Not surprisingly, China ’s rapidly developing economic influence in the region is having wider political and cultural repercussions. [912] Everywhere, in varying degrees, the impact of China can be felt. The willingness of China to foster interdependence, to seek new arrangements, and to take into account the needs and interests of other nations has had an extremely favourable effect on how it is seen in most countries. [913] David Shambaugh, a leading US writer on China, argues: ‘Bilaterally and multilaterally, Beijing ’s diplomacy has been remarkably adept and nuanced, earning praise around the region. As a result, most nations in the region now see China as a good neighbor, a constructive partner, a careful listener, and a non-threatening regional power.’ This process has been enhanced by the stark contrast over the last decade between China ’s whole-hearted embrace of multilateralism and the United States ’ preoccupation with the Middle East combined with its shift towards unilateralism during the Bush administration. China’s overseas aid has risen from around $260 million in 1993 to more than $1.5 billion in 2004 at a time when the US has been reducing its own; as a result, China’s aid to the Philippines is now four times that of the US, double what the US gives to Indonesia, and far outstrips American aid to Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar. [915] China is funding many high-profile projects, including a new presidential palace and foreign ministry building in East Timor and a parliament building in Cambodia. [916] It finances the training of Cambodian and Laotian officials in China as well as receiving a growing number of politicians and dignitaries from the region in China on visitor programmes. [917] It has opened its doors to foreign students, with over 60,000 from East Asia studying for advanced degrees in Chinese universities in 2003-4. [918] There is a growing thirst across the region to learn Mandarin, while Chinese tourists are becoming an increasingly common sight in South-East Asia, greatly outnumbering those from Japan.

SHIFTING SANDS

One of the consequences of China ’s growing economic importance has been that the great majority of countries in the region have become more closely aligned with it. There are only two exceptions to this: Taiwan, at least until recently, and Japan. Even Singapore and the Philippines, two traditionally close allies of the United States, have moved much closer to China. Rather than countries fearing the rise of China and, as a result, choosing to move closer to the United States, the opposite has happened. Nor has there been any sign of an arms race in the region. A senior Singaporean diplomat confidentially offered the view in 2004 that:

The balance of influence is shifting against the United States. In the last decade the Chinese have not done anything wrong in South-East Asia. The Japanese have not done anything right, and the US has been indifferent. So already Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, and other states are defining their national interest as ‘Finlandization’ with respect to China. The US will never be shut out of South-East Asia completely, but there is less room for it now than in the past fifty years. [919]

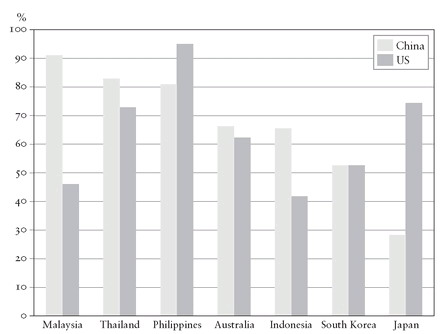

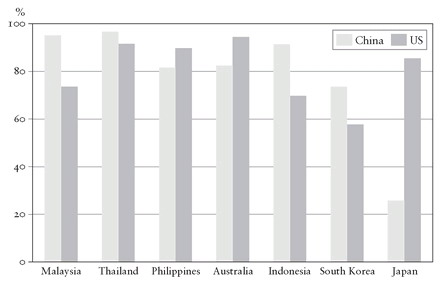

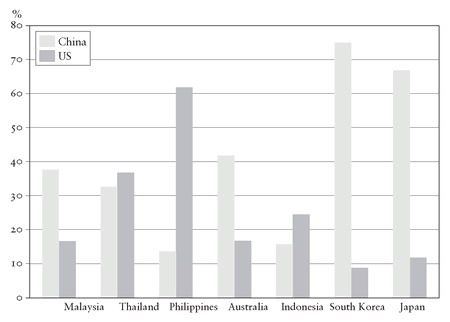

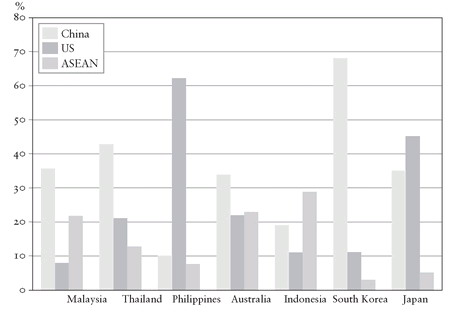

As the accompanying figures suggest, attitudes in the region have grown more favourable towards China, compared with those towards the US, while China is generally seen as emerging as the new power centre in the region and as likely to become the most important economic partner of most countries. To illustrate the reconfiguration of power in East Asia towards China, I will look at three very different examples, namely Myanmar, Malaysia and South Korea; and then at the remarkable way in which Australia is being drawn into China ’s orbit.

As a former tributary state of the Middle Kingdom, Myanmar has long enjoyed a close relationship with China, but since the late eighties this has become more marked. The growing isolation of Myanmar — especially from and by the West — has served to increase its dependence on China for both trade and security, with the latter now by far its biggest trading partner as well as its largest source of inward investment. The country’s Chinese minority, which has grown considerably in recent years, has played a very important role in this growing economic alignment with China. There is also close military collaboration between the two countries, the only such instance of this in the region (with the partial exception of North Korea). With their long shared border, Myanmar is an important ally for China because it gives its landlocked south-west provinces vital access to the Indian Ocean for their exports while also providing a base for the Chinese navy to operate in the Indian Ocean. For a combination of historical and economic reasons — and because otherwise Myanmar would find itself even more isolated — China’s relationship with Myanmar is, in fact, more intimate than that with any other country in the region. [920]

Figure 25. East Asian attitudes towards China and the United States (% ‘favourable’) Nov 2005.

Figure 26. East Asian perceptions of bilateral relationship with China and the United States (% ‘good’) Nov 2005.

Figure 27. East Asia’s perceptions of Asia’s future power centre (%) Nov 2005.

Figure 28. East Asia’s perceptions of their closest economic partner in 5-10 years (%) Nov 2005.

For geographical reasons, the archipelagic countries of South-East Asia have traditionally enjoyed a more distant relationship with China than those like Myanmar and Vietnam that share the same land mass. [921] Furthermore, the ethnic, cultural and religious differences between China and countries like Malaysia and Indonesia are very pronounced. Malaysia, following its independence in 1957, viewed China with considerable suspicion because of its own large Chinese minority and the fact that the Maoist regime encouraged a guerrilla war, mainly based amongst the local Chinese, against the British and, after independence, against the newly installed Malay-dominated government. With China ’s rapid economic growth during the reform period, together with its turn away from promoting revolutionary change elsewhere, relations steadily improved. Although the two countries were in conflict over the Spratly Islands, the then Malaysian premier Mahathir Mohamed chose to pursue a policy of engagement with China, aware that his country could not win any naval clash. [922] He also played a critical role for more than a decade in encouraging China to become more involved in the region and with ASEAN in particular.

In the longer run any deepening relationship with China is likely to have an effect on the delicate racial balance in Malaysia between the Malay majority and the Chinese minority, who presently account for more than a quarter of the population. Not surprisingly, it is the Chinese minority who are primarily involved in trade with China, who fill the planes that fly between the two countries, and who benefit the most economically from the bilateral relationship. [923] As a result Malaysia, while seeking a closer relationship with China, is bound to remain at the same time somewhat ambivalent. (The problem of an economically powerful indigenous Chinese minority is by no means confined to Malaysia: a Chinese minority, though relatively smaller than that in Malaysia, also plays the dominant role in the private sectors of Thailand, Indonesia, Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and the Philippines. [924])

[912] Clyde Prestowitz, Three Billion New Capitalists: The Great Shift of Wealth and Power to the East (New York: Basic Books, 2006), pp. 229-30.

[914] David Shambaugh, ‘ China Engages Asia: Reshaping the Regional Order’, International Security, 29: 3 (Winter 2004/5), p. 64.

[916] Ibid., pp. 99-100; ‘ China ’s “Soft Power” Is Winning Allies in Asia ’, International Herald Tribune, 12 July 2007.

[919] Quoted in Kang, China Rising, p. 127. This was a personal communication with the author.