Goody for all of them. It's all about a piece of steak. There's that Jack London story, about the old tired boxer who almost wins a comeback, but he doesn't because he didn't have enough money to buy that one piece of steak he hungered for the day before-the steak that would have given him the strength to land the big punch. So he's beaten. He's smacked around. He bleeds. He fails. That's me. If I could only have written a good flying spoon poem back three years ago when I first wanted to, I might be poet laureate right now. Maybe. Probably not. But maybe. I might be going to fancy diplomatic receptions and talking to flirty women from the Spanish embassy with no shoulder straps and eating steamy vulval canapes that leap into my mouth practically of their own volition. I would be part of the Washington evening scene, and I'd be sent invitations to receptions engraved on heavy stationery, with very sharp corners and skimpy tissue overlays that would fall and glide low and long across the floor. I'd own a black-tie outfit. But it has all happened a different way. I'm up here in Portsmouth, city of brick sidewalks. And I like this city a lot. But I'd love those canapes, too.

14

I'VE JUST HAD A SHARP FLARE of an emergency, but I think it's now under control. What happened was I remembered that I should put my passport in my briefcase so I wouldn't forget it when I went to the airport to go to Switzerland.

And then suddenly I wondered: Is my passport possibly out of date? I thought, no, it can't possibly have expired. I looked in my top drawer among the socks and the under-pants and my fragile folded birth certificate, and there it was. I flipped it open with my paperback-holding fingers and looked inside and there was my more-than-ten-years-younger face, and yes: it was expired. My flight is on Monday night, and this was Thursday.

I called the federal government of the United States, and a nice woman who worked there made an appointment for me in Boston on Monday morning at nine-thirty.

YOU SEE, this is what I'm up against. This little book here. Published by Farrar, Straus, which publishes Elizabeth Bishop. It's James Fenton, An Introduction to English Poetry. Very nice indeed. In it he says some true and interesting things and some false things.

We can't blame him for saying the false things, because he's saying what everybody has always said from the abysm of time. First he says that iambic pentameter is preeminent in English poetry. No it is not. No it is not. Iambic pentameter is an import that Geoffrey Chaucer brought in from French verse, and it was unstable from the very beginning because French is a different stress universe than Middle English and it naturally falls into triplets and not doublets. No, the march, the work song, the love lyric, the ballad, the sea chantey, the nursery rhyme, the limerick-those are the preeminent forms, and all those have four beats to them. "Away, haul away, boys, haul away together, / Away, haul away boys, haul away O." Fenton's own best poems use four-beat lines.

And then Fenton says that iambic pentameter is, quote, "a line of five feet, each of which is a ti-tum. As opposed to a tum-ti."

And that's what they all say. Fenton doesn't know what he knows. He's written beautiful iambic pentameter lines. His ear knows that there's more to it than that. And he is just one of an endless line of people who say that an iambic pentameter line is made up of five feet, or five beats. And it isn't. An iambic pentameter line is made up of six feet. Or rather five feet and one empty shoe-i.e., a rest. Unless the line is forcibly enjambed and then, to my ear, it sounds bad. Keats, bless his self-taught genius soul, came up with some scary enjambments. "My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains," next line, "My sense."

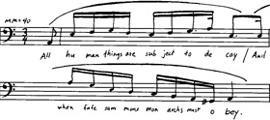

BUT LET'S GET the Sharpie out. And let's take a look at a real iambic pentameter line. Two of them, in fact, from Dryden. I'm going to write them out for you. This is the couplet that I copied out in my notebook, as I think I mentioned. It's called a heroic couplet-and Dryden was the one who really made it work in English. He forced its preeminence. He used it to write what he called "heroic plays," and he used it to translate Virgil's Aeneid, which is about the heroic deeds of gods and men. And after him came Pope and everyone else. The couplet goes like this. I'll sing it.

Now, the way we're taught to talk about these two lines is to say that they are in iambic pentameter. There are two parts to this. First, "iambic." And second, "pentameter."

"Iambic" is a Greek word that in English just means an upbeat. The iambic conductor puffs out his man chest, lifts his batoned hand up, and everybody sees the eighth note hovering there before the bar line on their music stands, and the string tremolo builds, and the mallets of the tympani blur, and the chord swells, and crests, and gets foamy at the ridge, and then the baton comes down and a big green glittering word-wave crashes down on the downbeat. Ya-ploosh. Ka-posh. "All human things." That's the iamb. It's a kind of sneeze. Iambs can begin four-beat lines or so-called pentameter lines, which are really six-beat lines. "Oh who can from this dungeon raise." "A soul enslaved so many ways." "And what is Art whereto we press." "The world is too much with us." "I met a man who wasn't there." Let's see, what are some more? "The wed ding guest, he beat his breast." "My lit tle horse must think it queer." Dang, I keep wanting to use shorter lines as my examples. Which is my point.

But let's see, let's see. "I should have been a pair of ragged claws." Prufrock. Iambic pentameter. "When I have fears that I may cease to be." Keats, iambic pentameter. "Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world." Yeats, iambic pentameter. "And slender hairs cast shadows, though but small." Dyer. "If you can keep your head when all about you." Kipling. "The art of losing isn't hard to master." Elizabeth Bishop. "They flee from me who sometime did me seek." Et cetera, et cetera. "Et cetera" is an iambic rhythm, if you pronounce it the way the French do. And iambs are extremely common. The first syllable is an upbeat to the line, and the rhythm is a game of tennis-it's that basic duple rhythm, badoom, badoom, badoom.

Now one problem with "iamb" as a name for this clearly audible upbeat phenomenon is that the word "iamb" isn't iambic, it's trochaic. A trochee is a flipped iamb. It's like a staple-crunch: crunk-unk. "Iamb" is trochaic. Isn't that the most ridiculous thing you ever heard? And we've tolerated and taught this impossible Greek terminology for centuries. If iamb were pronounced "I am!"-as a counterfactual-it would itself be iambic. "I am interested in what you're saying!" "I am going to take out the garbage!" "I think therefore I am!" You hear that? Then "iamb" would be a decent name for what's going on. Not a great name, but a decent name. But no, it isn't pronounced with the stress on the second syllable. And yet this is what we've got to work with. "Iambic" is the name for this sort of upbeat when it's found in a duple rhythm. Not in a triple rhythm. In a triple rhythm, there's another Greek word you can use, if you're inclined: "anapest." But in a double rhythm, a line that begins with an upbeat is iambic. If you follow me. Just saying all this creates a fog of brain damage.

But so much for the first part of the phrase, "iambic." Just set it and forget it. Don't worry about it. You can change an initial trochee to an iamb by adding an "And" or an "O." And you can flip around an iamb so that the line begins with a little triplet, or an eighth note and a sixteenth note, which happens a lot-as in "Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness." Or "Give me my scallop-shell of quiet." So the whole notion is fluid, and we don't need to dwell on it any longer. Some lines begin with an upbeat and some don't-that's all you need to know about the iamb.