Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

Proserpine, 1874.

Oil on canvas, 125.1 x 61 cm.

Tate Gallery, London.

Thus began a period which, though not yet one of triumph, was at least no longer one of persecution. Each year, the Liverpool Academy awarded its prize to one of the P.R.B. brethren. Ruskin generously bought watercolours from Rossetti, and art dealers and rich collectors furnished them with grants. The Pre-Raphaelites redoubled their efforts. Millais, Hunt and Collins, the brother of Wilkie Collins, spent a summer in Surrey to study nature for the backgrounds of their next paintings. There, in the silence and calm of the countryside, they prepared works that will be forever celebrated. These were Millais’s Ophelia and A Huguenot and Hunt’s Hireling Shepherd and Light of the World. The world has perhaps never seen such single-minded devotion in observing details for a background. Millais wanted to paint his Ophelia floating in the river, her face turned toward the sky, her hands half-extended at the surface of the water, opened as if giving a blessing, her body half-stuck in grasses, dead willow leaves, nettles, daisies, and buttercups, her dress and draperies ballooning, slowly losing the lightness that had suspended them at the surface, everything that had been the young woman disappearing beneath the low foliage and the straight reeds, slowly flowing away with the water towards some great river and towards death. Each leaf of the tree that he copied, each verse of the poet whose words inspired him, caused Millais an infinite number of difficulties, for he wanted to remain faithful to both nature and Shakespeare.[16] Beside him, Hunt completed the background of his Hireling Shepherd and began that of his Light of the World, which depicts Christ crowned with gold and thorns, covered with a long tunic and the cape worn by priests when singing vespers. He carries a lantern and advances through the night in a countryside planted with trees. He stops before a door half hidden by weeds and parasitic plants, and he knocks. It is an expression of these words from the scriptures: “Here I am! I stand at the door and knock. If anyone hears my voice and opens the door, I will come in and eat with him, and he with me.” In order to perfectly reproduce the trees in the background and the ivy in the foreground, without inventing or generalising anything, truthfully and consciously and in the light that the subject demanded, Hunt compelled himself to work outdoors in an orchard for three months at night, from nine in the evening to five in the morning during every full moon.

When the two friends returned to London, they found benevolent, smiling faces and open arms. The hour of their success was approaching, and it came first to Millais at the 1852 Exhibition. His Ophelia and A Huguenot, though they were still attacked by a few critics, won over the rest of the crowd. Reproductions spread throughout England. One year later, he was elected an Associate Member of the Royal Academy and exchanged the letters P.R.B. for A.R.A. Next, Holman Hunt also triumphed with his Light of the World. The most elegant ladies came to visit his studio and admire the painting when it was still on the easel. Later, in 1855, their master and counsellor Madox Brown touched the hearts of the crowd with his Last of England, inspired by the departure of several unfortunate friends for Australia, where they had gone to try their luck. He depicted a young couple on a sailing ship, leaving their home country with an expression of deep despair on their faces.[17]

Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

Beata Beatrix, c. 1864-1870.

Oil on canvas, 86.4 x 66 cm.

Tate Britain, London.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti,

The First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrix

(Dante Drawing an Angel), 1853.

Watercolour on paper, 42 x 61 cm.

The Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology,

University of Oxford, Oxford.

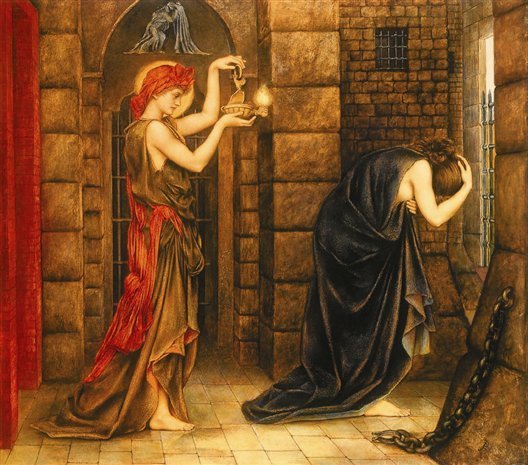

Evelyn de Morgan,

Hope in the Prison of Despair, undated.

Oil on panel, 58 x 65 cm.

Private Collection.

As for Rossetti, he had not exhibited anything since 1850, but at the end of 1856, feeling that success was certain, he reappeared in public and was greeted with enthusiastic applause. This was not at the Academy, but at an exclusive Pre-Raphaelite exhibition that brought together the principal works of the Brotherhood. On that day he presented the first watercolour of Dante’s Dream, which remains one of Rossetti’s most significant works. Hughes had just come on the scene with his triptych Eve of Saint Agnes, inspired by a poem by Keats. In the meantime, Stephens, one of the first P.R.B., had reached the post of critic of The Times, the newspaper in which his friends had previously met with so much hostility. Numerous artists hurried to line up under the revolutionary flag. Philosophers and poets, Carlyle, Tennyson, Coventry Patmore, and Dickens himself, the old adversary from the early days, escorted the triumphant victors. Finally, three young men, whose future roles were as yet unknown, arrived from Oxford and asked Rossetti to lead them toward the ideal: they were called Swinburne, William Morris and Burne-Jones.[18]

The Pre-Raphaelites amused themselves making portraits of one another, as soldiers might admire one another and celebrate victory once the battle has ended. And this was certainly a victory. It has been calculated that Millais, Hunt, and Rossetti earned no less than twelve million pounds between the three of them. But this was also the end of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. For a long time, their paintings had no longer been signed with the letters P.R.B. Several of the Brothers had left London: Woolner to go to Australia, Hunt for Palestine, and Collinson to take refuge in a monastery. Deverell died and, at that moment, the group split apart. In 1857, two of the absent Brothers returned, but among those who had not left their country, one of the greatest was distancing himself imperceptibly from the Pre-Raphaelite ideal. To the applause of the academic world, he was creating a more independent and important place for himself; this was Millais. Each of the others was moving off in the direction that his affinities and his most mature talents pointed out for him. Ruskin noticed Millais’ defection and raised the alarm, but in vain. Ruskin himself had evolved. Thus, the year 1857 is a decisive date in history, like the year 1846. In 1846, Haydon, the head of the Royal Academy School, committed suicide, and Madox Brown had just exhibited his William the Conqueror. In 1857, Madox Brown’s school had triumphed and Millais, the head of that school, committed moral suicide. The entire 1850 movement can be situated between these two dates. In 1846, a man sought to create a new movement but was not yet able to amass an army. In 1857, they had all turned to their own specialisations, like soldiers returning home. The troops were dismissed, for they had nothing more to do: Pre-Raphaelitism was victorious.

John Everett Millais,