As you listen to predicates, pay attention to those which may be unspecific with respect to representational systems. Words like "light" may be interpreted kinesthetically or visually. Adverbs like "clear" may also apply to more than one representational system —you may hear something clearly as well as see something clearly. Many words like this will be specified, of course, through context, or through accessing cues (which we will detail later).

Words like "understand," "identify," "sense," "know," "think," "become aware of," "notice," etc., are also unspecified with respect to representational systems. Each of these processes may occur through any of the representational systems. A good rule of thumb to employ when confronted with words that you are not sure of, a rule that applies to all elicitation procedures, is: when in doubt, ask. And keep asking (operating) until you get a description that is sensory specific.

For example, suppose you have asked somebody how they begin their creative strategy and they answer, "Well, I just start getting into it." This verbalization is not specific with respect to the representational system they are using, so you will want to ask, "How specifically do you 'get into it'?" In response to this question the person replies, "I start thinking about all of the things I could do with it." Again their response is unspecified with respect to their sensory process, so you ask, "How specifically do you start 'thinking' about all of the things you could do?" The person answers this question with, "I just look at it and start to see all of these ways of using it." With this answer the individual has identified the first two steps in the strategy: "looking at it" (visual, external — Ve) and "see all these ways of using it" (visual, internal — Vi). Note that the internal visual representations follow the external input, so that there will be no interference.

The individual might also answer the question with, "I get this feeling that I'm going to really do something good." Here the individual is specifying internal kinesthetic sensations, but does not tell you what they are triggered by. In this case, then, you would want to ask, "What happens right before you get those feelings?"

You might also get an answer like, "I start going, 'Yeh, this is going to be fun! I can do this and that …', and so on." Here, the person is actually quoting internal dialogue, specifying auditory, internal (Ai). Again, however, if you want to specify the external stimulus which cues this internal dialogue, you will want to ask, "And what happens just before you begin to say this to yourself?" The answer may range from "I put a record on that really gets me into a creative mood" (Ae) to "I go jogging" (Ke) to "I look at the clock and see that I have a lot of time." (Ve).

You may also consistently end up with an answer, of course, like "I don't know." This indicates that the step is out of consciousness for the individual. As they answer, however, you may notice that they look up and to the left. It is here that close attention to each individual's non–verbal accessing cues will be of extreme importance. These will be presented later in this section.

The best way we know to assist you in becoming proficient at accessing the kind of sensory specific information you will require for eliciting strategies is to practice the meta–model that we presented explicitly in The Structure of Magic I. The meta–model provides powerful verbal tools with which you can decode and break down practically any verbalization into the primary sensory experience from which it was derived. We strongly suggest you look over The Structure of Magic I if you wish to increase your verbal skills and intuitions for any purpose. This same tool has powerful applications in decision making and management situations for securing high quality information.

Also, listen for predicate combinations which indicate synesthesia patterns. If someone says, "That looks uncomfortable, " the term "uncomfortable" does not constitute a visual description. A visual description has to take place in terms of colors, shapes, depth, position and brightness. This utterance is rather a description of a visual–kinesthetic synesthesia — an interpretation resulting from the feelings the individual derives from looking at the phenomenon she is remarking about, probably based on past experience. Other examples of this kind of language would be:

"It sounds like a colorful place" (auditory–visual).

"Don't look at me with that tone of voice" (visual–auditory).

"It sounded frightening" (auditory–kinesthetic).

The Structure of Magic II contains many useful examples and exercises that will amplify your abilities to hear interpretive language and break it down into sensory specific descriptions.

3.22 Expanding 4–tuple Notation — Part 1.

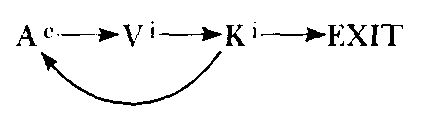

Thus far we have presented, through the 4–tuple, two major distinctions with which to classify and notate the steps in the strategy that you are extracting and unpacking:

1) Representational systems — auditory (A), visual (V), kinesthetic (K), and olfactory/gustatory (O)—and

2) Whether the representational system is oriented toward internally generated experience (indicated through a superscript "i") or toward experience which is coming from sources external to the individual (indicated by a superscript "e").

There are, of course, many possible distinctions that could be made about a particular step in a strategy as you analyze it in finer detail, such as color, location, pitch, clarity, etc., each of which may be useful at some time to achieve a specific outcome. As you choose the level of detail at which you will classify the representations in the strategy you are extracting, you'll want to opt for the description which is most elegant — that is, the one which employs the fewest distinctions but is still able to secure the outcome for which it was designed.

We have found the two distinctions presented so far to be the most essential for any adequate description of an experience. At times it may be important to add other modifiers into your notational description of a strategy, indicating which steps are involved in testing and operations, and checking the content experience being run through the strategy. We did this when we were identifying the difference between the constructed visual image (Vic) and the remembered visual image (Vir) in describing the test that took place in the visual spelling strategy. Memory (recall) and construction (imagination and fantasy) are formal distinctions that can be made for the internally generated experience in any of the representational systems, and seem to be a result of the functional differences ascribed to the two cerebral hemispheres in human beings.

Much research in recent years has been done on the functional differences in the neurological processing between the dominant hemisphere (the left cerebral hemisphere in most right–handed people) and the non–dominant hemisphere (the right cerebral hemisphere in right–handed people). The dominant hemisphere, it is claimed, tends to carry out linear, sequential, cause–effect type processing and, as a result, is responsible for the manipulation and construction of our internally generated experience. The non–dominant hemisphere, it is claimed, tends to carry out the more presentational, spatial, integrative, gestalten types of processing, and is thus responsible for much of the reaccessing and recalling of past sensory representations.[17]

17

It should be pointed out that hemispheric brain research to date has not incorporated the representational system model presented in this book. We suspect that many of the attributes ascribed to the different hemispheres may also be attributed to representational systems. Many of the conclusions of this research should be re–evaluated from the perspective of the NLP model.