and I told her. She said, "'Rush to its rest' is really nice," and I nodded, and I thought I'd at least done something good in offering them some Louise Bogan.

THE MASTER CLASS I gave had a rocky moment. I told them to copy poems out, and to start by saying what they actually wanted to say, and to read their drafts aloud in foreign accents, and to clean out their offices, and to make two supporting columns when they packed their books in a box, and I described trying to edit an anthology and how crazy it made me, and I heard myself sounding more or less like a professional poet. Which amazed me.

And then a man of forty or so, with a French accent, asked, "How do you achieve the presence of mind to initiate the writing of a poem?" And something cracked open in me, and I finally stopped hoarding and told them my most useful secret. The only secret that has helped me consistently over all the years that I've written. I said, "Well, I'll tell you how. I ask a simple question. I ask myself: What was the very best moment of your day?" The wonder of it was, I told them, that this one question could lift out from my life exactly what I will want to write a poem about. Something that I hadn't known was important will leap up and hover there in front of me, saying I am-I am the best moment of the day. I noticed two people were writing down what I was saying. Often, I went on, it's a moment when you're waiting for someone, or you're driving somewhere, or maybe you're just walking diagonally across a parking lot and you're admiring the oil stains and the dribbled tar patterns. One time it was when I was driving past a certain house that was screaming with sun-litness on its white clapboards, and then I plunged through tree shadows that splashed and splayed over the windshield. I thought, Ah, of course-I'd forgotten. You, windshield shadows, you are the best moment of the day. "And that's my secret, such as it is," I said.

They all looked at me, and I looked at them. I was the teacher. I was the authority. And then I said, "Of course, it hasn't worked all that well for me. My first book was okay. But you know what Amy Lowell said. She said, 'Poetry is a young man's job.' " And then I burst into tears.

No wonder they call it bursting. It's a sudden outflipping of the lips and an explosion of liquid from behind the eyelids. Everything that's inside is suddenly coming out. It's really a physical event. You're literally shaking with sobs. Fortunately it didn't last too long.

I apologized and sniffed and smeared my fists in my eyes and collected myself. Then I cleared my throat and I said, more formally, "That's about all I have." The class broke for buffet supper in the Rimbaud Room.

I STARTED UP a path toward one of the mountain cable-ways. There were hundreds of ideally spaced dandelions on sharply tilting fields, and there was a remote clink of sheep bells, which are similar to cowbells. It seems that sheep farming receives government subsidies in Switzerland so that the clink will continue. And on every path were more wandering poets. You turned a corner and there was another out-of-breath, sweaty, wandering poet. Some had little notebooks, some had cameras, some held a precious paperback. I saw a little red-haired man in a velvet jacket carrying Charles Simic's poems-the edition with the beautifully empty paper bag on it. I said, "Algernon?" He shook his head. I said, "Oh, sorry."

I kept climbing, and then I stopped and sat on a bench and looked across a valley at a distant triangular mountain. The mountain was white, because it was covered with snow, and it looked almost flat-perhaps a trick of the rarefied air. I sat and thought about having a crying jag in my own master class, and then I noticed that the mountain was doing something unusual: it was reflecting quite a lot of white light toward the shadowy mountain that we poets were on. It sent its sideways light deep into the underbranches of the woods, and it made the sedums grow there with unnatural vigor. The sedums were growing in reflected Swiss mountain snowlight. And that was the best moment of the day.

Later a woman told me that when she took LSD she thought she could unscrew her breasts and hand them out to people to use as drinking bowls.

I kept my word to Roz and didn't have an affair, which wasn't too difficult because there was no possibility of it.

17

I WROTE TWENTY-THREE POEMS on the plane back from Switzerland. I always write lots of poems on airplanes, but this was a personal best. When I got home, I saw that Nan's son, Raymond, had piled my mail neatly on the kitchen table. I stared for a long time into my dry beautiful sink. The disposal said "IN-SINK-ERATOR." I'd never read my own disposal before.

Then I sat down at the kitchen table for three days and I put together a clean draft of the introduction to Only Rhyme and sent it off to Gene. I wore the same shirt the whole time so as not to lose momentum. The introduction explains things, but clumsily. Everything is much quieter and more filled with exceptions than how I've presented it. But at least there are things I've said that I know are true. I'm happy about that. It's two hundred and thirty pages long.

I called Roz and told her I'd written twenty-three poems and the introduction to Only Rhyme and would she move back in with me. She called back and said she didn't want to move back in-that she'd spent a lot of money at IKEA and gotten her place the way she wanted it, so not right now. But did I want to come over for dinner on Saturday? I said yes, I did, I very much did.

I'M WORKING for Victor now, painting houses. Or "Vick," as he likes to be called. Much much better than teaching. Painting houses inside and out, jabbing the brush into corners and clapboard seams. It helps me think. I'm up on an aluminum ladder for real. Being paid for my work. The first evening of Vick's poetry series is going to be devoted to Sara Teasdale. I sent a letter to Mary Oliver inviting her to come up. I doubt she will, but it's fun to invite her.

I wonder what it must be like to be part of something ongoingly huge like a number-one sitcom or part of a magazine when it's in its golden moment-like The New Yorker in the thirties-or a fashionable restaurant or a hit musical. Something that everyone wants to think about at the same time. Some people have that privilege. Most don't. And the ones who do are no more content than I am.

Out of the poems I wrote on the plane, I sent three off to this year's TLS poetry competition. Alice Quinn and Mick Imlah are the judges. Good old Alice. I know I won't win, but it's like inviting Mary Oliver to our series-a welcome flutter of excitement. And Gene has now read the introduction to Only Rhyme. "We're going to need to make some cuts," he said, but he said it'll do. So I'll get a pale green check from him. I've invited Roz to come over to play badminton, also Nan and Chuck and Raymond. I've taught Smacko not to bite the birdie by hitting it out onto the grass and then rewarding him with a crouton when he doesn't lunge.