“Now the enemy must dance to our tune, not we to his.”

13

WHITE HOUSE

WASHINGTON, DC

JANUARY 20, 19451

11:55 A.M.

War is never far from the minds of Americans, even on a unique day in the nation’s history.

Hope that the Second World War would end by New Year’s Day has long been abandoned. Wounded soldiers, many on crutches, are among the seven thousand invited guests tromping through harsh weather to witness Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s swearing-in as president of the United States. This will be the first inaugural address during wartime since Abraham Lincoln spoke eighty years ago, in 1865. Also, this is the first inaugural to be held at the White House, in “the president’s backyard,” as the South Lawn is known. Finally, this is the first and only time an American president will be sworn in for a fourth term.

A light snow dusts the White House on this Saturday morning as spectators show their invitations to the security guards, then pass onto the wintry lawn. It stopped snowing three hours ago, but the skies are threatening yet another storm. No seats await, so the seven thousand guests remain standing—even those soldiers balancing on crutches. Thirteen of Roosevelt’s grandchildren pose for a newsreel cameraman atop the stairs of the South Portico, just a few steps from the podium. FDR’s chief of staff, Harry Hopkins, stands ground level at the bottom of the stairs, fastidiously overseeing the proceedings.

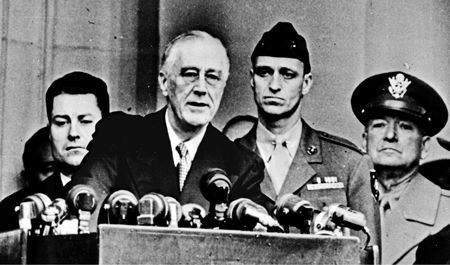

President Roosevelt speaking at his fourth inauguration ceremony

In addition to the veterans and dignitaries,2 a smattering of black faces can be seen in the crowd, reflecting Roosevelt’s hope for a more racially integrated nation. The diverse attendees stand side by side in the elements, awaiting the noon start. Wartime shortages of gasoline and lumber mean that the traditional post-inaugural parade will not happen, and the swearing-in ceremony promises to be brisk.

As the seconds tick down, the crowd presses closer and closer to the White House walls. Only a thin barrier of Secret Service agents and Washington, DC, police protect the curved outcropping known as the South Portico.

At the stroke of twelve, Rev. Angus Dun steps to the lectern to begin the proceedings. The Right Reverend is bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Diocese of Washington. Dun is a pacifist, which makes him an odd selection to deliver the invocation in a time of all-out war. Even more intriguing, Dun is visibly handicapped. He balances on crutches, having lost one leg to polio. His hands and remaining foot are deformed. Perhaps it can be said that the clergy is the only profession that would embrace a handicapped individual in this day and age, yet the fact remains that Dun has prospered. And unlike President Roosevelt, who would never dare reveal his handicap, Angus Dun3 does not hide who he is. Thus it is fitting that just eighty-three days hence, at a time when such fears will be completely meaningless to FDR, Angus Dun will also lead prayers at the president’s funeral service.

* * *

Harry S. Truman, the sixty-year-old senator from Missouri, steps to the lectern to be sworn in as vice president. This is a time of austerity in America and around the world, so Truman and Roosevelt have chosen to forgo formal dress, preferring instead to wear dark business suits.

The new vice president places his left hand on a family Bible and raises his right to take the oath of office. He is a small, wiry man with an infectious grin, a man unafraid to cry in public but able to conceal his emotions when a situation turns competitive. Those unlucky enough to sit across the poker table from Harry S. Truman know this all too well. The S does not stand for anything; that single letter is his actual middle name. It was once Truman’s dream to attend West Point, but poor eyesight ended that ambition, making necessary the glasses he now wears. Truman, however, fought as an officer in the First World War. He aced the vision exam before his induction into the military by memorizing the eye chart.

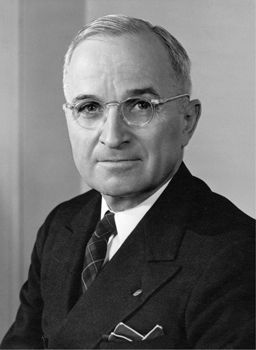

President Harry S. Truman in 1945

Truman made the leap from a small-time county commissioner to Missouri senator just ten years ago. And at times the power in Washington still overwhelms him. Now is such a moment. He and FDR barely know each other, and the president clearly has no interest in asking Truman’s advice about how to run the country. It is also widely known that Truman did not campaign for this new job. In fact, he was initially reluctant to accept the vice president’s spot on the ticket when it was offered at the Democratic Convention last July. Foreseeing his own death, FDR had sought to replace his current vice president, Iowa native Henry Wallace, with someone less liberal and less inclined to align himself too closely with the labor movement. Roosevelt studied the dossiers of several candidates before settling on the pragmatic Truman.

But it was left to a friend and longtime political aide to convince Harry Truman to take the job. “I think, Senator, that you’re going to do it,” Edward D. McKim told him one night during the Chicago convention.

Truman got angry. “What makes you think I’m going to do it?”

McKim knows Truman well, and has a deep knowledge of how to push his good friend’s emotional buttons. “Because there’s a little ninety-year-old mother down in Grandview, Missouri, that would like to see her son become president of the United States.”

Truman teared up at the image of his mother. He stormed out of the room and refused to speak with McKim.

McKim was unfazed. He was well aware that fear played a part in Truman’s reluctance, for there was enormous pressure in accepting the Chicago nomination. “The consensus of opinion at the whole convention was that whoever was nominated for the vice presidency would eventually be president of the United States.”

And this does not mean waiting four more years until Roosevelt finishes his term. The president’s ill health is now a very poorly kept secret. Even as he swears the oath of office, Truman is quite certain that FDR will soon die—and that he will become the thirty-third president.

That is a notion, in the words of another Truman confidant, “that scares the very devil out of him.”

When the ballots were finally cast at the 1944 Democratic Convention, 1,176 delegates were asked to select the party’s new vice presidential candidate. Senator Harry Truman garnered 90 percent of the vote. Incumbent vice president Henry Wallace received just 9 percent.

Now, eleven weeks after the Roosevelt-Truman ticket’s landslide victory over Thomas Dewey’s Republican ticket, the crowd in Washington bears witness as Truman recites the oath. It is an awkward moment, for the man swearing him in is none other than Henry Wallace, the ultraliberal vice president he is now replacing.

Soon it is done. Harry Truman is the vice president of the United States.

Now Franklin Delano Roosevelt is helped to his feet and begins the shuffle of hips and swinging of leg braces that approximates his version of a walk. Supported by the steel bands around his legs and hips that are concealed beneath his dark blue business suit, Roosevelt stands before the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Harlan Stone. His left hand rests on the same Dutch-language Bible as was used in his first three inaugurals. Per FDR’s tradition, the Bible is open to 1 Corinthians 13, which teaches that of the three virtues, faith, hope, and love, the greatest trait mankind can display is love.

FDR has six children and is devoted to his thirteen grandchildren, who now watch him from just a few feet away. He also has a wife to whom he has remained married for forty years. In his own way, FDR loves them all.