ECHOES OF THE PAST

In the light of the region’s realignment towards China, we can now return to the question of how East Asia’s relationship with China is likely to evolve and, in particular, to what extent it might bear some of the hallmarks of the tributary system. The tributary system and Westphalian system are often regarded as polar opposites and mutually exclusive, the former involving a hierarchical relationship, the latter based on relations of equality between sovereign nation-states. In fact, as mentioned in Chapter 7, the Westphalian system in practice has never been quite that simple. For most of its history it was largely confined to a group of European states, since until the second half of the twentieth century the great majority of countries in the world did not enjoy independence, let alone equality. [937] Even after these countries became sovereign nation-states, in the great majority of cases they were to enjoy nothing like equality with the United States or the West European nations, a situation which was exacerbated during the Cold War, when nation-states experienced what was, in practice, limited sovereignty in their relationship with the superpower to which they owed their allegiance. Life has not been that dissimilar in the era of the single superpower, with most countries enjoying varying degrees of limited sovereignty in their relationship with the United States. Given the profound inequalities in interstate relations, the concept of equality in the Westphalian system is thus legalistic rather than real. In practice, as with the tributary system, it has strong hierarchical features. [938] Like the tributary system, the Westphalian system also has an influential cultural component, namely the idea of hegemony or soft power. In other words, the distinction between the tributary and Westphalian systems is not quite as clear-cut as one might think. Seen in these terms, the restoration of elements of the tributary system in a modernized form does not seem so far-fetched. Some of the old building blocks, moreover, remain firmly in place. Chinese culture not only continues to enjoy great prestige throughout East Asia, but its influence is once again on the rise, helped by the presence of a much larger Chinese minority than existed in earlier times, especially in South-East Asia. Furthermore, in North-East Asia, and also Vietnam, Confucianism is a shared heritage in a not dissimilar way to the role of the Graeco-Roman tradition in Europe.

Historically, the tributary system was the international concomitant of China ’s identity and existence as a civilization-state. And just as the influence of the civilization-state remains palpable in the domestic sphere, so the persistence of the tributary state is apparent in the realm of international relations. In important respects, indeed, Chinese attitudes towards concepts of sovereignty and interstate relations continue to owe at least as much to the tributary legacy as to the contemporary Westphalian system. [939]

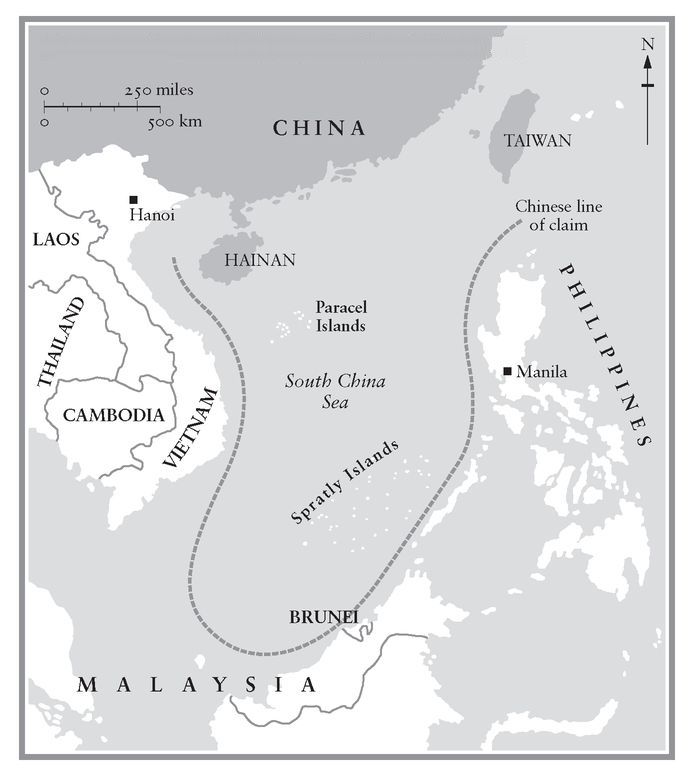

The Chinese concept of sovereignty differs markedly from that in Western-inspired international law. Take the dispute over the sovereignty of the Spratly and Paracel islands, which, though shelved for now — following the agreement with ASEAN — remains, in the long term, unresolved. [940] The Spratly and Paracel islands are barely islands at all, but a collection of uninhabited rocks, many of which are usually under water, situated in the South China Sea, the Spratlys to the north of East Malaysia and to the west of the Philippines, and the Paracels to the east of Vietnam. The idea of maritime sovereignty is a relatively recent innovation, dating from 1945 when the United States declared that it intended to exercise sovereignty over its territorial waters, [941] and it is this body of law that essentially forms the basis of the claim by the various South-East Asian states to the Spratlys and Paracels. China, in contrast, rests its argument on ‘historic claims’, namely that the islands have for thousands of years formed an integral part of the south-east frontier of the Middle Kingdom in the same manner, for example, as the land border to the north of Beijing. Expeditions to the islands have discovered various Chinese artefacts, such as chinaware and copper cash from the Tang and Song dynasties, that have been used to buttress these ‘historic claims’ and demonstrate that the islands have long been a part of China. The islands are part of the folklore of Chinese culture, kept alive, in various invocations of the Chinese frontier spirit, by articles written by Chinese journalists who regularly visit the islands. They are shown on many Chinese maps as clearly within the ‘historic claim line’ (see map on p. 293) and therefore as part of China. [942] Hainan Island, off the southern coast of China, may be China’s smallest land province, but it is also regarded — because of the extent of its maritime territory which, as claimed, reaches far into the South China Sea — as its largest ‘ocean province’. [943] In 2007 Beijing established the new Sansha municipality in Hainan Province, which has jurisdiction over three islets that Vietnam claims in the Spratly and Paracel archipelagos. This led to large-scale protest demonstrations outside the Chinese embassy in Hanoi. [944] The idea of ‘historic claims’ finds expression in the Chinese use of intertemporal law, which concerns rights or wrongs in the historical past. Chinese legal scholars argue that: ‘a judicial fact must be appreciated in the light of the laws contemporary with it, rather than the laws in force at the time when a dispute arises.’ [945] This gives force and legitimacy to history rather than the present, to the laws that prevailed during the era of the tributary system rather than the present international legal system.

Map 11. Chinese Claims in the South China Sea

In 1984 Deng Xiaoping suggested ‘the possibility of resolving certain territorial disputes by having the countries concerned jointly develop the disputed areas before discussing the question of sovereignty’. [946] In other words, the question of sovereignty should not necessarily delay moving forward on other issues. Deng’s remark has frequently been cited by Chinese sources in the context of the islands in the South China Sea, where his approach has in practice been followed, and in relation to the Diaoyu/Senkaku islands in the East China Sea that are disputed with Japan; it has also been suggested in connection with Taiwan. [947] While insisting on their ultimate sovereignty over the latter, the Chinese have offered to shelve the matter more or less indefinitely, providing Taiwan does not seek to declare independence, illustrating the flexibility with which the Chinese are prepared to approach the issue. Alternatively, they have suggested that, providing their sovereignty over the island is accepted by the Taiwanese, Taiwan can continue to have its own government, political system and even armed forces. [948]

[938] For an interesting discussion of these issues, see Wang Gungwu, ‘Early Ming Relations with Southeast Asia: A Background Essay’, in Fairbank, The Chinese World Order, pp. 60–62. Also Park, ‘ Small States and the Search for Sovereignty in Sinocentric Asia’, p. 3.

[940] It should be noted that the Chinese continue to insist that negotiations over the sovereignty of the islands must be conducted on a bilateral rather than a multilateral basis, another echo of the tributary system; Callahan, Contingent States, pp. 97- 8.

[943] Ibid., pp. 33, 66- 7, 78, 83. The Chinese claim the Senkaku/Diaoyu islands in the East China Sea on the same basis; Erica Strecker Downs and Phillip C. Sanders, ‘Legitimacy and the Limits of Nationalism: China and the Diaoyu Islands’, in Michael Brown et al., eds, The Rise of China (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000), p. 51; also Callahan, Contingent States, p. 72.

[944] Willy Lam, ‘ China Flexes Its New Muscle’, International Herald Tribune, 21 December 2007.