If ASEAN has provided the canvas, it is the diplomatic involvement and initiative of China that has actually redrawn the East Asian landscape. In effect, China has been searching out ways in which it might emerge as the regional leader. [893] Underpinning its growing influence has been the transformation in its economic power. This has been the real driver of change in East Asia, the force that is reconfiguring the region. Unlike the European Union, where economic integration followed politics, in East Asia economics has been the dynamo of change, with political change following in its wake. [894] In North-East Asia, intra-regional trade — even in the absence of formally binding agreements — now accounts for 52 per cent of the total trade of the five economies (China, Japan, Taiwan and the two Koreas), a situation that has been achieved in little more than a decade; the equivalent figure for the European Union is 60 per cent, which it took half a century to reach. [895] Between 1991 and 2001, world trade increased by 177 per cent, whereas intra-regional trade in East Asia, despite the Asian financial crisis, increased by a staggering 304 per cent. By far the most important reason has been the growth of China, whose share in intra-regional trade almost doubled between 1990 and 2002. [896] With the emergence of the first Asian tigers in the early sixties, followed by the later examples, including China itself, the East Asian economy used to be seen in terms of ‘flying geese’, with Japan in the lead and the others flying in formation behind. [897] But with China ’s economic rise during the 1990s, Japan ’s role as the most important economy in the region is rapidly being challenged by China. Between 1980 and 2002, while China’s share of East Asian exports increased from 6 per cent to 25 per cent, Japan’s fell from 50 per cent to below 30 per cent; similarly, while China’s share of East Asian imports over the same period increased from 8 per cent to 21 per cent, Japan’s fell from 48 per cent to 27 per cent. [898] Even at the peak of its economic power, Japan’s role was always limited by the fact that it steadfastly refused to open up its economy to exports from its neighbours (other than those from its own foreign subsidiaries) — or, indeed, to the rest of the world — so its influence was largely exercised by a combination of its own foreign direct investment in Japanese overseas subsidiaries, imports from those Japanese subsidiaries and Japanese exports to the region. In contrast China ’s influence, because it has chosen to have an extremely open economy, is far more multifarious — as a market for the products of the region, as an exporter and as a multifaceted investor.

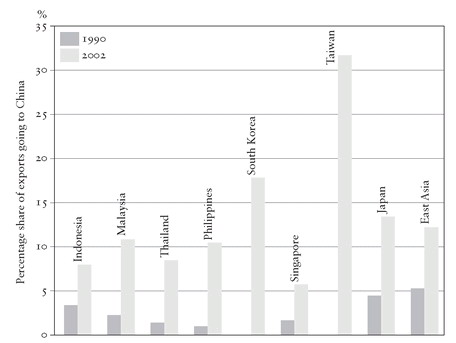

Figure 24. Growing importance of Chinese market.

Zhang Yunling, one of the architects of China ’s new strategy, and Tang Shiping have described the aim as: ‘to make China a locomotive for regional growth by serving as a market for regional states and a provider of investment and technology’. [899] The most obvious expression of this has been the way in which, in less than a decade, China has become one of — if not the — most important market for many countries in the region: in a few years’ time, it seems likely that it will be the single largest market for every country in the region. For the ASEAN countries, the Chinese market is now three times the size of Japan ’s. [900] No country — not even Japan, whose trade with China has recently overtaken that with the United States — can afford to ignore the Chinese market, or, as a consequence, China. [901] Since 200 °China ’s imports from ASEAN have increased at an annual rate of 30–40 per cent. [902] China, for example, accounted for 13.2 per cent of Singapore ’s exports in 2001, compared with 2.5 per cent in 1993, 18.5 per cent of South Korea ’s exports in 2001, compared with 6 per cent in 1993, and 9.2 per cent of Australia ’s exports in 2000, compared with 6 per cent in 1994. [903] It was widely feared in South-East Asia that Chinese imports from the ASEAN countries would be overwhelmingly comprised of raw materials. Certainly these are very significant, a case in point being the huge Chinese demand for timber, which is rapidly stripping the Indonesian forests. [904] The most important single category of ASEAN exports to China, however, is composed of intermediate goods. China is where the final assembly of many products of foreign-owned multinationals (American, European, Japanese, Taiwanese and South Korean) takes place prior to their export to their final destination. Countries like Malaysia and Thailand thus occupy a crucial niche in a complex division of labour centred on China. [905] In addition, China is assuming the role of an increasingly important investor in the region, with a large quantity of investment aimed at the extractive industries and infrastructure like railways, toll roads and refineries, in order to speed the flow of natural resources to the Chinese market. In 2002, 60 per cent of China ’s total foreign direct investment was directed towards Asia, [906] making it by far the most important destination. As a consequence, Chinese investment in South-East Asia has helped to compensate for the decline in Western investment over the last few years.

Zhang Yunling and Tang Shiping have described China ’s regional strategy in the following terms: ‘participate actively, demonstrate restraint, offer reassurance, open markets, foster interdependence, create common interests, and reduce conflict’. [907] With one bold and unexpected stroke, China has succeeded, in the manner of Deng Xiaoping, in redefining the dynamics of the region and, in the process, given itself more space for its own economic development. For sheer courage and unpredictability, China ’s East Asian initiative belongs to the genre of Chinese diplomacy initiated by Mao in the rapprochement with the United States in 1971. Even the intractable problems of North-East Asia are to some extent being redrawn by the ASEAN-BASED Chinese initiative, with both Japan and South Korea now involved in the creation of the East Asian Free Trade Area first proposed by the Chinese premier Wen Jiabao at the 2003 ASEAN+3 summit. It is impossible to predict the outcome of the process — or, more accurately, processes — now under way. They are open-ended and multi-layered, and could yet acquire another dimension, with the involvement of India and perhaps other South Asian countries in the future. [908] It has been suggested that one day there might be a fully-fledged East Asia Economic Union, perhaps even with a common currency, although the latter seems fanciful given the huge economic disparities across the region. [909] Nonetheless, the renminbi is likely to play a growing role in the region, especially if China further eases the restrictions on its use, as is likely over the next five years or so. In that eventuality, and assuming the dollar declines, the renminbi will increasingly be used for trading purposes, other countries in the region will peg their currencies to it, and in time it will surely assume the role of the reserve currency of choice in the region. [910] It is worth noting that in the zones around China’s borders — Myanmar, Mongolia, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam — the renminbi, though not yet convertible, is already traded freely and used as a de facto reserve currency, sometimes instead of theUSdollar. [911]

[894] Zhu Feng, ‘Regionalism, Nationalism and China’s Regional Activism in East Asia’, unpublished paper, 2006, p. 4; and Takashi Inoguchi, ‘Nationalism, Globalisation and Regional Order in North-East Asia: The Case of Japan at the Dawn of the Century’, paper presented at conference on ‘Nationalism and Globalisation in North-East Asia’, Asia Research Centre, London School of Economics, 12 May 2007,

[896] Hideo Ohashi, ‘China’s Regional Trade and Investment Profile’, in Shambaugh, Power Shift, p. 72; Guillaume Gaulier, Françoise Lemoine, Deniz Ünal-Kesenci, ‘China’s Integration in East Asia: Production Sharing, FDI and High-Tech Trade’, CEPII Working Paper No. 2005-09, pp. 35- 6.

[897] Wang Zhengyi, ‘Contending Regional Identity in East Asia: ASEAN Way and Its Implications’, unpublished paper, 2001, pp. 12–15. World Bank, The East Asian Miracle: Economic Growth and Public Policy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), Chapters 1, 4.

[904] Jane Perlez, ‘Forests in Southeast Asia Fall to Prosperity’s Ax’, New York Times, 29 April 2006; ‘ China and the East Asia Survey’, The Economist, 5 May 2007.

[905] Zhang and Tang, ‘ China ’s Regional Strategy’, p. 62; and Ohashi, ‘ China ’s Regional Trade and Investment Profile’, p. 76.