So even though the date was fast approaching, Stalin decreed that January 1 would mark a new annual celebration throughout the Soviet empire. The people would not honor the birth of the baby Jesus. The only religion in the Soviet Union was communism, and Stalin himself had demonstrated this, in 1931, by ordering that the Christ the Savior Cathedral, a towering monument to Christianity right in the heart of Moscow, be blown to bits.

No, the Russians would not celebrate the birth of Christ. Never. Instead they would celebrate the great moments of Soviet Russia’s twenty-seven-year-old history.

Stalin arranged to have one of his top henchmen, Pavel Postyshev, publish a letter in the state newspaper, Pravda. Such a letter changing Soviet state policy would never have been printed without Stalin’s direct approval. To do so would have been a crime punishable by death. So Postyshev, who just two years earlier had engineered a man-made famine to ensure the death of hundreds of thousands in Ukraine, clearly spoke for the Soviet dictator. In his letter, Postyshev spoke of a new Soviet holiday. Instead of Santa Claus, a white-bearded figure named Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) would travel across the Soviet Union in a sleigh pulled by three horses, delivering presents on New Year’s Day. Instead of the Christ child, a youngster named New Year’s Boy would be pivotal to the celebration.

And of course there was the tree. No longer would the holiday tree be seen as “religious dope” and a “savage custom,” as it had been known throughout the Soviet Union. “It is time to put an end to this wrongful condemnation of the tree,” Stalin ordered by proxy, thanks to Postyshev’s letter to Pravda. “Children’s New Year trees should be everywhere—in schools, orphanages, young pioneer clubs, cinemas, and theaters!”

Thus a holiday was born.6

Soviet toy factories began producing red stars to serve as tree toppers, along with New Year’s garlands and figurines of Grandfather Frost and New Year’s Boy. The Kremlin even opened its doors to Soviet children so that they might celebrate the Yolka, “fir tree.”

* * *

The elaborate staging of a contrived holiday had little effect on Svetlana. Soon, she was completely alienated from her father. The rupture came after she fell in love for the first time in her life, with Alexei Kapler, a Jewish writer and filmmaker twenty-two years her senior—almost exactly the same age gap as that between Joseph Stalin and the suicidal Natasha.

But there will be no marriage between Svetlana and Alexei. Joseph Stalin is determined to be the one and only man in Svetlana’s life. On this snowy Christmas Day in 1944, Alexei Kapler now resides five thousand miles away, in the harsh subzero temperatures and round-the-clock darkness of a snow-covered labor camp in Siberia, sent there for “anti-Soviet agitation.”

Alexei Kapler would spend ten years in a gulag for the crime of loving Joseph Stalin’s daughter.

Merry Christmas, Svetlana.

* * *

Christmas Day is coming to a close. Stalin finishes his thank-you notes and then turns his attention to reading dispatches from the Battle of the Bulge. He suspects that Adolf Hitler is preoccupied with the Western Front, and perhaps thinks that the Soviet army is using the winter weather to regroup and refortify.

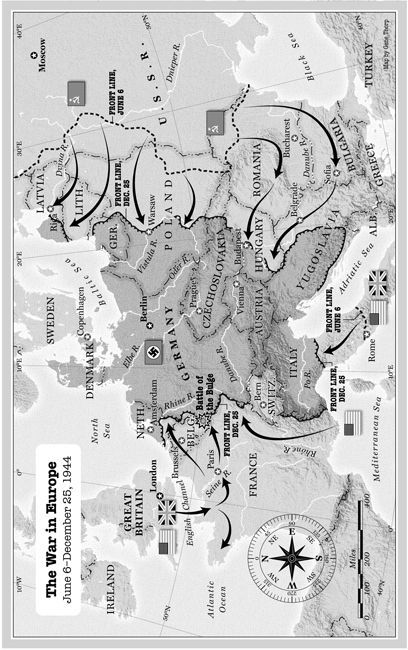

If that is the case, Hitler is wrong. Even at this very minute, the Soviets are hitting the Germans hard in Czechoslovakia and Hungary. And once these nations are wrested from Hitler’s grasp, Stalin has every intention of pushing north into the heart of Berlin—planning to get there before the American and British dash, so that he can have all the glory.

If all goes according to Stalin’s plan, Eastern Europe will soon be under the control of the Soviet Union. Stalin’s troops are not liberating people from the Nazis, they are enslaving them.

With the Americans and British bogged down in eastern France, Joseph Stalin orders his armies to step up their attacks in order to expand his global empire.

The race is on.

12

THIRD ARMY HEADQUARTERS

LUXEMBOURG CITY, LUXEMBOURG

DECEMBER 26, 1944

2:00 P.M.

George S. Patton is tired of breaking his promises. The air in his palatial headquarters, which serves as an old-folks’ home in peacetime, is thick with the smell of cigarette smoke and the clack of typewriters. Junior officers and enlisted subordinates make sure to keep their distance from the volatile general as they range in and out of the command post, not wanting to incur the wrath of a clearly exhausted Patton. When a message arrives from Dwight Eisenhower, stating that he “is very anxious that I put every effort on securing Bastogne,” Patton nearly explodes.

“What the hell does he think I’ve been doing for the last week?” Patton will write in his diary, careful, after all his trouble, not to criticize his boss in front of the headquarters staff.

But privately Patton seethes at Eisenhower’s poor tactical choices. The Seventeenth Airborne, Eleventh Armored, and Eighty-Seventh Infantry divisions have all been moved one hundred miles back to the French city of Reims as reserves, just in case the German breakthrough goes even deeper into the American lines. “We should attack,” he complains to his staff. Patton could sorely use the additional firepower those units would bring to the relief of Bastogne. Instead, they sit in the patient defensive mode that Patton deplores.

“We should attack.”

The general broods and studies maps of the front lines. Patton’s tank crews are spread out over a thirty-mile-wide front, locked in a stalemate with their German opposites. They are gaining little ground and losing too many men and tanks as they battle for each and every inch of Belgian soil. A German ambush in the hamlet of Chaumont cost Patton eleven Shermans and almost a hundred men. The Fourth Armored also lost scores of tanks in a night attack that advanced their position just a quarter mile.

Even worse is that as soon as the Third Army passes through a town and reclaims it for the Allies, German paratroopers follow right behind. Thanks to intercepted radio messages, they know that the Americans plan to remain constantly on the attack. Thus they move in and take back the towns as soon as the Americans leave.

Dead Americans now lie frozen in the fields outside Bastogne, their faces turned the color of “claret,” in Patton’s own description, from the blood pooling after death. In his journal, Patton keeps a detailed tally of Allied and German casualties, and knows that Germans are dying in far greater numbers.

But casualties tell only part of the story. The German lines are holding fast. Patton and the Third Army are stuck, and Tony McAuliffe and the 101st Airborne are now enduring yet another day in the violent hellhole of Bastogne. The dirty streets are choked with rubble, and small fires caused by artillery shells are left to burn. The only place a man can feel safe from the constant shelling is hunkered underground in a cellar, where he is at least partially protected from falling debris—thus Tony McAuliffe’s decision to relocate his command post to the Belgian barracks. But while there is temporary safety in these bunkers, the tradeoff is the thick, asphyxiating smell of unwashed bodies and clouds of cigarette smoke. And because the soldiers and three thousand civilians that now share Bastogne are reluctant to leave their cellars for any reason, there is also the scent of an aromatic compound known as phenol, or carbolic acid, which is sprinkled on the floors to cover the scent of human excrement and urine.

Elsewhere in Bastogne, American wounded lie atop squalid litters inside an old garage turned into a make-shift field hospital. They cannot help but hear the rasp of the bone saw as army surgeons cut away the destroyed arms and legs of their fellow paratroopers.