The spread of English since 1945, driven by the global pre-eminence of the United States, has not affected the popularity of the main East Asian languages in their homelands. Not only has English failed to weaken or displace the main North-East Asian languages (Mandarin, Japanese and Korean), the languages themselves have also been relatively little touched by it. Japanese, it is true, has acquired many English loanwords, mainly nouns, but this reflects the typically Japanese way of adding foreign elements to their culture while leaving the Japanese core fundamentally untouched and unaffected. [339] It is fashionable in Japan — as elsewhere in the region — to wear T-shirts bearing an English phrase, or to have shops with English names, or to see advertising with English slogans, but this has no bearing on the extent to which the Japanese speak, or even desire to speak, English. Despite an enormous cohort of English teachers and many years of compulsory English at school, the vast majority of Japanese are unable to speak English with either enthusiasm or facility. [340] Like the English, they remain linguistically insular and unembarrassed by the fact. The Chinese, on the other hand, have become hugely enthusiastic learners of English during the last decade or so and many young educated Chinese speak the language with impressive fluency. One teacher has taken to conducting his classes in huge stadiums with over 20,000 all chanting English phrases in unison. But this Chinese enthusiasm for English in no way reflects a decline in the popularity of Chinese. On the contrary, English remains a strictly second language, acquired for the purpose of conversing with foreigners, an interlocutor language for the young, well-educated and ambitious urban elite. Chinese, unlike Japanese, possesses relatively few English loanwords — or indeed loanwords from any language — and relatively little external structural influence. It has been influenced by the rise of English, for example, in the greater use of polysyllabic words, but only in a limited way: [341] a proposal, several decades ago, to romanize Chinese by replacing characters with Pinyin transliteration came to nothing. [342]

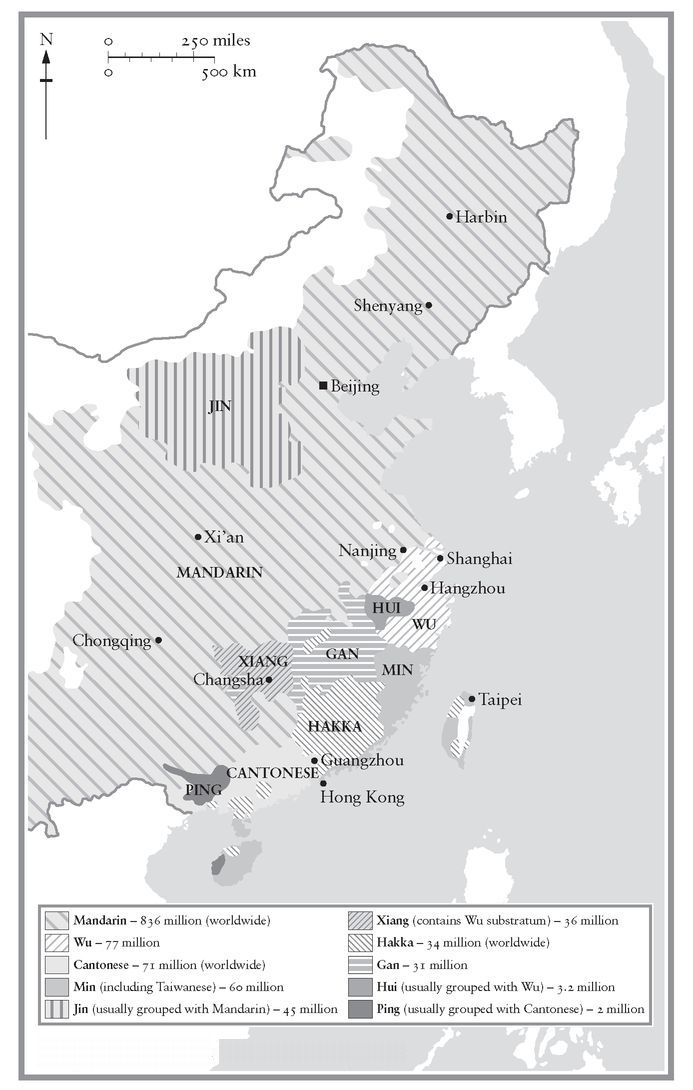

Map 8. The Main Chinese Languages

We should not be surprised by the continuing strength and resilience of Chinese. It is a language that dates back over three thousand years. Its pictographic writing system is shared by all the various Chinese — or Sinitic — languages, including Mandarin, Cantonese, Wu and Min: over 70 per cent of Chinese, well over 800 million people, speak just one of those languages, namely Mandarin, a figure which includes various dialects like Shanghainese, and the number is steadily rising as a result of the growing influence of television and the education system. [343] The fact that all Chinese languages and dialects share the same written script, even though they are often unintelligible to each other as spoken (being comparable in their diversity to the Romance languages), has been extremely important in maintaining a wider sense of Chinese identity. Chinese managed to survive long periods of foreign occupation by the Mongols and Manchus. Although both spoke different languages, they not only failed to impose them on the Chinese, but ended up being linguistically assimilated themselves. The influence of Chinese on the neighbouring but different languages of Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese has been immense. Each originally developed writing systems for their own languages by transforming or adding Chinese characters — known as hanja and kanji in the Korean and Japanese writing systems respectively. Even though these languages are quite different in linguistic structure from Chinese, such was the prestige of ancient Chinese scholarship that, over time, they became replete with Chinese vocabulary and have remained so ever since. Those who speak Chinese often refer to it as zhongguohuo, or ‘centre realm speech’: Sino-centrism, or what I will describe later as the Middle Kingdom mentality, even extends to how the Chinese perceive their language. Chinese has even managed to survive the onslaught of the alphabetic age, though in reality, of course, it would be well-nigh impossible to create an alphabetic language which could act as the writing system of so many different Chinese languages and a fifth of the world’s population. [344]

The only East Asian countries in which English has acquired a central role are Hong Kong and Singapore, where it is an official language; Malaysia, where it is very widely spoken although the official language is Bahasa Malaysia; and the Philippines, where English is still an official language alongside Tagalog. Apart from the Philippines, which was an American colony, these are all former British colonies. The popularity of English in Singapore and Malaysia owes much to the fact that English — as in India — has acted as a useful common language in a highly multiracial and multilingual environment. In the Philippines, English is used as a language of instruction in schools (from the age of twelve) in what is a complex linguistic archipelago, with Tagalog coexisting with many island dialects. The main language of Indonesia — a patchwork quilt of hundreds of languages — is Bahasa Indonesia, with the old colonial language, Dutch, now insignificant. Similarly, in Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, all former French colonies, French, once the official language in administration and education, has long since faded into relative obscurity.

This brings us to a further question. To what extent is English now permanently established as the global second language of choice? [345] It has been steadily strengthening its position in this respect more or less everywhere, often rapidly, with East Asia no exception. At an ASEAN (Association of South-East Asian Nations) meeting, or an international academic conference in Beijing, English is likely to be the main, or one of the main, languages of the proceedings. Throughout the region, there is a very strong desire to learn English. [346] There are several reasons why it is believed that the position English has acquired is unlikely to be reversed. Very considerable amounts of both social and personal capital have already been invested around the world in its acquisition and use, which constitute a powerful reason for its continuation and extension. English has established itself as the dominant language of a global media whose influence and penetration is likely to continue to grow. [347] The global ascendancy of the United States ensures that English will remain the foremost language in most fields, from international business and science to the internet and diplomacy. Finally, as the vehicle for the promotion and transmission of the values and norms of a culture, the Anglo-Saxon world has a major vested interest in ensuring the perpetuation of English as the lingua franca, which provides it with considerable economic, political and cultural benefits. [348]

Although English enjoys a formidable battery of assets, these do not render its position impregnable. The international penetration of a language is closely linked to the power and influence of its major patron. The United States may still be globally hegemonic, but, as we saw in Chapter 1, its relative global economic position is being eroded, and this is bound to impact on the fortunes of English in the longer term. English’s dominant position on the internet is already under serious challenge and will certainly not be sustained even in the relatively short run, with the number of Chinese users now exceeding those in the United States. [349] Although English remains the overwhelmingly dominant language of the global media, this situation is unlikely to continue indefinitely as new non-Western players enter the global media market and the main Western providers increasingly use local languages as a means of expanding their market. This process, in fact, is already well under way. Al-Jazeera, the independent Qatar-based Arab news channel, for example, broadcasts in multiple languages, as does the Indian-owned Zee TV, while Star TV in East Asia and Phoenix TV in China, both of which are owned by the Murdoch empire, broadcast in the local languages. [350] Finally, while English has enjoyed a privileged position with new technology — especially in computing — the growing diversification of technological innovation, together with the fact that computers are now able to support a large range of languages, means that English’s hitherto preponderant position in this field is by no means assured. [351]

[339] James Stanlaw, ‘English in Japanese Communicative Strategies’, in Braj B. Kachru, ed., The Other Tongue: English Across Cultures (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992), pp. 181-4. It has been estimated that 8 per cent of the total Japanese vocabulary is derived from English, with virtually no reverse traffic; ibid., p. 183. Also Braj B. Kachru, Asian Englishes: Beyond the Canon (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2005), p. 81.

[340] Kachru, Asian Englishes, pp. 191- 2. A survey in 1998 found that 81.7 per cent of Japanese only speak Japanese even though virtually no one else speaks their language; Dentsu Institute for Human Studies, Life in the Era of Globalisation: Uncertain Germans and Japanese Versus Confident Americans and British, the Second Comparative Analysis of Global Values (Tokyo: July 1998). Also, Kachru, Asian Englishes, Chapter 4.

[341] Chin-Chuan Cheng, ‘Chinese Varieties of English’, in Kachru, ed., The Other Tongue, p. 166.

[346] ‘Talk in English, Please, Korean Kids Told’, International Herald Tribune, 25-6 March 2006.

[347] Graddol, The Future of English, pp. 60–61; ‘Across All Cultures, English Says It All’, International Herald Tribune, 10 April 2007; ‘At Global Business Schools, English Adds Up’, International Herald Tribune, 11 April 2007.