I think one of the biggest differences between the Americans and the Chinese is that Americans are always trying to re-create themselves, always feel it is important to be the first person to do this or do that. Even America as a nation is always trying to re-create itself. The Chinese rarely even ask these questions, and as a nation seem to have more of a sense of where they come from. Of course, they are changing fast, but they don’t ask who they are, or constantly compare themselves with others. [334]

The irresistible conclusion is that the reason why the Chinese have a deep sense of their own identity is to be found in their long, continuous and rich history; in contrast, as products of a relatively new and young nation, Americans are in constant search of their identity.

The recognition that the Chinese exhibit certain cultural traits which can be explained by their history does not imply cultural essentialism, the idea that all nations and ethnic groups have a bundle of characteristics which remain fixed and unchanged over time. On the contrary, identities are constantly changing and being renegotiated. But that does not mean that cultural characteristics stemming from profound and very long-run influences — like climate, patterns of agriculture, language, the environment, family structure, cosmological beliefs or the longevity of history — don’t persist from the past and leave their mark on the present. According to Robert Boyd and Peter J. Richerson, who have extensively researched the relationship between cultural and genetic evolution, ‘an enormous amount of circumstantial evidence suggests that culturally transmitted traits are stable over time and in the face of changing environments.’ [335]

THE EXTENT OF WESTERNIZATION

Walk around Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, and virtually every street name is printed in English as well as Chinese. Switch on Taiwanese television and the most popular sports are basketball and baseball. Go to a movie on Saturday night and most of them, in a country internationally renowned for its film directors, are products of Hollywood. Go window-shopping in the underground mall below People’s Square in Shanghai, and many of the models used in the fashion photographs are Caucasian. Wander round the huge Ba Bai Ban department store in Pudong, and you’ll probably see many banners written in English. The top students at Shanghai ’s Fudan University want to do postgraduate studies at American universities or work for American multinationals in Shanghai. Middle-class Malaysians in their thirties are far more likely to have visited Europe or Australia than Japan and China. Go on a shopping spree in Tokyo ’s fashionable Harajuka or Shibuya districts and it won’t be long before you find yourself singing along to a Western pop song blaring out from a boutique or coffee shop.

I vividly recall a softly-spoken Malaysian lawyer telling me: ‘I am wearing your clothes, I speak your language, I watch your films, and today is whatever date it is because you say so.’ [336] Even the term ‘ Asia ’ was a European invention. Everywhere you go in the region, you feel the presence of the West. The sheer power and dynamism of Western modernity has set, and reset, the agenda for East Asia for almost two centuries. From colonialism to Hollywood, from the English language to basketball, from the solar calendar to Microsoft, from the Vietnam War to the IMF, the West has been, and is, present in the East in a way that the East has never been present in the West. Only in the form of Japan has Asian modernity, until the recent rise of China, exercised a significant impact on the West. Otherwise, the presence of the East in the West is largely confined to the mainly post-colonial migration of large numbers of Chinese, Indians, Koreans and others to North America and Europe and their consequent impact on the West in terms, first and foremost, of food, but also language, religion and culture. The constant imperative, both past and present, for Asian nations to negotiate with Western power, influence and presence — first in the era of colonialism (with every East Asian country colonized apart from Japan and Thailand) and then in the post-war era of American hegemony — constitutes a fundamental difference between East Asian and Western modernity.

This brings us to two critical questions. Firstly, to what extent have East Asian societies been influenced and shaped by Western modernity? Secondly, in the process of modernization are they becoming more Western, or less Western, or even, paradoxically, both at the same time? These questions do not lend themselves to simple answers. They vary from one society to another and from one sphere to another in any given society. History, as one would expect, affects the answers a great deal — in particular, whether or not a country was colonized, and if so when and for how long. At the one extreme lie the Philippines — first colonized by the Spanish in 1542, then by the United States in 1899, achieving independence only in 1946 — and Hong Kong, seized by the British after the First Opium War in 1842 and only returned to China in 1997; at the other lies Japan, which managed to escape colonization altogether.

In order to explore the extent of Western influence, and whether or not it is increasing, let us consider four very different examples — language, the body, food and politics.

Language

The language that a group shares is precisely the medium in which memories of their joint history can be shared. Languages make possible both the living of a common history and the telling of it… Every language is learnt by the young from the old, so that every living language is the embodiment of a tradition. [337]

Languages are not simply a means of communication, but embody and articulate a culture. To lose one’s language — and thousands of languages are likely to become extinct over the course of this century as they did in the last — is also to lose, in very large measure, one’s culture. As Hung Tze Jan, the successful Taiwanese publisher, puts it:

Language is essential to form an idea — as long as you keep your unique language, you keep your way of creating ideas, your way of thinking. The traditions are kept in the language. Language was an obstacle to us going out, but it also prevented others getting inside. Language was our Great Wall. [338]

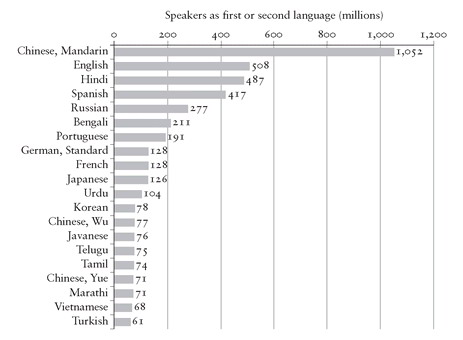

East Asia is home to almost half the top twenty most widely spoken languages in the world today. Unlike the European languages, which were essentially spread by overseas conquest (the reason why the number of English, Spanish or Portuguese speakers now greatly exceeds the population of the countries they originated from), East Asian languages have grown organically in their densely populated, rice-growing homelands, as a result of demographic trends and/or land-based territorial expansion. They are spoken overseas overwhelmingly as a result of migration and consequently only on a relatively small scale. Mandarin is the most widely spoken language in the world, far exceeding English, but the vast majority of Mandarin speakers live in China; English, by contrast, has flown the nest.

Figure 9. The world’s top twenty languages.

[334] BBC2, Proud to be Chinese (broadcast December 1998), transcript of interview with Katherine Gin.

[335] Boyd and Richerson, Culture and Evolutionary Process (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1985), p. 60.