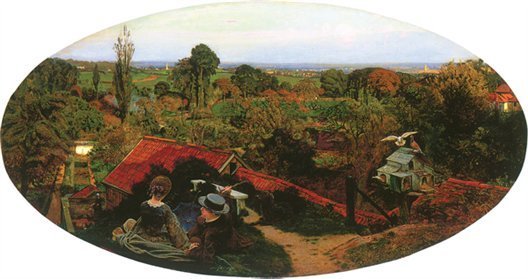

Ford Madox Brown,

An English Autumn Afternoon,

Hampstead: Landscape, 1852-1855.

Oil on canvas, 72 x 135 cm.

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

Moreover, instead of painting over robust grounds, he used very light ones, and waited for them to dry completely so that they would behave like canvas or wood. He assumed that if these light colours re-emerged with time, they would lighten his painting instead of darkening it, which is indeed what happened. Today, none of this is a secret, but at the time when Watts, Hunt, and Millais were starting out, it took rare insight to understand it and great energy to act.[28] Finally, worried about mixing colours with different bases and producing disastrous chemical combinations, Watts had the idea of placing colours next to each other instead of layering them. For example, if he wanted to create a reddish-yellow hue, instead of mixing red and yellow paint together he would add a touch of red next to a touch of yellow. As much as possible, he substituted juxtaposition for mixture, since beyond a certain distance they produce approximately the same effect on the eye. These processes, which the pointillists of today celebrate as new discoveries, connect Watts to the great Pre-Raphaelite school. He sought the same things as they did, original poses and strong colours, at the same time that they did, and though he was not a member of their group, its spirit was a continuous inspiration to him.

Thus, taken as a whole, from Madox Brown to Millais and from Watts to Rossetti, from the Westminster cartoons to The Last of England, from Isabella and Lorenzo to the Huguenot, and from The Annunciation to Dante’s Dream, the 1850 movement was the following: new men, seeking a new art, substituting curious, individual, novel poses for banal and generalising ones, and strong colour applied without underpainting, glittering with juxtapositions, for fluid colour reinforced by superpositions. In short, expressive lines instead of decorative ones and bright colours instead of warm ones. This, put simply, is what Pre-Raphaelitism was. And the rest is only mincing words.[29]

But there is a residue of truth that to be found in the depths of the Pre-Raphaelite theories, and this “precipitate” that remains in the still used for the analysis, after the concepts of high aesthetics have disappeared in smoke, should not be disregarded. To seek, as in the details of a Meissonier, precise movements instead of vague movements, and achieve, as through the extravagant imagination of Gustave Doré, expressive forms instead of purely decorative ones, is a great step, and this is exactly the step that needed to be taken in 1850. When generalisation reigns supreme in academic art, in a school, this school is lost; it becomes necessary, through some process, to undo the bundle of rules, throw away the stereotypes, break the moulds, chase away the models who strike poses like Jupiter thundering or Venus emerging from the sea of their own accord, and mix up all of the pompous lines that express no particular attitude, but only a state of the body and the spirit applied to an entire set of ideas and feelings, because in this case mere skilfulness is taught instead of careful study, and the student is led to the result without understanding the means.

William Holman Hunt,

Our English Coasts, 1852

(“Strayed Sheep”), 1852.

Oil on canvas, 43.2 x 58.4 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

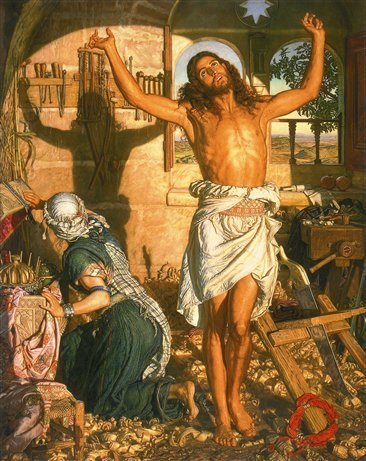

William Holman Hunt,

The Shadow of Death, 1870-1873.

Oil on canvas, 281 x 248 cm.

Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester.

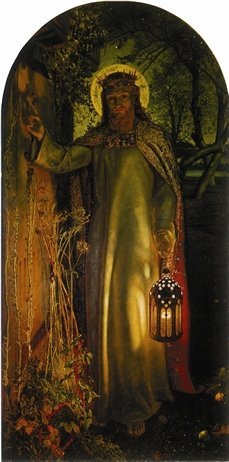

William Holman Hunt,

The Light of the World, 1851-1853.

Oil on canvas, 125.5 x 59.8 cm.

Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester.

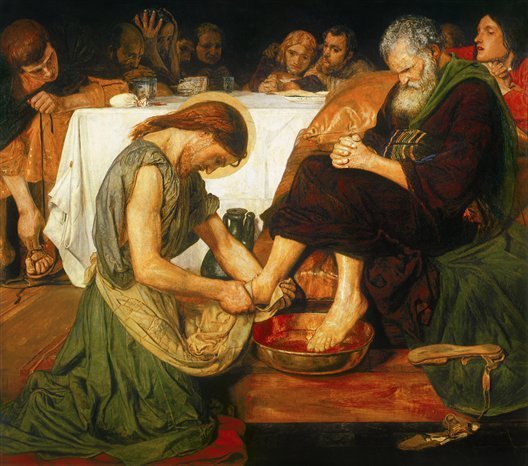

Ford Madox Brown,

Jesus Washing Peter’s Feet, 1852-1856.

Oil on canvas, 116.8 x 133.3 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

When one wishes to outline from memory Tatius’ arm throwing the javelin (from the painting of The Sabines), one must stop and ask if this is the most personal pose that he can be given. This is not because generalisation in art should be forbidden (whenever art is elevated, it generalises), but because in order to attempt the expression of a general idea, one must know the specific ideas that gave rise to it. Before permitting oneself to make an image that summarises, one must know what is being summarised. Before making an image that ennobles, one must understand that which ennobles. In a word, in order to speak in literary language, one must be able to speak in common language. The Academy in 1850 could no longer do this. For them, the generalisation of forms was no longer the highest challenge to be tackled when one had overcome all others, but a collection of inherited recipes, magic formulae that are passed on without analysis, which are to be used without understanding what is behind them.[30]

The step taken with colour was no smaller. No one would think to reprimand Titian, Rembrandt, or van Dyck for their warm tones, nor be scandalised if they obtained them through painting over layers of robust colour. But the formulae which tried to codify their processes without truly understanding them are deplorable, and because they facilitate that which should be done with difficulty, because they spare a necessary effort and make it possible for the student to easily attain passable results, they are unable to give him the means to achieve better. From the day when a school begins producing excellent copyists of old paintings instead of training its students to create, it is in the wrong. When it teaches the avoidance of difficulty instead of the skills to fight against it, it loses its reason for being. Achieving transparency by painting over bitumen is easier than doing so through laying down solid colours individually. Achieving contrast through the false opposition of blackish and luminous regions is easier than obtaining it from a correct relationship between colours. But this easy contrast is of lesser quality and this easy transparency is a peril for the future. The bitumen with which Haydon conscientiously coated his canvases before painting, probably to obtain the subdued colour that the English had held in such high esteem since Reynolds, the large areas of black that the members of the Academy included in their compositions to restrict the light to the chosen places, these are the traditions that needed to be broken at any price.

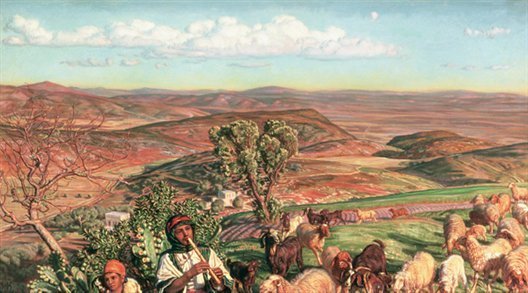

William Holman Hunt, Plain of Esdraelon

from the Heights above Nazareth, 1877.

Oil on canvas, 41 x 75 cm.

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology,

University of Oxford, Oxford.

The Pre-Raphaelites, by always painting on a white canvas and always using “the solar system”, as Ruskin said, for their lighting[31] – that is to say plein air with no preconceived ideas about light – went perhaps too far, but in doing so they saved English painting. When one examines the early Pre-Raphaelite paintings, Millais’ Lorenzo and Isabella, for example, one is astonished by the naturalist and even impressionist discoveries that this twenty-year-old painter made thanks to the subtlety of his eye. There is no diffuse shadow without bright points, without reflections of the surrounding luminous objects. There are imperceptible gleams even in cast shadows, shadows of the nostrils in the figure of Lorenzo, and of the hair ribbons in that of Isabella, and this continuous dispersion of the effect brings fluttering light and lively animation to even the driest painting. It is bright and joyous compared with the best academic paintings of 1849. This same quality, though to a lesser degree, can be seen in Hunt’s paintings; there is no region completely enveloped in shadow. Everywhere that the painter saw light, he painted it, down to the tiny hand of the kneeling child who is holding a fly-swatter, in the painting Finding Jesus in the Temple. This laborious, tireless, exasperating search for the varied effects of the sun, for its blows and counterblows, its upstrokes and downstrokes, its arpeggios and trills, its floods and trickles, its thousands of reflections and counter-reflections, selecting nothing, is upon first glance disconcerting and irritating, like the story of a nasty fairy that forces a poor girl to find a pearl necklace scattered in the forest. But bit by bit, the skein unwinds, the threads untangle, and the whole that nature desired appears, and though the colours remain quite unpleasant, the bright spots are seen to correspond and harmonise, and the pearls are strung together one by one to form the necklace. Upon first looking at Holman Hunt’s Unwatched Flock, this painting resembles a wound.[32] These blood-red sheep in indigo bushes, on rocks like nougat under an uncompromising sky, lead us to think of the worst excesses of our luminists, and one wonders if this may be one of the first manifestations of the plein air school – if the purple hair of Mr Besnard did not somehow descend from the red sheep of Holman Hunt by some bizarre filiation. But though these works are imperfect, they are valuable as attempts. These tones placed boldly next to one another are often garish, but sometimes yield a strong vibration. With all his extravagance, Hunt made colour sing, and it had been in a deep sleep before he came along. Sometimes this is but a brief flash, but in its light we see how right the P.R.B. were to leave the studio for the fields and leave misunderstood tradition for nature, even if they revealed it imperfectly. All this is but a single word, but those who pronounced it had a vague premonition of the fertility of countering the “Renaissance system” with the “solar system”. Indeed, the P.R.B. often passed quite close to modern discoveries, and several times they stammered out the first words of an aesthetic revolution. We have the same impression when looking at them as when reading Vauban’s Dixme Royale; this is a new world, not yet clearly visible, but half-revealed through prophecy and premonition. Thus, it is incorrect to say that by reducing Pre-Raphaelitism to original lines and bold colours, we lessen its role; on the contrary, we enlarge it. The name of the Pre-Raphaelite magazine was well chosen, for their work contained the Germ of all contemporary painting.[33]