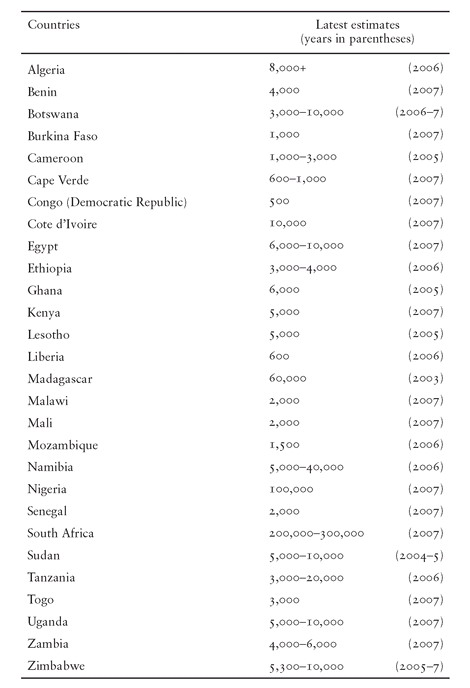

Table 5. Number of Chinese in selected African countries, 2003-7.

The contrasting approach of China and Western nations towards Africa, and developing countries in general, has led to a discussion amongst Africans about a distinctive Chinese model of development, characterized by large-scale, state-led investments in infrastructure and support services, and aid which is less tied to the donor’s economic interests and less overwhelmingly focused on the extraction of minerals as in the case of the West. [1076] China ’s phenomenal growth, together with the huge reduction in poverty there, has also provoked enormous interest in what lessons it might offer for other developing nations. [1077] An important characteristic of the Chinese model has been the idea of strong government and the eschewing of the notion of democracy, an approach which has an obvious appeal amongst the more authoritarian African governments. In the light of the country’s economic success, the Chinese approach to governance seems destined to enjoy a much wider influence and resonance in the developing world. The Chinese academic Zhang Wei-Wei has argued that the Chinese model combines a number of features. In contrast to the Washington Consensus, it rejects shock therapy and the big bang in favour of a process of gradual reform based on working through existing institutions. It is predicated upon a strong developmental state capable of steering and leading the process of reform. It involves a process of selective learning, or cultural borrowing: China has drawn on foreign ideas, including the neo-liberal American model, as well as many that have been home-grown. Finally, it embraces sequencing and priorities, as evidenced, for example, by a commitment to economic reforms first and political ones later, or the priority given to reforms in the coastal provinces before those in the inland provinces. [1078] There has been considerable debate, in this context, about a Chinese model, sometimes described as the Beijing Consensus. There are certainly fundamental differences between the Chinese approach and the Washington Consensus, with the Chinese model both markedly less ideological and also distinctively pragmatic in the manner of the Asian tigers.

It is still far too early to make any considered judgement about the likely long-term merits and demerits of China ’s relationship with Africa. [1079] The experience has been brief and the literature remains thin. The most obvious danger for Africa lies in the fundamental inequality that exists at the heart of their relationship: China’s economy is far bigger and more advanced, the nearest economic challenger, South Africa, being diminutive in comparison, while the population of Africa as a whole is less than that of China’s. The economic disparity between Africa and China, furthermore, seems likely to grow apace. Whatever the differences in approach between the Western powers and China, it seems likely that many of the problems in the relationship between the West and Africa, emanating from the fundamental structural inequality between them, seem likely to be reproduced in some degree in China ’s relationship with Africa. [1080] The danger facing African countries is that they get locked into being mere suppliers of primary commodities, unable for a variety of reasons — including unfavourable terms of trade and Chinese competition, together with domestic corruption and a lack of strategic will — to move beyond this and broaden their economic development through industrialization.

At a conference in Beijing in 2005, Moeletsi Mbeki, deputy chairman of the South African Institute of International Affairs, spelt out these fears:

Africa sells raw materials to China and China sells manufactured products to Africa. This is a dangerous equation that reproduces Africa ’s old relationship with colonial powers. [1081] The equation is not sustainable for a number of reasons. First, Africa needs to preserve its natural resources to use in the future for its own industrialization. Secondly, China ’s export strategy is contributing to the deindustrialization of some middle-income countries… it is in the interests of both Africa and China to find solutions to these strategies. [1082]

Perhaps the country that most exemplifies this inequality is Zimbabwe, where the Chinese enjoy a powerful presence in the economy, controlling key strategic areas like the railways, electricity supply, Air Zimbabwe and the Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation. [1083] The fact that China has a carefully worked-out and comprehensive strategic approach to its relationship with Africa, while the African response, in contrast, is fragmented between the many different nations, poorly informed about China, and based on an essentially pragmatic rather than strategic view, serves only to exacerbate this inequality. [1084] The danger is that African nations enter into agreements with China over the exploitation of their natural resources which are too favourable to China, or use the revenues gained in a short-term fashion, perhaps corruptly, to benefit various interest groups, or possibly both.

Although China ’s presence has been hugely welcomed across the continent, and has generated considerable enthusiasm, [1085] there is also unease and concern. This has been most manifest in Zambia, where in the last presidential election in 2006 the opposition candidate propounded a strongly anti-Chinese line, declaring that ‘Zambia is becoming a province — no, a district — of China’, and gained 29 per cent of the vote, prompting the Chinese ambassador to imply that China might withdraw its investments in the event of his winning. [1086] One of the strongest and most persistent criticisms is that Chinese companies prefer to employ Chinese rather than local workers, with the proportion of Chinese workers sometimes reaching as high as 70 per cent. [1087] There are also frequent complaints that Chinese managers display negative attitudes towards local people. [1088] Both of these, of course, touch directly upon the problem of Chinese attitudes towards those of darker skin, and especially Africans, which I discussed in Chapter 8. The evidence is still too sparse to draw any proper conclusions as yet, though the problem is unsurprising. There is a widely held view, especially in the West, that China ’s refusal to require any conditionality in terms of governance means that it is prone to turn a blind eye to human rights abuses, such as those in Darfur. [1089] That has certainly been the case, but the Chinese have recently shown growing sensitivity towards Western criticism, as well as that from within the continent, and as a result have helped to pressure the Sudanese government into accepting the presence of a joint United Nations/ African Union peacekeeping force in Darfur. [1090] There is little evidence, however, that China ’s record in Africa is any worse — and in fact is almost certainly far better — than the West’s own miserable catalogue of support for corrupt and dictatorial regimes on the continent, not to mention its colonial legacy. [1091] Finally, in a rather different vein, the Chinese have become the target of terrorist groups, for example in the Niger Delta and Ethiopia, a phenomenon which is surely set to grow as the Chinese presence and influence expands and they assume the role, visibility and responsibilities of a global power not only in Africa but elsewhere too. [1092]

[1077] Kaplinsky, ‘Winners and Losers’, pp. 12–13; Marks, introduction in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa, pp. 6–7.

[1078] Zhang Wei-Wei, ‘The Allure of the Chinese Model’, International Herald Tribune, 1 November 2006.

[1079] For an interesting discussion of China ’s involvement in Africa in a broader historical context, see Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, ‘East Mountain Tiger, West Mountain Tiger: China, the West, and “Colonialism” in Africa ’, Maryland Series in Contemporary Asian Studies, 3 (2006).

[1080] Barry Sautman and Yan Hairong, ‘Friends and Interests: China ’s Distinctive Links with Africa ’, African Studies Review, 50:3 (December 2007), p. 78.

[1081] See John Reed, ‘ China ’s Africa Embrace Evokes Imperialist Memories’, Financial Times, 27 September 2006.

[1082] Moeletsi Mbeki, South African Journal of International Affairs, 13(1): 7 (2006), quoted in Marks, introduction in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa, p. 5.

[1084] Rocha, ‘A New Frontier in the Exploitation of Africa’s Natural Resources’, p. 31; Sautman and Yan, ‘Honour and Shame?’, pp. 55-6. Chris Alden argues that ‘at the regional and multilateral levels African reactions to Beijing have been basically lacking in any strategic approach, as well as being fundamentally uncoordinated.’ Alden, China in Africa , p. 77.

[1085] Howard W. French and Lydia Polgreen, ‘ China Brings Its Deep Pockets to Africa’, International Herald Tribune, 13 August 2007; Alden, China in Africa , p. 35.

[1086] Alden, China in Africa, pp. 74-6; Michelle Chan-Fishel, ‘Environmental Impact: More of the Same?’ in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa , p. 144.

[1089] Ali Askouri, ‘China’s Investment in Sudan: Displacing Villages and Destroying Communities’, in Manji and Marks, African Perspectives on China in Africa, pp. 74, 80; Curtis and Hickson, ‘Arming and Alarming?’, p. 41.