Ford Madox Brown,

Walton-on-the-Naze, 1859-1860.

Oil on canvas, 84 x 174.2 cm.

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

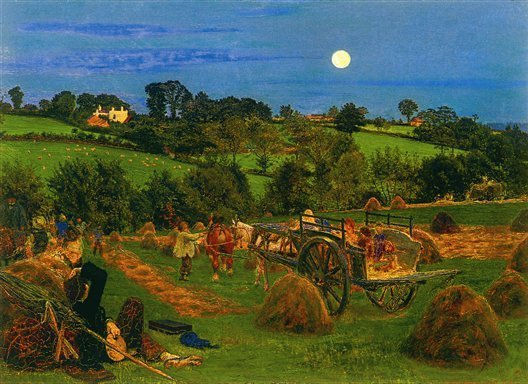

Ford Madox Brown,

The Hayfield, 1855-1856.

Oil on panel, 24.1 x 33.3 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

Thus, there was something more lasting than the Pre-Raphaelite theory. There was an idea that united these innovators more closely and guided them for longer. But in order to find it, one must leave theory behind and examine their practices, stop consulting the newspapers where the P.R.B. members wrote and go into the museums and the galleries where their paintings are – put simply, one must judge them not by their words, but by their deeds, by their works. Then one sees, in all of them, and to the same degree, a furious effort, a desperate attempt to escape the inexpressive gestures and lifeless colours of the Academy in 1850. Whatever work one stands before, whatever master one chooses, at whatever period one considers his work, excepting the second half of Millais’ life, one finds these two characteristics: original poses and brilliant colour. The heads are perhaps inclined too far in meditation, the arms are sometimes subtly more rounded than necessary to attain a novel pose and express something new with the human body, like the branches of fruit trees that are forced into certain strange poses along a trellis. This desire to delve into the meaning of the slightest gestures, to restore meaning to the most vulgar interplay of muscles, is often carried to the point of mania. But on the other hand, this insistence on original poses often simply means remaining true to nature and changing the false aspect of a classical pose. The colours sometimes shriek from being juxtaposed without transition, from being left raw and unconcealed, and the brushstrokes, clumsily applied while working towards a difficult shade, are upsetting to look at, as the painter’s prejudices kept him from covering up his laborious process of trial and error. But, beneficial or not, these same characteristics are seen everywhere. Whether or not these are faults, the expressive originality of poses and the raw brilliance of colour can be seen in any Pre-Raphaelite painting, while they are completely lacking in the works that preceded them. They can be seen in Madox Brown’s work Christ washing Saint Peter’s Feet in the Tate Gallery, in Saint Peter’s deeply bowed head, in his furrowed brow, in his knees bent up under his chin and his hands joined around his knee, in all these aspects of the human machine straining to express the state of difficult reflection that envelops the apostle. This is the same highly significant pose that Holman Hunt would later give to the Rabbi Johanan ben Zakkai, who is listening to the boy Jesus in the Temple. The desire for brilliant colour can be found in the virulence of the basin’s copper tones and in Saint Peter’s feet. These characteristics are again found in Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix, only a few steps away from Madox Brown’s Saint Peter. Her head tilts painfully back, her throat opens out like a fan, her eyelids are half lowered and her mouth is half open, her hands rest passively on her knees in an attitude of excessive languor and prostration. She is entirely coloured in green, red, orange, and violet tones, extremely bright, but strong, solid, and even light when compared with the browns of the academic school.[27] We find these characteristics in all of Hunt’s works, and also in those of Millais until well after he is supposed to have abandoned Pre-Raphaelitism.

Ford Madox Brown,

Pretty Baa-Lambs, 1851-1859.

Oil on panel, 60 x 75 cm.

Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery, Birmingham.

John Brett,

Glacier of Rosenlaui, 1856.

Oil on canvas, 44.5 x 41.9 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

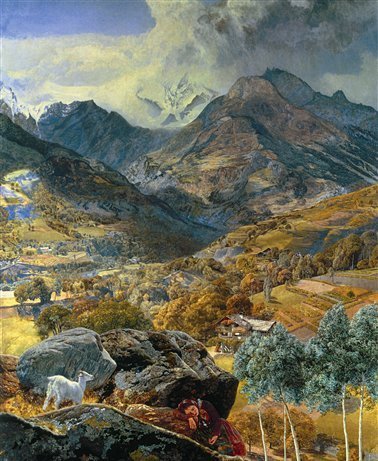

John Brett,

Vale of Aosta, 1858.

Oil on canvas, 88 x 68 cm.

Private Collection.

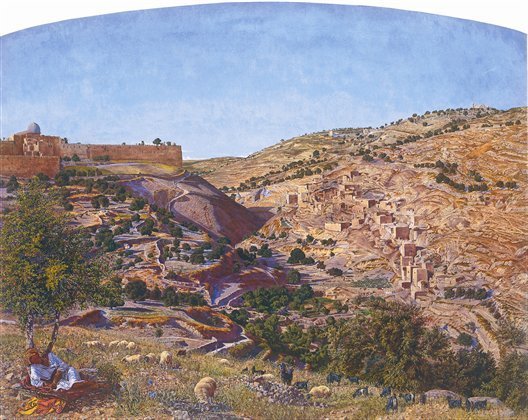

Thomas B. Seddon,

Jerusalem and the Valley of Jehoshaphat from

the Hill of Evil Counsel, 1854-1855.

Oil on canvas, 67.3 x 83.2 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

It is simply that they were achieved by a great variety of means. Some, such as Hunt and Millais early on, sought to attain original poses through the scrupulous observation of nature, which is an excellent place to learn originality because it offers an inexhaustible mine of new sights. While these painters devoted themselves to copying the distinctive characteristics of a particular model, Rossetti obtained the effect by reaching deep into his mind, straining his imagination, and forbidding his dream to speak until he had completely stripped it of all acquired forms, of all things drawn from the masters’ paintings. Thus he rarely painted his figures after nature, and many of them came directly from his imagination. Hunt and Millais sought new, varied, strong colours from the landscapes of Surrey, which they observed and copied in plein air, while Rossetti obtained them through audacious experiments in the studio, unexpected juxtapositions, and continuous changes in his palette, excursions whose futility often drove him to despair.

Finally, we find these characteristics in the work of one of their contemporaries, one of the winners of the Westminster competition 1844, who is never mentioned among the Pre-Raphaelites because he was neither a member of the Brotherhood nor one of its close friends. Working alone, he simultaneously accomplished the same reform as the Pre-Raphaelites through the same methods. I am speaking here of George Frederick Watts. He was older than most of the P.R.B., and had deplored the colourist practices of the Academy for even longer than they had. These practices are well known, and were similar in both France and England around 1850. One began by covering the canvas with bitumen and warm tones, with reddish brown, for example. Then, over this base which never truly dried since it contained bitumen, one added touches of cool tones, thereby immediately obtaining transparency and enchanting transitions. This method delighted beginners and more skilful painters alike with its ease. This devilish beauty later faded: the colours obtained from these highly thinned mixtures became muddy and dark. The reliefs, which were not supported by a sufficient thickness of colour, flattened out and receded into the canvas. The bitumen, which never hardened, lay trapped under the dried colours like water under ice and pushed its way out when subjected to changes in temperature, cracking the surface of the masterpiece. While Hunt and Millais were experimenting with painting on a plain white canvas, Watts also dared to take a course opposed to that of the misguided Academy. He decided to use only solid colours, resigning himself to the fact that he would not be able to obtain transparency rapidly and easily.