b) In humans, all behavior (macro–and micro-) is a transform of internal neurological processes, and therefore carries information about those processes. All behavior, then, is in some way communication about the neurological organization of the individual — a person can't not communicate.

The goal of this process of information gathering is the goal of all of behavioral science, to decode the overt transforms of neurological strategies, which are generally not available to the consciousness of those in whom they operate, in order to gain understanding of how the representational components are organized with respect to one another.

The process of discovering regularities between an individual's observable behavior and their internal processes is an example of the process we have employed to generate all of our models of behavioristic. Gregory Bates on has elegantly formalized some of the properties of this process in his work:

"If from some perception X, it is possible to make better than random guesses about some Y, there is 'redundancy' between X and Y, 'X is a coded message about Y\ or 'Y is a transform of X', or 'X is a transform of Y' …" ("Reality and Redundancy" — 1975)

"… when an observer perceives only certain parts of a sequence or configuration of phenomena, he is in many cases able to guess, with better than random success, at the parts which he cannot immediately perceive (guessing that a tree will have roots, for example)." (Steps to an Ecology of Mind— 1973)

Note that this definition says nothing of statistical verification. Statistics may support or reveal patterns but they do not establish them; nor do they determine whether a pattern will be useful or not. Statistical averaging may sometimes be used to help find a pattern, but the statistics themselves are not the pattern, as they are often assumed to be. Indeed, the behavior we are studying becomes established, not on the basis of statistical averages, but on patterns. The child learning to speak does not assimilate the language by taking statistical averages of the meanings of words s/he is learning to use, but rather on the basis of the patterns offered by relatives, friends and others as the child grows up. The overwhelming majority of children become competent native speakers of the language they learn in this way.

The patterns and generalizations we offer concerning accessing cues can be and have been supported by experimental research, but we have chosen simply to present these generalizations and patterns as we have observed them in the more useful context of our professional experience. We will present no numbers, tables or graphs.

The ultimate success of a neurolinguistic programmer will depend on the ability to observe, identify and utilize the multitude of transforms and patterns that will be constantly offered to you in your ongoing sensory experience by the members of our species; not on the ability to measure and average types of behavior or to remember numbers and tables. We offer the generalizations in this book as a way to assist you to begin the process of expanding your own perceptual abilities, not as "laws". We suggest that you develop a strategy with which to observe these patterns in your ongoing interactions and verify them for yourself until you have incorporated the strategy so thoroughly that you can let it drop out of consciousness. In our experience, the patterns we offer have held for every individual we have observed and questioned.

3.231 Eye Movements as Accessing Cues.

We have noticed that the eye movements people make as they are thinking and processing information provide a remarkably accurate index for sensory specific neurological activity. We introduced these patterns in Patterns II:

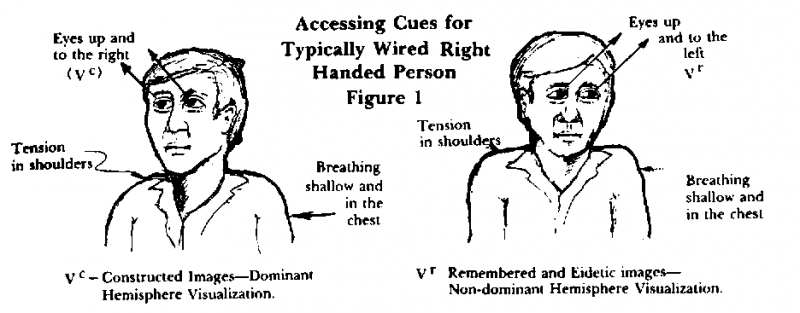

"When each of us selects the words we use to communicate to one another verbally, we typically select those words at the unconscious level of functioning. These words, then, indicate which portions of the world of internally and externally available experience we have access to at that moment in time. More specifically, the set of words known as predicates (verbs, adjectives and adverbs) are particularly indicative. Secondly, each of us has developed particular body movements which indicate to the astute observer which representational system we are using. Especially rich in significance are the eye scanning patterns which we have developed. Thus, for the student of hypnosis, predicates in the verbal system and eye scanning patterns in the non verbal system offer quick and powerful ways of determining which of the potential meaning making resources — the representational systems — the client is using at a moment in time, and therefore how to respond creatively to the client. Consider, for example, how many times you have asked someone a question and they have paused, said "Hmmmmm, let's see" and accompanying this verbalization they move their eyes up and to the left. Movement of the eyes up and to the left stimulates (in right handed people) eidetic images located in the non dominant hemisphere. The neurological pathways that come from the left side of both eyes (left visual fields) are represented in the right cerebral hemisphere (non dominant). The eye scanning movement up and to the left is a common way people use to stimulate that hemisphere as a method for accessing visual memory. Eye movements up and to the right conversely stimulate the left cerebral hemisphere and constructed images—that is, visual representations of things that the person has never seen before (see Patterns, volume I, page 182).

"Developing your skill in detecting the client's most highly valued representational system will give you access to an extremely powerful utilization tool for effective hypnotic communication. There are two principal ways which we have found effective in teaching people in our training seminars to refine their ability to detect representational systems:

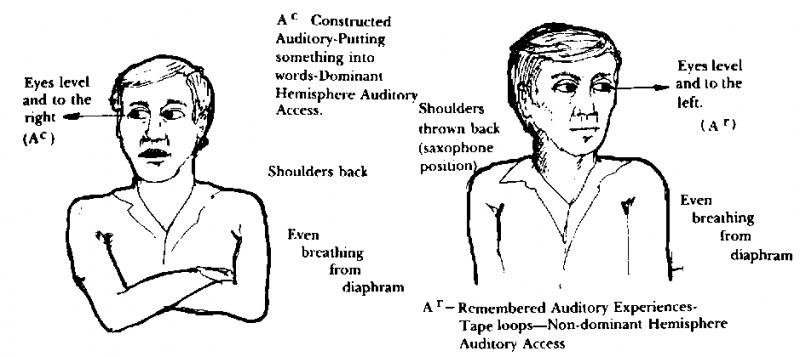

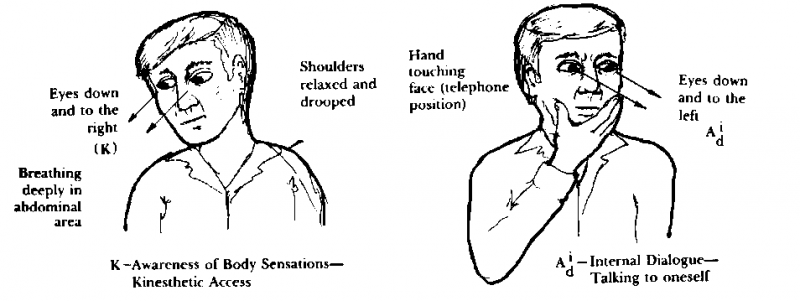

(1) attending to accessing cues which may be detected visually. Specifically (for the right–handed person):

accessing cue – representational system indicated

eyes up and to the left … - eidetic imagery (V)

eyes up and to the right … - constructed imagery (V)

eyes defocused in position … - imagery (V)

eyes down and to the left … - internal dialogue (A)

telephone positions … - internal dialogue (A)

eyes left or right, same level of gaze … - internal auditory (A)

eyes down and to the right … - body sensations (K)

hand[s] touching on midline … - body sensations (K)

(2) attending to the choice of predicates selected (typically, unconsciously) by the client to describe his experience (see Patterns, volume I, pages 68–76, 82–86 and The Structure of Magic, volume II, part I). When describing experiences, each of us selects words to describe the portions of experience we attend most closely to. Thus, as communicators, when we train ourselves to detect which representational system is presupposed by the words selected by our clients to describe their experience, we have information which we can utilize effectively in our communication with them.

"These are, of course, only two way of learning to detect representational systems — there are many others. We have found, for example, that breathing patterns are an excellent indicator of which representational system a person is using at a point in time to organize and represent their experience to themselves. During visualization, for example, the person's breathing tends to become shallow and high in the chest. Other equally useful indicators in our experience are the shifts in the tonal qualities of the person's voice, the tempo of speech, the color of the person's skin … We have presented two specific ways of detecting representational systems in sufficient detail to allow the reader to train him or herself to detect the representational system being used by a client at a point in time. Once you have comfortably mastered these two techniques — refined your ability to make these sensory distinctions — we suggest that you explore for yourselves other indicators which allow you to gain the same information. Such exercises in making sensory distinctions will not only increase your ability to be effective and graceful in your hypnotic communication but will increase and refine your ability to have the sensory experience which is, in our experience, the very foundation of effective communication and hypnosis."