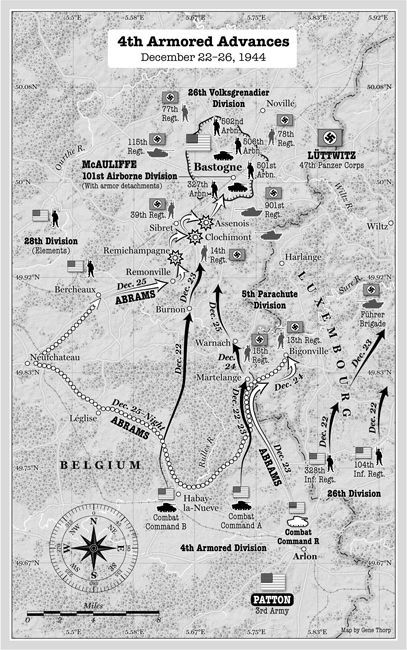

The request goes to Major General Gaffey, who passes it along to George Patton.

Patton orders the attack.

* * *

Abrams soon orders all available American artillery in the area to launch an immediate barrage to soften the German defenses. The thunder of 155 mm guns soon booms across the Belgian countryside, as shell after shell is lobbed on the German positions hidden within Assenois and its forests. In all, more than two thousand rounds will fall on the Wehrmacht fighters today.

“Get those men in Bastogne,” Abrams commands his tankers. He waves his arms high in the air, and his tanks churn forward.

There is nothing quick about their movement. The Sherman’s top speed is just thirty miles per hour. Nor is there any way to conceal their advance. Thanks to the artillery barrage, the Germans know the Americans are coming. They can now clearly see Abrams and his line of Shermans and halftrack armor steering down the hill into Clochimont.

Abrams closes the hatch and conceals himself inside the three-inch-thick steel of the turret as his and the other Shermans burst through Assenois’s ancient town square. German artillery explodes all around. One shell knocks down a telephone pole, blocking the road and bringing the column of five Shermans and a halftrack to a lurching halt.

The pole has to be moved.

Abrams and several other men immediately climb out of their tanks. With sniper fire pinging off steel and glancing off the rutted road, they work as a team to swing the heavy pole out of the way.

Then it’s back into their Shermans. Behind them, a column of infantry secures Assenois, and will stay there until the mopping-up action is complete. A second column of foot soldiers travels with Abrams’s tanks as they move toward the concealed German positions in the forest alongside the road through Assenois.

American tank destroyers prepare to advance on Bastogne in January 1945

Rather than simply race through the town, Abrams chooses to level it. Every building that might conceal a German becomes a target. The Shermans load and shoot their big 76 mm guns as many as seven times per minute. Meanwhile, the infantry ruthlessly hunts down Germans, screaming, “Come out,” to induce them to surrender.

“But they wouldn’t,” one American soldier later remembers. “One poked his head out of a foxhole and I shot him in the neck.”

Trouble soon strikes. The jeep carrying the artillery observer is hit before he can give the signal to halt the barrage. The American artillery continues to rain down shells on Assenois, unaware that Abrams and his men are now inside the town. Three hundred and sixty rounds of artillery shells are fired by the American big guns. Geysers of earth erupt throughout the town as each shell forms its own deep crater. Frantic radio calls from Lt. Charles Boggess, who now leads Abrams’s spearhead in his tank, Cobra King, go unheard. Americans and Germans both are killed. The American shelling and the nonstop tank barrage are completely decimating Assenois, wiping it off the map as if it never existed. Plumes of fiery smoke and dust turn the daytime sky black. Finally, a spotter plane pilot sees the trouble and orders the artillery to stop.

The Germans lay Teller antitank mines on the road in a last-ditch effort to stop the American breakthrough. None of the Shermans is hit, but an American halftrack explodes when it hits a mine, killing the driver and again bringing the American column to a complete halt. Thinking quickly, Capt. William Dwight, Abrams’s operations officer, risks his life by climbing out of his tank and exposing himself to fire as he clears the mines out of the road by hand.

Through the dust and smoke, Pvt. James R. Hendrix, the son of an Arkansas sharecropper, spots two concealed German 88 mm guns. Next to them, hiding in a foxhole, are two Wehrmacht soldiers. Hendrix crouches low and moves toward them through a hedgerow, then presses his body flat in a shell crater as he creeps up on the enemy. Hendrix is just five foot six, and weighs only 125 pounds, but he shows no fear as he prepares to attack the German foxhole alone.

“A feller just figures if it’s his time, it’s his time, and that’s all there is to it,” is how he later explains his courage.

Screaming, “Kommen heraus!”—“Come out!” in German—Hendrix runs up to the foxhole with his M-1 aimed squarely at the enemy soldiers.

They don’t surrender. Hendrix is forced to shoot one soldier in the head and then smash in the skull of the other with his rifle butt.

“I got their guns and got back in my shell hole and started hollering, ‘Kommen heraus,’ again, and sure enough, them Germans began coming out from around the different foxholes, and 13 gave up,” he will later recall, describing the action that will earn him the Congressional Medal of Honor.

Later that night, in fierce, pitch-black fighting that will see few prisoners taken on either side, Hendrix will add to his legacy by personally knocking out two German machine-gun nests and also braving sniper fire to pull a wounded American from a burning halftrack.2

The battle in the forests surrounding Assenois will continue long into the night, but by afternoon the Americans have carved a small channel through the German lines. The path is less than four hundred yards wide, and Germans are poised on both sides, prepared to counterattack and once again close the road. But for now, American tanks are advancing toward Bastogne.

Boggess fires on a German pillbox on the outskirts of Bastogne. The smoke clears. First Lieutenant Charles Boggess opens the turret of Cobra King and lifts his torso up through the opening. Soldiers in uniform crouch in foxholes across the road to his right, their guns aimed his way. “Come here! Come on out! This is the Fourth Armored,” he shouts. He does not yell in German, hoping to find an American reply.

There is no answer. A tense moment passes. With his head and chest completely exposed to rifle fire, Lieutenant Boggess considers his options.

The Sherman 76 mm barrel pivots until it is aimed directly at the foxholes. Pvt. James G. Murphy has already loaded a round, and the gunner, Cpl. Milton Dickerman, awaits the order to fire.

“Come on out!” Boggess nervously shouts again.

A lone soldier walks forward.

“I’m Lieutenant Webster, of the 326th Engineers, 101st Airborne Division,” he said. “Glad to see you.”

Bastogne has officially been relieved.

Cobra King rolls into the heart of the town, followed by a convoy of Sherman tanks.

Soon, “Abe” Abrams appears.

“Gee, am I mighty glad to see you,” says Tony McAuliffe.

Patton’s audacious gamble has succeeded. He awards Abrams with the equivalent of a second Distinguished Service Cross and praises him as America’s top tank commander—even saying that Abrams is a better tank commander than he.

* * *

The next morning, December 27, 1944, George Patton once again walks to the front of a small Catholic chapel and drops to his knees in prayer.

“Sir, this is Patton again,” he begins with an air of contrition. “And I beg to report complete progress. Sir, it seems to me that You have been much better informed about the situation than I was, because it was that awful weather which I cursed You so much which made it possible for the German army to commit suicide. That, Sir, was a brilliant military move,3 and I bow humbly to Your supreme genius.”4

* * *

The German advance stalled on Christmas Eve 1944. Basically, the Germans overran their supply lines. And without ammunition and gasoline, they were unable to wage an offensive campaign. The continued progress of Patton and his Third Army eventually spelled doom for Operation Watch on the Rhine. By January 25, 1945, the Germans had retreated back to the same positions they had held at the start of the offensive six weeks earlier. Thus ended the last great German attack on the Western Front. “The relief of Bastogne is the most brilliant operation we have thus far performed, and is in my opinion the outstanding achievement of this war,” Patton writes home to his wife, Beatrice.