* * *

The president’s voice is strong and clear.

“We Americans of today, together with our allies, are passing through a period of supreme test. It is a test of our courage, of our resolve, of our wisdom, of our essential democracy,” Roosevelt tells the nation.

As he looks out on the crowd standing below him on the South Lawn, he does not make eye contact with anyone in that sea of overcoats, scarves, and fedoras. Indeed, he does not make any attempt to recognize them at all. The president’s gaze remains fixed on a line of trees in the far distance. His thoughts are focused on the microphone before him, knowing that his pitch-perfect vocal delivery will have far more impact on the millions listening on the radio.

“Our constitution of 1787 was not a perfect instrument; it is not perfect yet. But it provided a firm base upon which all manner of men, of all races and colors and creeds, could build our solid structure of democracy.

“And so today, in this year of war, 1945, we have learned lessons—at a fearful cost—and we shall profit by them.

“We have learned that we cannot live alone, at peace; that our own well-being is dependent on the well-being of other nations far away. We have learned that we must live as men, not as ostriches, nor as dogs in the manger.

“We can gain no lasting peace if we approach it with suspicion and mistrust or with fear. We can gain it only if we proceed with the understanding, the confidence, and the courage which flow from conviction.”

After a few final sentences invoking the blessing of the Almighty, Franklin Delano Roosevelt concludes his fourth inaugural address. It is just 558 words long—only George Washington’s second inaugural was shorter. Fifteen minutes after the ceremony began, it is over.

The crowd files back out of the White House grounds without commotion or celebration. They have achieved their goal: they have seen history made.

Harry Truman returns to his office in the Senate Building and begins cleaning out his desk.

And Franklin Delano Roosevelt turns his attention to an event even more pivotal than his inauguration: next week’s meeting with Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin to determine the fate of Nazi Germany.

It will take place in a seaside Soviet resort town known as Yalta.

14

AUSCHWITZ-BIRKENAU1

OŚWIĘCIM, POLAND

JANUARY 26, 1945

1:00 A.M.

The earth convulses as Krema V explodes. Tongues of flame turn the coal-black winter sky a bright red. Nazi SS guards watch the inferno intently, but only for as long as it takes to know that the destruction is complete, and there will be no need to place another round of dynamite charges. The grisly evidence is now destroyed.

The guards march to the nearby barracks and order the prisoners out into the snow. The skeletal children with their prison tattoos and shaved heads respond immediately, knowing that the punishment for being too slow is a bullet. The prisoners get in line. The SS guards are normally fond of neat, military-style rows, which allow them to take a head count. But on this night they are in a hurry.

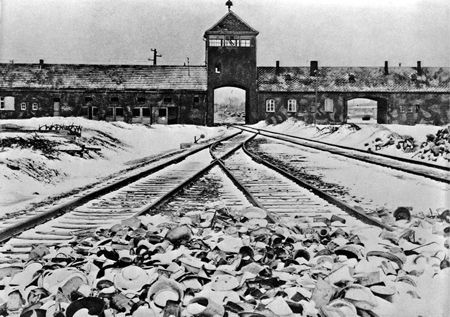

The prisoners are ordered to march. Their destination is unclear, but the road soon takes them past the train station where they first entered this hellhole, and then on by the commandant’s lavish house. They are leaving Birkenau, though they know not why.

The entrance to Auschwitz

Their way is lit by the burning remains of Krema V. That horrible redbrick building where hundreds of thousands of their fellow prisoners entered, but where none walked out. Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and the handicapped were led inside, locked in an airtight room, and then gassed when a cyanide-based pesticide known as Zyklon B2 was dropped through the ventilation system. Death came slowly as the prisoners, unable to breathe, tried to claw their way out of the room, leaving scratch marks on the walls.

The bodies were then burned inside special ovens, with ashes going up the chimney flu, where they belched forth into the Polish sky and floated to the ground like snow, covering the nearby forests, ponds, and fields. The smell of death dominated the land.

But Krema V is no more. The other four Auschwitz crematoria have also been detonated. Adolf Hitler has ordered that the murders be stopped and that all proof of his atrocities be destroyed. Though taking heavy losses, the Soviet army has blown through the German defenses in Czechoslovakia and Hungary, and is rapidly advancing west. To the north, the Russians have captured Warsaw, and are racing through Poland with the intent of occupying Berlin before the Americans and their Allies can get there. The Russians are so close to Auschwitz that the boom of their artillery can be heard in the distance, and the occasional barrel flash of a launching shell limns the horizon. The SS guards who have been ordered to destroy the crematoria are eager to move on, or they will soon become Russian prisoners—a certain death sentence for them.

But even now, when their thoughts are filled with plans to escape, the SS cannot stop themselves from killing. It has become a way of life for them over the past few years, as routine as eating breakfast. They have shot thousands by lining them up against the notorious “Black Wall,” as the firing squad barrier next to the medical experiments barracks is known. Now, as the SS men prod the prisoners through the snow, moving them to another section of the concentration camp on a road lined with electrified barbwire fences, those child prisoners unwilling or unable to walk the mile from the Birkenau section of the death camp3 to the main section of Auschwitz are immediately shot dead.

Those who bend down to quench their thirst by scooping snow into their mouths are shot dead.

Many of the children now marching through the snow are twins who have been the subject of cruel experiments by a madman named Dr. Josef Mengele.4 Those who stop to help their twins are also shot dead.

Ten-year-old Eva Mozes and her twin sister, Miriam, stumble through the snow. As veterans of Mengele’s experiments, their bodies are shattered. The “Angel of Death” showed them just one act of kindness, allowing them to keep their hair. The wind cuts through the thin prison uniforms the girls wear. Eva and Miriam’s toes tingle and then go numb in their loose-fitting clogs. They have been in Auschwitz for a year. They were the only Jews in their hometown of Portz, Romania, and until 1944 no one seemed to pay much attention to them. But then the Nazis forced them to move out of their home and into a Jewish ghetto to await transport to Auschwitz.

The memory of their arrival is still seared into Eva’s brain. After a seventy-hour ride from the Jewish ghetto in Şimleu Silvaniei, they stepped off the cattle cars. Guards5 yelled “Schnell, schnell”—“Quickly, quickly!”—as dog handlers allowed their snarling animals to lunge at the new arrivals.

The twins’ father, Alexander, and two older sisters, Edit and Aliz, were immediately separated from the rest of the family.

Jaffa, the girls’ mother, sought to protect her young daughters. She grasped each one tightly by the hand. But a quick-thinking guard immediately noticed the twins. That’s what they’d been trained to do: find twins and dwarves. With a gleam in his eye, that guard took the two girls to the special children’s barracks reserved for the patients of Dr. Mengele. Eva and Miriam screamed at the top of their lungs, crying and pleading as Jaffa was torn from them, soon to be gassed and burned. They never saw her again.

At age ten, the girls were completely on their own. Nevertheless, they were determined to live. “The first time I went to use the latrine located at the end of the children’s barracks, I was greeted by the scattered corpses of several children lying on the ground,” Eva will later remember. “It was there that I made a silent pledge—a vow to make sure that Miriam and I didn’t end up on that filthy floor.”