A new world order, the future shape of which remains unclear, is being driven by China ’s emergence as a global power. As we saw in the last chapter, the most advanced expression of this process is in East Asia, where, in little more than a couple of decades, China has become the de facto centre of the region, an increasingly important market for every country, the key driver of the new economic arrangements presently taking shape, and the country that all others are increasingly obliged to take account of and accommodate, even if the manner of China’s diplomacy remains determinedly and self-consciously sotto voce. So far the changes wrought by China ’s rise have done little to disturb the calm of global waters, yet their speed and enormity suggest that we have entered an era of profound instability; by way of contrast, the Cold War was characterized by relative predictability combined with exceptional stability.

How will the impact of China ’s economic rise be felt and perceived in ten years’ time? How will China behave twenty years hence when it has established itself as second only to the United States and effectively dominates East Asia? Will China continue to operate within the terms of the established international system, as it has done for the last decade or so, or become the key architect and protagonist of a new one? Will the rise of China plunge the world into a catastrophic environmental and climatic crisis as a fifth of humanity rapidly acquires the living standards previously associated with the West? China certainly does not know the answers, nor does the rest of the world, whose behaviour towards China will be a powerful determinant of how China itself responds. International relations experts are fond of citing the rise of Germany and Japan in the early twentieth century as examples of nations whose new-found power could not be contained within the existing international system and whose ambitions eventually culminated in war. The rise of China will not necessarily result in military conflict — and, for the sake of humanity, we must fervently hope that it does not — but it is a sobering thought that the ramifications of China ’s rise for the world will be incomparably greater than those of Germany and Japan, even accounting for the difference in historical times.

The beginning of the twenty-first century marked the moment when China arrived in the global mind. [1037] Until then, for most of humanity, it had largely been a story of a faraway country about which people knew little. Now, within the space of a handful of years, its influence has become real and tangible, no longer a set of statistics or the preserve of policy-makers, but dramatically impacting on popular consciousness around the world. Television programmes and newspaper articles on China have become commonplace. There were two main drivers of this global moment of China-awareness. First, as China established itself as the workshop of the world, ‘made in China’ goods began to flood global markets, from Wal-Mart in the United States to Jusco in Japan, almost overnight reducing the prices of a growing range of consumer goods, creating the phenomenon known as ‘China prices’. Not surprisingly this engendered a feel-good factor about China ’s rise, albeit tempered by the realization that many companies and jobs were migrating to China to take advantage of the much cheaper costs of manufacturing. Second, China ’s double-digit growth rate fuelled a growing appetite for the world’s commodities, which had the opposite effect — inflationary rather than deflationary — of big and persistent hikes in the prices of most commodities, of which oil was the most visible and dramatic. Unless you were a major commodity-producing nation, this induced a feel-concerned factor, a growing realization that there was a downside to China ’s rise. The impact was, thus, felt in different ways around the world: for commodity producers in Africa and Latin America, it primarily meant higher prices for their exports, thereby stimulating economic growth, combined with cheaper manufactured goods; for the West and Japan it meant a large fall in the prices of consumer products and clothing, then spiralling commodity prices; for East Asia it meant a vast new market for their products and low-priced ‘China goods’ at home. Whatever the precise effect, and for most of the world it has so far been beneficial, China ’s arrival on the world market ushered in a new kind of global awareness of China: it marked the foothills of China ’s emergence as a global power.

In 2001 China officially launched its ‘Going Global’ strategy, which was primarily intended to foster a closer relationship with commodity-producing countries and thereby secure the raw materials the country urgently required for its economic growth. The effects of this policy have been dramatic. In the space of less than a decade, China has forged close ties with many countries in Africa and Latin America, and to a lesser extent the Middle East. The West, understandably, is most interested in and concerned about how China directly impinges upon it, but in fact China ’s changing relationship with the developing world is of rather greater import in China ’s emergence as a nascent global power. China’s overseas investment increased by more than five times between 2000 and 2005, reaching $11.3 billion, and has continued to rise sharply, with East Asia the most important destination (accounting for over half in 2004), and Latin America, Africa and the Middle East of growing importance. [1038] In 2000 President Hu Jintao toured Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Cuba, paving the way for a series of deals which have resulted in much closer economic links. Brazil now exports large quantities of iron ore, soya beans, cotton, timber and zinc to China, Argentina supplies large quantities of soya, Chile is exporting growing quantities of copper, and Venezuela and China have concluded an agreement for the long-term supply of oil. [1039] Until the global downturn in 2008 they were all enjoying a boom on the back of rising commodity prices consequent upon Chinese demand. [1040] By 2010, China could become Latin America’s second largest trading partner: China, in short, is beginning to make its presence felt in the US ’s own backyard. [1041] By far the most dramatic example of China ’s Going Global strategy, however, is Africa.

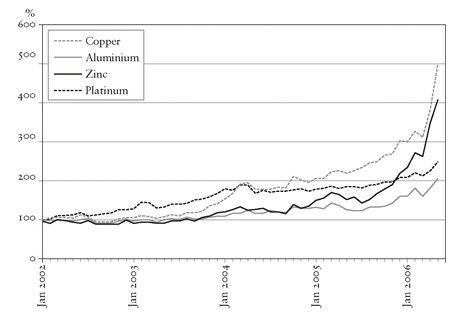

Figure 33. The rising global price of commodities prior to the credit crunch.

AFRICA

The attraction of Africa for China is obvious: it needs a vast range of raw materials to fuel its economic growth. In 2003 China accounted for 7 % of the world’s consumption of crude oil, 25 % of aluminium, 27 % of steel products, 30 % of iron ore, 31 % of coal and 40 % of cement. [1042] As I discussed in Chapter 6, China is very poorly endowed with natural resources and as a consequence has no choice but to look abroad. Africa, on the other hand, is extremely richly endowed with raw materials, and recent discoveries of oil and natural gas have only added to this. Unlike the Middle East, moreover, which continues to receive enormous American attention, Africa has, in recent years, been relatively neglected, having remained of marginal concern to the US. [1043] In 2006 the new relationship between Africa and China was publicly consummated, with Hu Jintao’s tour of African capitals followed in November by heads of state and dignitaries from forty-eight African countries attending the largest summit ever held in Beijing. [1044] The Chinese premier Wen Jiabo proposed that trade between China and Africa should double between 2005 and 2010. The Chinese made a range of other undertakings including doubling its 2006 assistance by 2009; establishing a China-Africa development fund of $5 billion to encourage Chinese companies to invest in Africa and provide support for them; increasing from 190 to over 440 the number of export items to China in receipt of zero-tariff treatment from the least developed countries in Africa; providing $3 billion of preferential loans and $2 billion of preferential buyer’s credits to Africa over the next three years; cancelling debt in the form of all the interest-free government loans that matured at the end of 2005 owed by the most heavily indebted and least developed African countries; and over the next three years training 15,000 African professionals, sending 100 agricultural experts to Africa, building 30 hospitals and 100 rural schools, and increasing the number of Chinese government scholarships to African students from 2,000 per year to 4,000 per annum by 2009. At the conference major deals were signed, including for the development of an aluminium plant in Egypt, a new copper project in Zambia and a mining contract with South Africa. [1045]

[1038] ‘Reaching for a Renaissance: A Special Report on China and Its Region’, The Economist, 31 March 2007, p. 6.

[1039] Ben Schiller, ‘The Axis of Dil: China and Venezuela ’, 2 March 2006, posted on www.open democracy.

[1040] Clyde Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East (New York: Basic Books, 2006), p. 241; Robert F. Noriega, ‘China’s Influence in the Western Hemisphere’, statement before the House Sub-committee on the Western Hemisphere, Washington, DC, 6 April 2005.

[1041] Joshua Kurlantzick, Charm Offensive: How China’s Soft Power is Transforming the World (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007), p. 95.

[1042] Shell, Shell Global Scenarios to 2025: The Future Business Environment — Trends, Trade-offs and Choices (Washington, DC: Institute for International Economics, 2005), p. 129.

[1043] Raymond W. Copson, ‘US Response to China ’s Rise in Africa: Policy and Policy Options’, in Marcel Kitissou, ed., Africa in China’s Global Strategy (London: Adonis and Abbey, 2007), p. 71.