It would be wrong to assume that the future will be a simple extrapolation of these recent trends. The precipitous, for example, certainly cannot be excluded, especially in light of the open-ended nature of Sino-Taiwanese relations. Less apocalyptically, the process of change witnessed over the last decade could slow down, or alternatively perhaps accelerate. The United States could try to restrain the momentum and direction of that change by engaging in a more imaginative and proactive strategy towards East Asia under Obama. More speculatively, if relations between China and the US in East Asia should seriously worsen at some point in the future, the United States might seek to contain China. [1033] If this should happen, then it would inevitably have serious ramifications for their global relationship. [1034] But nor can the possibility be excluded that the US will in time become reconciled to its declining influence in East Asia. Should that be the case, there is little evidence so far to suggest that the region will become more unstable as a consequence: on the contrary, during the period that has coincided with China’s rise, East Asia has been, at least hitherto, strikingly conflict-free. Given that East Asia was characterized by long-term historical stability during the tributary period as a result of China ’s overwhelming power, this should not necessarily be regarded as surprising. [1035]

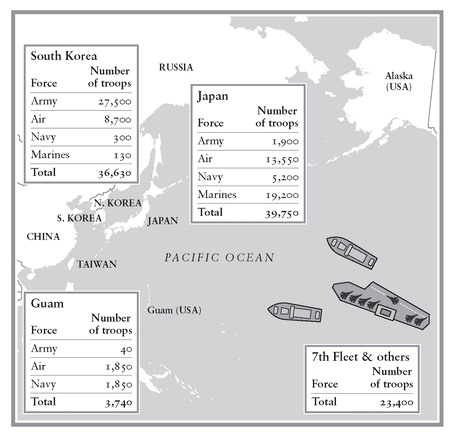

Figure 31. American troops in East Asia 2007.

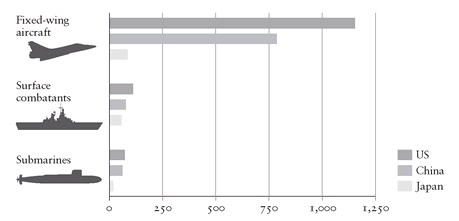

Figure 32. Naval capability, 2007.

As things presently stand, China is already established as the dominant land power in the region, while the United States remains, at least for the medium term, the dominant regional maritime power. [1036] While this naval strength clearly serves to contain China’s power in the region, it is also a sign of the US’s increasing weakness, with land power an expression of China ’s growing economic and political clout and maritime power almost solely a function of the US ’s hard power. Indeed, it would seem that China is not so far away from achieving hegemony within the region in most respects (economic, political and cultural) other than military. By far the most important US ally in East Asia remains Japan, and, a little further afield, Australia is still an American intimate, notwithstanding its closer relationship with China. The US has also been working very hard to try to recruit India to its side. Between them these constitute a formidable counter to China, albeit ringing East Asia rather than, except in the case of Japan, being part of it. Both Russia and India overlap with and abut East Asia, and therefore can also be regarded as significant players in the region, but I will consider their relationship with China’s rise in the next chapter.

10. China as a Rising Global Power

Not far from Renmin University in the north-west of Beijing, there is a gargantuan Carrefour hypermarket which sells everything from clothes and refrigerators to sports equipment and food, and which takes a lifetime just to walk through let alone shop in. It is the largest supermarket I have ever used and throngs with many thousands of Beijingers every day of the week. Carrefour, French-owned and the world’s second largest retailer, has 112 such hypermarkets in China, though they vary considerably in size. In April 2008 Carrefour found itself the target of a protest which spread like wildfire across China, with demonstrations taking place outside stores in Beijing, Wuhan, Heifei, Kunming, Qingdao and many other cities. The origin of the anti-Carrefour campaign was a few brief postings on China ’s internet bulletin boards which claimed that the retailer and one of its shareholders, LVMH, the French luxury group, had financed the Dalai Lama’s government-in-exile in India. Coming hard on the heels of the riots in Tibet, it was an incendiary campaign, which was given added charge by the anger felt towards the protests in Paris against the Olympic torch relay and suggestions that President Sarkozy might boycott the Games. The large crowds that gathered outside many Carrefour hypermarkets urged shoppers to boycott the stores. Demonstrators carried pictures of Jin Jang, a wheelchair-bound Chinese athlete, who had been accosted by a French protester during the torch relay in Paris and whose treatment had incensed the Chinese public. Shoppers who bravely ventured into Carrefour stores did so under the protection of scores of riot police. The eruption of Chinese protests against Carrefour, which threatened to engulf other French companies as well, was reminiscent of those staged against Japanese companies in 2005 when relations between China and Japan reached a new nadir.

Alarmed by the threat to their Chinese operations, Carrefour vehemently denied the rumours about it funding the Tibetan government-in-exile and declared its opposition to the splitting of China. To contain the protests, China ’s internet gatekeepers began restricting searches using the French company’s name. Meanwhile, President Sarkozy sought to defuse anger over the protests in Paris by offering a tacit apology for ‘wounded’ Chinese feelings. With French companies growing increasingly concerned about a boycott of their goods by Chinese consumers, Nicolas Sarkozy wrote a letter to Jin Jang, the Chinese athlete, offering his ‘sympathy’. He acknowledged the ‘bitterness’ felt in China about the French protests and the attack on Jin Jang, referring to it as a ‘painful moment’ which he condemned ‘in the strongest possible terms’. ‘I must assure you,’ he continued, ‘that the incidents on that sad day, provoked by certain people, do not reflect the feelings of my fellow citizens for the Chinese people.’ The letter was handed to Jin Jang in person by the head of the French Senate during an official visit to Shanghai. Mr Sarkozy also sent his chief diplomatic advisor to Beijing in an effort to calm feelings.

Earlier that year another French company, Peugeot Citroën, found itself on the wrong end of Chinese public opinion when it carried an advert in the Spanish newspaper El Pais featuring a computer-modified Mao Zedong scowling down from an advertising hoarding at a Citroën car. At the bottom of the ad was the slogan: ‘It’s true, we are leaders, but at Citroën the revolution never stops.’ The ad was attacked on Chinese internet bulletin boards for ‘hurting our national pride’ and ‘damaging the whole Chinese people’. It was hastily withdrawn by the company, which described the ad as ‘inappropriate’ and expressed regret for any ‘displeasure’ caused. Its statement read: ‘We repeat our good feelings towards the Chinese people, and confirm that we respect the representatives and symbols of the country.’ Then in May, Christian Dior, the French fashion brand, became the latest global company to learn the hard way about the danger of offending Chinese sensibilities. Facing the prospect of a boycott of its products, the company dropped the American actress Sha ron Stone from its advertising in China after she suggested that the recent earthquake in Sichuan province was karmic retribution for how Beijing had treated Tibet. In the same month the Dalai Lama collected an honorary doctorate from the London Metropolitan University, which attracted considerable criticism in the Chinese media. In June the university’s vice-chancellor met with officials at the Chinese embassy and ‘expressed regret at any unhappiness that had been caused to Chinese people by the recent award’. It was widely believed that the apology was not unconnected with the fact that 434 students from China were currently studying at the university and that Chinese students have become an extremely lucrative source of revenue for British universities. In their different ways these examples testify to the importance of the Chinese market for many foreign companies and universities, and the extent to which foreign political leaders are prepared to bow to Chinese sensitivities. They underline the growing influence on the global stage of Chinese public opinion, concerns and attitudes.