Ford Madox Brown,

The Last of England, 1855.

Oil on panel, 82.5 x 75 cm.

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

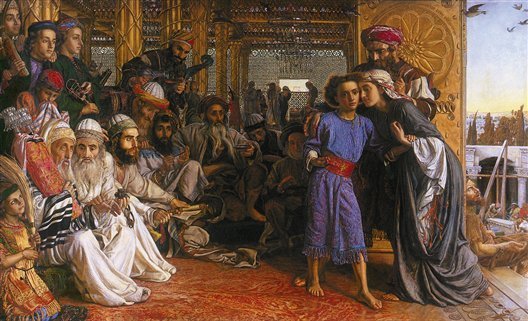

William Holman Hunt,

The Finding of the Savior in the Temple, 1854-1860.

Oil on canvas, 85.7 x 141 cm.

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

William Holman Hunt,

The Triumph of the Innocents, c. 1883-1884.

Oil on canvas, 156.2 x 254 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

Edward Burne-Jones,

The Merciful Knight, 1863.

Watercolour, 101.4 x 58.6 cm.

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

Whatever their theories or those of their friends were, whatever goals they established or were identified with, the Pre-Raphaelites profoundly changed the idea of line and colour for their compatriots. Perhaps without knowing it, and certainly without understanding very clearly, they introduced in England the habit of clearly expressing a subject through meaningful poses and pursuing vivid colour with simple, direct means. Could this give England new masterpieces? We can respond only by looking at the principal manifestations of contemporary English painting, but it surely must have given England new works and a national art. Perhaps the Pre-Raphaelites did not win the war that they were waging, but they won another. Perhaps they could not prove that nature is the last word in art, but they proved that it is the first, and that the efforts of a host of talented and strong-willed men, whatever the goal that they choose may be, are never wasted.

When we look today, in retrospect, at this band of Pre-Raphaelites riding off to conquer the Holy Land of art, we seem to see one of the last crusades. They all started off in 1848, wearing the same armour and fighting under the same flag. How many arrived home in 1895? Some, like Deverell, died along the way, before they could see the shining roofs and towers of the Holy City. Others, like Millais, became kings of some island and forgot, among the honours showered upon them by the infidels, the purpose of their expedition. Still others, passing by some monastery on a hillside, told themselves that the road was quite long and their return quite uncertain. They stepped inside, drawn in by the bells, those sirens of the heavens, and no-one knows what became of them... Some made their way all the way to the Jerusalem of art and planted their flag in its soil. But which flag? It had certainly changed, the Pre-Raphaelite standard of the early days! The wind of battles and the patina of the years had cooled its uncompromising colours! Nevertheless, it flutters atop one of the high points of the century, as a testament to the noblest attempt, the most tremendous effort undertaken by modern artists. And we can say of Pre-Raphaelitism that it was not useless for the rejuvenation of an old world.[34]

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Horatio Discovering

the Madness of Ophelia, c. 1864.

Oldham Gallery, Oldham.

III. Intentions

What then does such a singular art aim at? Obviously something other than merely pleasing the eyes. “You will find that the art whose end is pleasure only,” says Ruskin, “is pre-eminently the gift of cruel and savage nations, cruel in temper, savage in habits and conception; but that the art which is especially dedicated to natural fact always indicates a peculiar gentleness and tenderness of mind.” “The greatest art creates beauty, but does not make beauty its purpose,” adds Collingwood. Thus English painting has a goal that can shed some light on its distinctive features, an idea behind the face or the painting that explains its flaws, a programme which is not that of depicting beautiful torsos and rich draperies. One is convinced, when looking at these masters’ works, as when reading those of their critics, that this extra-aesthetic goal has a high place, perhaps the highest, among their preoccupations.

This goal is first of all to address all the faculties of man: spirit, intelligence, memory, conscience, heart, and not only that part of us which sees, which is moved by seeing, and which imagines. “Art,” said Mrs Russell Barrington, “should elevate us through its imagery to a more complete view of the human condition than that provided by everyday life.” Ruskin adds that “perfect art reveals the entire man.” To do this, the artist himself must have a complete form of intelligence. Turner and Walker were of this sort, but all of the worthwhile painters resembled the artist-poets William Blake, Bell Scott and Rossetti, in the extent of their knowledge and interests. William Morris, who made tapestries and stained glass, was also a fine poet and the most appealing writer for the socialist party. Leighton spoke many languages. Burne-Jones, who went to Oxford, was an exquisite scholar of legendary literature, Watts was a philosopher, Hunt was an exegete, and Alma-Tadema was an archaeologist. Poynter gave lectures as Reynolds once did. Mr. Stephens and the late Hamerton had always written better than they painted, Hook was interested in sociology, and Birket Foster in ornithology. Millais and Herkomer both brilliantly expressed ingenious ideas on all the arts, and the latter lectured on them at Oxford. We are struck by the breadth of their culture. All of the questions pronounced in this world found an intelligent echo in their studios. All of the winds that passed over the masses incited a particular vibration in the souls of these artists. When painting was not being done in Mr. Cl...’s studio, there were lectures on theology, and when La Belle Dame Sans Merci had finished walking through the flower garden, among M. II. II...’s rhododendrons in Hampstead, Mr. Gladstone came there to prepare a speech on Home Rule. Such artists could act upon all of the spectator’s faculties because all of theirs were active, and they could teach a lot because they had themselves learned much.

What they taught us is above all their idea of work. The sort of improvisationist who makes a horse or a Harmony in two days, like Fromentin or Whistler, and who asks two hundred guineas for it under the pretext that he has been preparing it for thirty years, is extremely rare among the English. Most of their artists share a disdain for easy success, are persistent in their work, and are determined to never be satisfied so long as they still find something better in themselves than in their work. They have conscience, if this word, the most beautiful that can be said of a man, had not already lost its value by being abusively applied to artists in whom it is completely lacking. Madox Brown spent four years making his Last of England, which includes only two main figures, and fifteen years painting the frescoes in Manchester Town Hall. Mr Hodgson said of Walker that “no artist has ever struggled so much while working. It was painful to watch him.”[35] Hunt spent an entire life of continuous labour on a few small paintings, as many as some painters exhibit in a year on the Champs de Mars or in a club. Watts painted hundreds, but he kept all of them in his studio, considering that only two out of this number did not need any retouching. Burne-Jones spent seven years planning and executing his Briar Rose, which does however include four panels, each containing several figures. He sketched his Wheel of Fortune in 1871, but did not begin painting it until 1877, and finished it in 1883. One must read Mr Hamerton’s stories about camping in the moors of Lancashire to imagine the effort and time that a Pre-Raphaelite could devote to studying a tuft of ferns in the field, frond by frond. In his tar-sealed wood and tile hut, which predated Mr de Nittis’s famous roulotte by ten years, Mr Hamerton had to endure cold, humidity, gusty wind, the curiosity of peasants who came along, believing that they had seen him executing the turns and attacks of night hunters, and the inane questions of neighbouring country gentlemen, and all of this for months on end.[36] This same desire for accuracy inspired Mr. Boot to paint his ocean and river scenes from on board a studio-boat equipped to travel in both salt and fresh water, which he named the Thelis and whose voyages are well-known among English artists. Alma-Tadema was very productive, this is true, but he professed and proved through his own example that nothing is accomplished without difficulty. He showed no leniency toward his own work. If one bit, which had cost him a thousand efforts, seemed useless or dangerous to him: “Art lives on sacrifice!” he would say, and would scrape it off. If an entire work did not seem good to him, he destroyed it without hesitation, in a valiant caprice. In 1859, one of his paintings sent to the Brussels exhibition was refused by the jury. It depicted a fire. He asked his friends to come see this painting in his studio, to tear holes in it and pass through it like a door. He gave the example himself, by jumping headfirst into the flames of his painting. This joking about was not without courage. It demonstrated the necessity of effort, the price of steadfastness, and the strength of the will. This was the first lesson given by English painting.