At times of crisis, the Chinese government has tried hard to restrain popular attitudes of resentment towards Japan for fear that they might get out of control; sometimes, however, they have spilt over, as was the case with the large and angry demonstrations that took place in several Chinese cities in 2005. While Taiwan and the United States have been important factors in Chinese nationalism, especially in the 1990s, its growth has been driven, above all, by feelings of resentment and hostility towards Japan. These remain much stronger than the enmity displayed towards the United States. [1016] Apart from the Korean War, there is no history of conflict between China and the US. Moreover, the two countries succeeded in 1971 in remaking their relationship and putting it on an entirely new footing that has survived to the present day. They are also, of course, geographically separated by the expanse of the Pacific Ocean. In contrast, the bitter enmity between the Japanese and Chinese has existed for over a century without interruption. There is simply no modern tradition of compromise or coexistence between them and yet they are by far the two most powerful countries in East Asia. [1017] The Chinese may not particularly like the Americans but they generally respect them; in contrast, as I have frequently found, the Chinese — including the highly educated — will often volunteer that they hate the Japanese. [1018] The rise of China, moreover, has if anything served to harden attitudes towards Japan. As Shi Yinhong has observed, the view is now widely expressed that: ‘If China concedes to Japan it means that China cannot rise. What is the point of rising if we have to concede to Japan?’ [1019] It is, nonetheless, strongly in China ’s interests to play for time. Notwithstanding that Japan remains East Asia’s largest economy (according to GDP by market exchange rates) and by far its most advanced, time, as always it would seem, is on China’s side. Assuming that China continues to grow at a brisk pace, the balance of power between the two will continue to move in China’s favour, [1020] with the latter steadily emerging as the fulcrum of the East Asian economy. [1021] Even for Japan, China is now of great economic significance: it became Japan’s largest export market in 2008, overtaking the United States, with the value of Japanese exports to China doubling between 2000 and 2003, [1022] and it has also become an important manufacturing base for many Japanese multinationals. Japan, in short, is being drawn into a relationship of growing economic interdependence with China. But this does not mean that relations between the two countries will inevitably grow more harmonious: the underlying antagonism between them is far too deeply rooted for that.

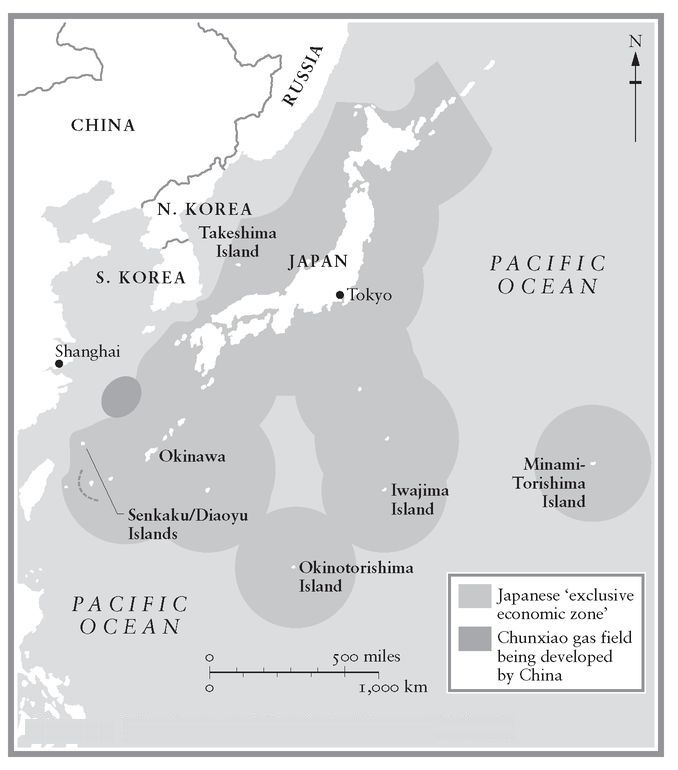

Map 12. The Disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands

So how is the relationship between China and Japan likely to evolve? There are several possible scenarios. [1023] Hitherto, Japan has essentially regarded itself as different, and apart, from the region. As we have seen, that has been the case ever since the Meiji Restoration, with Japan looking up to the West and down on Asia. The fact that this mindset has been a fundamental characteristic of Japan ever since 1868 makes the task of changing it even more difficult and daunting. [1024] Since its defeat in the Second World War, Japan’s detachment from Asia has been reinforced by its military dependence on the United States, with the American defence guarantee obliging Japan to look east across the Pacific Ocean rather than west to its own continent, thereby encouraging it to think of itself as an Asia- Pacific rather than East Asian power. This is illustrated by the fact that in 2007 it concluded a security pact — its only other being with the United States — with Australia, the US’s closest ally in the Asia-Pacific region. Though both unstated and denied, the obvious target of the agreement is China. [1025] Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the terms of its security and defence arrangement with the United States have been significantly strengthened over the last decade. [1026] The most likely scenario is that Japan continues along this same path. For the Japanese it has the great advantage of enabling them to carry on with the status quo and postponing the day when they are required to engage in a fundamental rethink — by far the biggest since 1868 — of their relationship with China in particular and East Asia in general. In China ’s eyes, however, the US-Japan alliance is only the second worst solution, the worst — such are China ’s fears of Japanese history — being a Japan that increasingly aspires to become a military force in its own right. [1027] The latter process is also under way, but it is taking place slowly and within the context of Japan ’s alliance with the United States, rather than separately from it. In the long run, however, dependence on the United States may be unsustainable. The growing economic, political and military strength of China could at some point oblige the Japanese to rethink their attitude towards China in a more positive way, while the United States may also be persuaded at some stage that its relationship with China is rather more important than that with Japan and that its alliance with Japan should effectively be downgraded, shelved or abandoned. But any such outcome, should it ever happen, still lies far in the future. [1028] The one scenario that seems inconceivable is that Japan emerges as a stand-alone superpower to rival China: it is simply too small, too particularistic, too isolated and too weakly endowed with natural resources to be able to achieve this. [1029]

… AND THE ELEPHANT

The elephant in the room or, more precisely the region, is the United States. The latter is not even vaguely part of East Asia, being situated thousands of miles to its east, but with its military alliance with Japan, its military bases in South Korea and its long-term support for Taiwan, not to mention the Korean and Vietnamese wars, it has been the dominant power in the region ever since it replaced Europe in the 1950s. That state of affairs, however, has begun to change with remarkable speed. A combination of 9/11 and the new turn in Chinese foreign policy in East Asia, together with China’s emergence as the fulcrum of the regional economy — one of those accidental juxtapositions of history — has transformed Chinese influence in the region, while that of the United States, hugely preoccupied with the Middle East to the virtual exclusion of all else, it would seem, declined sharply during the Bush presidency. [1030] Given that the period involved has been less than a decade, the shift in the balance of power in the region has been dramatic. In a few short years, every single country has been obliged to rethink its attitude towards China and in every case — excepting Japan and Taiwan (though, since the election of Ma Ying-jeou as president, perhaps even there too) — has moved appreciably closer to it, including Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand and South Korea, all of which have formal bilateral alliances with the United States. [1031] China ’s star in the region is patently on the rise and that of the United States on the wane. [1032]

[1017] Satoh, The Odd Couple; Hirano So, ‘Study of Contemporary Political History of East Asian Region — from the Chain Effect of Chinese and Japanese Nationalism Perspective’, workshop on Sino-Japanese relations, Renmin-Aichi University conference, Beijing, 8 December 2005.

[1018] Gries, China’s New Nationalism, pp. 38, 40; interview with Shi Yinhong, Beijing, 26 August 2005.

[1020] Perhaps this is the underlying reason for China ’s more self-confident stance in its relationship with Japan, as evinced by Hu Jintao. Kokubun Ryosei, ‘Did the Ice Melt between Japan and China?’, conference on ‘Nationalism and Globalisation in North-East Asia’, Asia Research Centre, London School of Economics, 12 May 2007, pp. 1, 9, 11–12.

[1022] Michiyo Nakamoto, ‘China Ousts US as Top Japanese Market’, Financial Times, 21 August 2008; www.rieti.go.jp/en/columns/a01_0109.html.

[1023] For a different and optimistic view of their future relationship, based on demographic trends, see Howard W. French, ‘For Old Rivals, a Chance at a Grand New Bargain’, International Herald Tribune, 9 February 2007.

[1024] Martin Jacques, ‘Where is Japan?’, seminar paper presented at the Faculty of Media and Communications, Aichi University, 27 July 2005; Martin Jacques, ‘The Age of America or the Rise of the East: The Story of the 21st Century’, Aichi University Journal of International Affairs, 127 (March 2006), pp. 7–8.

[1026] Drifte, Japan’s Security Relations with China since 1989, pp. 88–99; Thomas J. Christensen, ‘China, the US- Japan Alliance, and the Security Dilemma in East Asia’, in Brown et al., The Rise of China, pp. 148-9.

[1027] Christensen, ‘ China, the US — Japan Alliance, and the Security Dilemma in East Asia ’, p. 138.

[1030] Interview with Shi Yinhong, Beijing, 19 May 2006; Strait Times, 6 February 2006; Jane Perlez, ‘As US Influence Wanes, a New Asian Community’, International Herald Tribune, 4 November 2004.