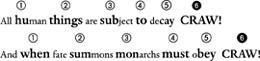

BUT NOW FOR THE REAL THORNINESS: PENTAMETER. "All human things are subject to decay." That's the line. Then: "And when fate summons monarchs must obey." And you think, Okay, good, I see five stresses there, like five blackbirds on a power line.

Five little blackbirds. Ah, but there's a raven of a rest there at the end that you're not counting, my friend. If you say the two lines together, you'll hear the black raven. Listen for him:

If you leave out those raven squawks-those rests-and you only count the blackbirds on the line, you are not going to be able to say this couplet the way Mr. Dryden meant it to be said. Try it as a run-on. "All-human-things-are-subject-to-decay-and-when-fate-summons-" What? Who? Where am I? You see? It's just not right that way. You cannot have five stresses in a line and then jog straight on to the next line. If you do that, it sounds out of whack. It sounds horrible. It sounds like-enjambment.

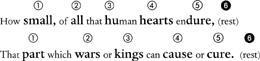

Let's take another example of a heroic couplet. This one is from Samuel Johnson. He wrote it for his impoverished drunken friend Oliver Goldsmith.

You've got to have the rests! There's no question about it. If you don't have the rests, you don't have a proper couplet. These are six-beat lines. So-called iambic pentameter is in its deepest essence a six-beat line.

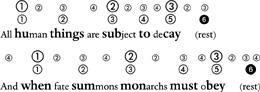

Actually no, I take that back. It's not. In its very deepest, darkest essence it's a three-beat line. Here's where we get to the nub of it. Because people really only hear threes and fours, not sixes. Let's take a look at how this works. And to do it, we're going to up the pace a little bit. We're going to say some of these lines flowingly and fast, listening for the way they truly fall. And as we do, we're going to tap our feet in rhythm. Let's try it. Get your foot tapping with me, in a nice slow walking pace.

With me now: One--two--three. One--two--three. "How small of all that human hearts endure (rest), the part which wars or kings can cause or cure (rest), all human things are subject to decay (rest), and when fate summons monarchs must obey (rest), that time of year thou mayst in me behold (rest), When yellow leaves or none or few do hang (rest), When I have fears that I may cease to be (rest), before my pen has gleaned my teeming brain (rest)." Are you with me? I feel like I'm making an exercise video.

What's happening is that if you tap your foot only to the big beats, you end up with a line of inner quadruplets chugging away in sync with three large stresses. You can chart it like this:

Looks like an air-balloon festival, does it not? But I hope it shows that what we call iambic pentameter is really, if you count the rest the way you must count it, a kind of slow waltz rhythm. You can leap around the room reciting so-called iambic pentameter to yourself and your leaps will fall in threes. You cannot make your leaps fall into fives. You need to add the rest. I'm telling you that this is true. No amount of reading and underlining any textbook about meter and seeing them go on and on about five beats is going to make that necessary sixth rest beat go away. It's there, and it's been there for centuries. And when poets forget that it's there, it hurts their poems.

15

MISTY AGAIN TODAY. A freakish mist lies over the land. My clothes are out on the clothesline, and they have been there for two days and they've started to get that wet-too-long smell.

Now, if I were a nineteenth-century poet, I would say that the freakish mist lay "o'er" the land. And that's one of those words, "o'er," that makes a modern reader feel ill. So what I do, to make the old poems feel true again-the good old poems-is very simple. This is another little tip for you, so get ready. I just pronounce "o'er" as "over," but I do it very fast, so you're gliding o'er the V, not really adding another syllable. Because that's really what it was, I think: it was a crude, printed representation of a subtle spoken elision that might well have had some of the vocal ghost of the V left in it.

There are rare times when it's absolutely necessary to say "o'er" without any V-as when, say, Macaulay rhymes it with "yore." But a lot of the time you can fudge it.

This trick will also work for "'tis" and "ne'er"-the other painful bits of poetic diction. When I'm reading a poem to myself, I just mentally change all the instances of "'tis" to "it's." And I give "ne'er" the "o'er" treatment-I just barely graze my teeth with my lower lip, while thinking V. It's like waving the vermouth bottle over the glass of gin. Try it, it may work for you.

After all, we don't want some mere convention of spelling to block our connection with the oldies. We want to hear them now as if they're being said now. And that tailcoated diction can really get in the way. It's bad. Not to mention the exclamation points everywhere. Lo! Great God! Just ignore them. If you say the poem aloud, they disappear.

The mouse climbed up the curtain again, and this time I got him to drop into the plastic pitcher. I took him out to the lilac bush and let him go in the mist.

I CALLED UP ROZ to ask her if there was anything she wanted from Switzerland. She told me she had the flu and wasn't thinking straight because she had a fever. I asked her if I could bring over some chicken soup and crackers and ginger ale, because I knew that's what she'd want. And she said, "That would be nice. Also some chewable Motrin, the junior kind, and a trashy magazine." So I went over to her apartment, which she'd painted five careful colors-and I helped her sit up. She really had been quite sick, very feverish, hot, confused. "I'm here to take care of you," I said, and I gave her the chewable Motrin and a spoonful of soup, and she ate a corner of a cracker.

"Let me think of cold things to cool you down," I said. "Do you remember how you used to make that marvelously cold potato salad and we'd have it outside on the metal table?"

She nodded. "On cool tin plates," she said. "That was fun." Then she said she was going to sleep, and she thanked me for coming by.

IMOWED more of the lawn. But first I cut away the thorny brambles so that they wouldn't attack me as I mowed near them. What I found was that grapevines were kinking their spirals around the long, reaching, hooky bramble suckers. The two plants had a little gentlemen's agreement going, like the railroad companies and the real-estate speculators in the old days, whereby they progressed together up the hill and into the yard. I pulled some of their tanglement out of an old, beleaguered lilac bush, and I got pricked a lot but I felt I'd accomplished something. Then I mowed for an hour and chanted a stanza of Kipling as I mowed, from his poem about the undersea cables.

The wrecks dissolve about us; (rest)

Their rust drops down from afar- (rest)

Down to the dark, to the utter dark,

Where the blind white sea-snakes are. (rest)

When I was done mowing I drank a glass of iced coffee with some baking soda mixed into it to soften the burn. And I went up to my now half-empty bookcases in the hall and found Theodore Roethke's prose collection, On the Poet and His Craft. It's a small white book. On the cover is a picture of Roethke looking sad, as he always looked, sitting against a wall with a mysterious white graffiti hand-painted on it. The dustjacket is very soft on the top and the bottom edges because it has slid out of place and crunched into things. Holding this book always affects me strangely. It was put together by one of Roethke's colleagues, and it came out only a year or two after Roethke died. It's like standing in some little cemetery somewhere, staring at a small white gravestone in the grass.