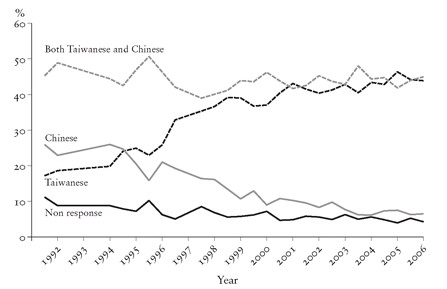

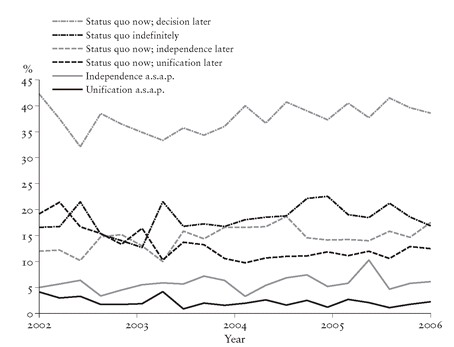

A key question here concerns the nature of Taiwanese identity. To what extent is it constituted as different from and in opposition to Chinese identity? And is a sense of Taiwanese identity positively correlated with support for Taiwanese nationalism and ultimately independence? As can be seen from Figure 29, between 1992 and 2006 the proportion of Taiwanese who thought of themselves simply as Chinese has been steadily declining, while those who felt themselves to be Taiwanese has been commensurately rising. However, the group that consider themselves to be both Taiwanese and Chinese has been consistently large — by a narrow margin, in fact, the biggest of all — accounting for almost half the electorate. The picture is, therefore, rather complex. The fact that the largest group consider themselves to be both Taiwanese and Chinese suggests that the two identities, far from being mutually exclusive, are seen by almost half the population as complementary. Many, in fact, recognize that their Taiwanese identity, based on a shared sense of history, culture, place and customs, exists within and alongside their sense of being Chinese. [971] This would suggest that there is not necessarily a strong correlation between a sense of Taiwanese identity and support for independence. This is rather borne out in Figure 30. The largest group supports the status quo, with any decision on the island’s status to be postponed until later, or what might be described as a ‘wait and see’ position. The second largest group (which enjoys half the support of the former) favours the status quo now and independence later, but this is more or less matched by those who prefer the status quo indefinitely. And not far behind this group in terms of support are those who favour the status quo and unification with China later; there is minimal backing, though, for immediate unification. Only a small minority support immediate independence, and this group combined with those who favour the status quo and independence later comprise less than a quarter of the population. Furthermore, the combined support for these two positions peaked in 1999 and has subsequently levelled off or even declined slightly.

Figure 29. Changing Taiwanese attitudes towards Taiwanese/Chinese identity.

Figure 30. Taiwanese support for unification and for independence.

This suggests that Taiwanese identity is a diverse and malleable concept which means different things to different people. It does not appear to have a strong political content, otherwise there would be a closer correlation between Taiwanese identity and support for independence. [972] Rather than seeing the direction of Taiwan as predetermined, the situation is, in fact, fluid and open-ended. Taiwanese opinion is open to influence according to the way in which China behaves and the exigencies of Taiwanese politics, together with deeper underlying trends, including how China evolves economically and politically in the longer run, what happens to the Taiwanese economy, and the impact of economic integration between China and Taiwan.

While there is nothing inevitable about the political effects of growing economic integration, the sheer speed and extent of the process over the last few years has had a major impact on Taiwanese politics. Fear of its consequences persuaded former president Lee Teng-hui to impose restrictions on investment in China by Taiwanese companies and to hasten the process of Taiwanization in order to take advantage of what Lee saw as a window of opportunity before the dynamic of economic integration began to close down options. [973] Chen followed suit, though he was forced to bow to pressure from Taiwanese companies and ease some of the restrictions. The growing dependence of Taiwanese companies both on the Chinese market and on their manufacturing operations in China has become an influential consideration in the minds of both Taiwanese business and the Taiwanese electorate. Whereas once the country was largely dependent on the American market, this has been supplanted in importance by the Chinese market in a manner similar to China ’s other neighbours. In Taiwan’s case, though, this process has happened even more quickly and gone a lot further — primarily, no doubt, because of shared Chinese customs, culture and language, though other factors like geographical proximity are also significant. Any calculation concerning Taiwan ’s economic future, or the prospects for living standards, must inevitably place China at the centre of the equation. It is hardly surprising that in a 2005 survey almost twice as many Taiwanese were in favour of strengthening economic ties between China and Taiwan as compared with those in favour of downgrading them. [974] And China has recently sought to use these growing connections to build links with different sections of the Taiwanese population in order to influence the political climate and place political pressure on the Taiwanese government. [975]

The manifest volatility of Taiwanese public opinion has underlined the need for China to court and influence it, yet this is a matter to which the Chinese government has historically attached relatively little importance. There are three reasons for this. First, the Chinese concept of the ‘lost territories’ means that Taiwan, as in the case of Hong Kong, is seen in terms of an historic claim rather than popular sovereignty: in other words, legitimacy is regarded as a matter of history rather than the present. As a consequence of this attitude, the Hong Kong people were not represented in the talks about the handover, which were conducted exclusively between the Chinese and the British. [976] This differed from what has normally happened in negotiations over decolonization, with those seeking independence from the colonial power generally represented at the conference table. Second, the Chinese attitude towards both Hong Kong and Taiwan demonstrates the overriding importance attached to state sovereignty and the absence of any tradition of popular sovereignty, a subject I discussed in Chapter 7. Third, the Chinese view of Taiwan involves a particular concept of Chineseness, which conceives of it in essentialist terms, as immutable, timeless and fixed in history, something that is inherited at birth, whether one likes it or not. This is directly related to the discussion in the last chapter about the nature of the Han Chinese, who are seen by the Chinese government as homogeneous, even though in reality the Han are a very diverse group. It follows, therefore, that the notion of a Taiwanese identity that serves to supersede or elide one’s Chinese belonging is given little or no credence. [977]

As a consequence the Chinese government, at least until recently, has made little attempt to woo Taiwanese opinion. Indeed, it has often acted in a way that served to inflame, alienate, intimidate and antagonize the Taiwanese — issuing thinly veiled threats, refusing to countenance their views, and resorting to coercive action, most notably the firing of missiles into the Taiwan Strait during the 1996 presidential election campaign. [978] Recently, however, China has been more prepared to engage with the situation in Taiwan as it actually is and thereby take Taiwanese opinion more seriously. [979] This was illustrated by its wooing of the KMT leadership in the period prior to the 2008 parliamentary and presidential elections, including the visit of the former KMT leader Lien Chan to Beijing in 2005. There is now growing optimism in Beijing based on the fact that support for Taiwanese independence seems to have peaked and a view that the majority of Taiwanese are basically pragmatic — supporting, in one form or another, the status quo. The rising economic interdependence between China and Taiwan also points in the direction of the status quo or closer political ties.

[972] Chu Yun-han, ‘The Political Economy of Taiwan’s Identity Crisis’, p. 7; Bush, ‘Taiwan Faces China’, pp. 179-80.