Because of "handedness" (the fact that we tend to use one side of our body more than the other for many tasks), the dominant hemisphere will in many cases have a higher signal level than the activity taking place concurrently in the non–dominant hemisphere. As a result people are often more conscious of the activity taking place in their dominant hemisphere and less aware of non–dominant functions. We have found that making the distinction between dominant and non–dominant hemisphere functions (specifically those involving consciousness, memory and construction) is sometimes important for our work, particularly that involving altered states of consciousness (this is presented in detail in Patterns I & II). We will therefore often include some of these distinctions in our notation for strategies.

We have already used the "r" (remembered) and "c" (constructed) notation for these distinctions in this book. Using the "r" and "c" as a subscript to Vi, Ai, Ki or Oi, is redundant in the sense that we know that if someone is constructing or remembering an image they will be necessarily employing an internal orientation for that representational system. To make our notation more elegant, then, when it is necessary to indicate a remembered versus a constructed distinction, we will notate the "c" or "r" as a superscript in place of the "i". A constructed sound then will be noted as Ac; a remembered feeling will be noted as Kr ; and so forth.

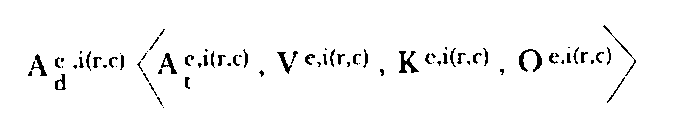

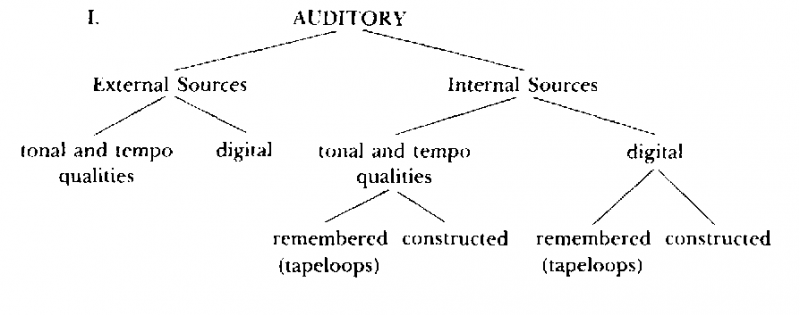

Another distinction related to hemispheric functioning that we consider useful is the difference between digital (verbal) representations in the auditory representational system, and those involving tonal and tempo (non–verbal) qualities. Our language (auditory, digital) representations tend to be primarily organized by neurological systems localized in our dominant hemisphere (the left hemisphere for right–handed people). Although remembered verbal experiences, such as tapeloops and cliches, become incorporated by the non–dominant hemisphere, this .hemisphere seems to be somewhat specialized for organizing the tonal, melodic and rhythmic portions of our auditory experience. The information carried by each of these different processes will often have a very different functional significance. The digital portions of our communications belong to a class of experience that we refer to as "secondary experience." Secondary experience is composed of the representations that we use to code our primary experience — secondary experience (such as words and symbols) are only meaningful in terms of the primary sensory representations that they anchor for us. This is why we will often show the digital[18] component of an experience to be outside of the 4–tuple:

Here we have distinguished between the tonal and digital portion of our auditory representational system by subscripting with a "d" for digital or verbal, and a "t" for tonal and tempo qualities. (See Patterns II pp. 17–19 for a more explicit discussion of this distinction).

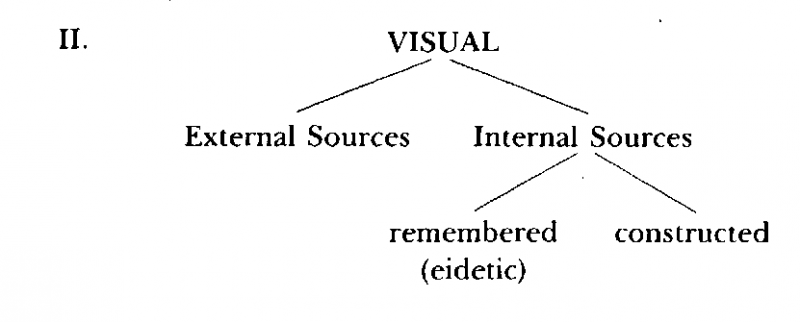

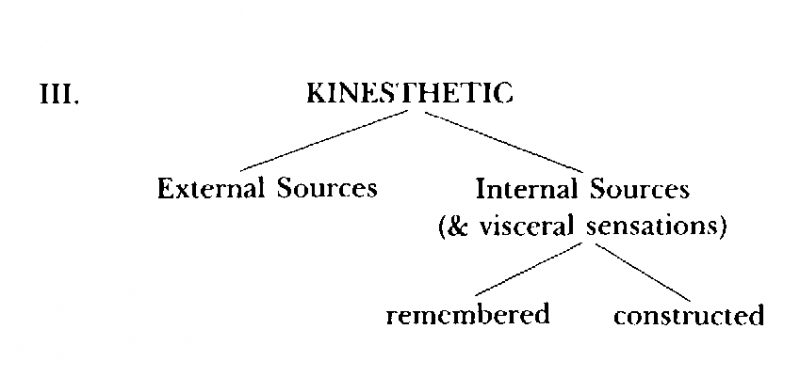

We have also indicated in this diagram the remembered and constructed distinctions as being possible subcategories of the internally generated experience.

Another possible distinction you may wish to make is that between the tactile (somatosensory) and visceral (emotional and proprioceptive) portions of kinesthetic experience.[19] Sometimes emotional or visceral representations will have a different functional significance for the behavioral task than those which involve purely external tactile sensations (pain, pressure and temperature). In general, however, we choose, for notational purposes, to class visceral sensations as kinesthetic internal experience (in the same category as remembered and constructed kinesthetic sensations).

As we said before, choose to make the distinctions you determine to be necessary to achieve the outcome you are working towards. It is sometimes important to break down the auditory digital aspects of someone's strategy into the corresponding meta–model category. For instance, we have observed that in many people the appearance of modal operators of necessity (words like "should," "must," "have to," "is necessary," "need to," etc.) in the verbal portions of their motivation or decision strategies often trigger the kinesthetic sensations of anxiety or stress. If they change these words to modal operators of possibility (words like "can," "is possible," "will," etc.) they are still able to achieve the outcome of the strategy but experience much less stress and discomfort.

You can also feel free to customize your notational system to fit your own needs, and to include distinctions that you think are important for the strategies that you find yourself working with. The distinctions we have offered here simply constitute what we believe to be the most minimal and elegant set of distinctions with which to analyze and notate strategy steps.[20]

3.23 Unpacking Strategies Through Accessing Cues.

We have previously mentioned that the verbal portion of our communication constitutes only one aspect of the entire process of communication. In fact, in our way of thinking, it often constitutes the least important part of the communication. A tremendous amount of information is communicated through the nonverbal (tonal, gestural and tactile) aspect of our communication, that typically takes place beneath the conscious awareness of most . people. Further, most people are unconscious of the vast majority of representations that pass through their neurological systems as they cycle through their strategies. It is very difficult for many people to tune into their actual sensory experience, or to communicate it verbally.

By paying close attention to accessing cues and the non–verbal portions of people's behavior, you can pick up a vast wealth of information that most often passes by people's conscious attention and defies their abilities to verbalize. The behavioral accessing cues that an individual employs to tune his or her neurology to single out one particular representational system through which to accept and process some input at a particular point in time, will provide you with an excellent index with which to identify the representational system being employed for a particular strategy step. These cues will directly indicate the representational system they are being used to access. This becomes very useful when the rapid and complex representational sequences that make up some strategies are not available through the verbal report of the individual who has displayed the strategy.

In this book we will be detailing only a few of an endless range of possible indicators and accessing mechanisms, all of which are available to your ongoing sensory experience. By paying attention to the systematic and recurrent behaviors that people go through as they communicate and act, we have discovered a number of non–verbal cues which may be used to index the sensory specific processes people run through during behavioral activity. These include eye position, tonal and tempo qualities of the voice, breathing rate and position, skin color changes, body temperature, heart rate, posture and muscle tonus, even EEG activity.[21] The two basic principles that underly our method of classification are:

a) Any occurrence in one part of a system (such as the neurological and biological system that makes up a human being) will necessarily affect all of the other parts of that system in some way. When the patterns of interaction between the parts of the system are identified, the effects of the different parts of the system on one another can be predicted and utilized.

18

Digital representations may occur in any of the three major representational systems. The written symbols you are reading now are examples of visual digital (Vd) representations. Braille constitutes kinesthetic digital (Kd ) representations.

19

Many of the visceral, emotional and proprioceptive body sensations are mediated primarily by lower and evolutionary older brain structures like the lymbic system, and have no projection to the cerebral cortex.

20

We can show the distinctions we have presented as a set of hierarchic tree structures, beginning at the top with the most basic classifications:

21

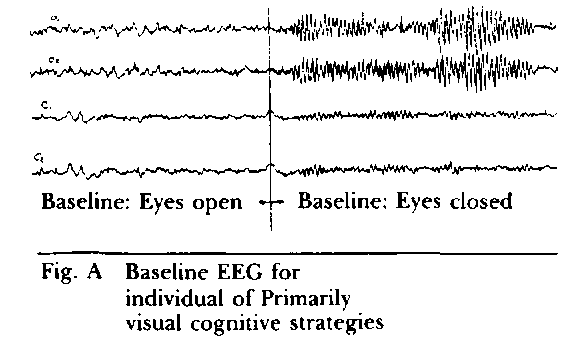

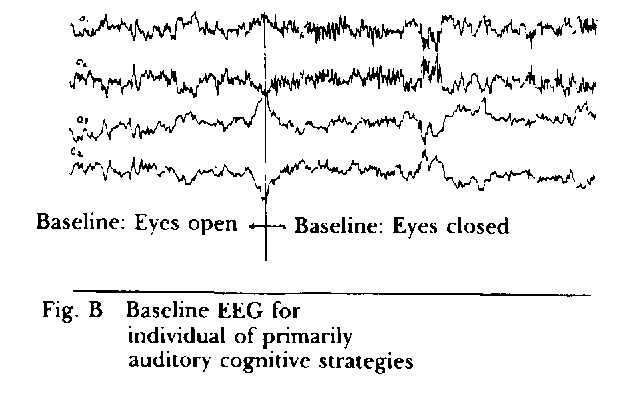

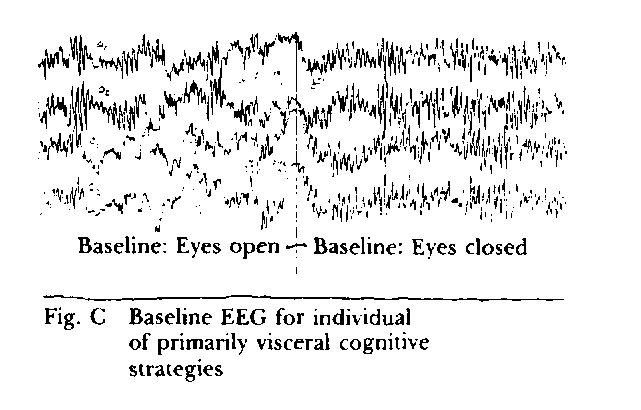

One of the authors of this book, Robert Dilts, has conducted research involving EEG and representational systems. Specifically, he examined the correlations between the primary, or most highly valued, representational system and the baseline EEG patterns of the individual, with their eyes alternately opened and closed. Although the research has primarily involved two pilot studies, and the methodology still needs improvement, it has shown a startling relationship between the most highly valued representational system and baseline EEG patterns.

Baseline EEG description: Low amplitude beta (over 16 Hz) activity when subject's eyes are open and subject is at rest. Spindles of alpha waves (8–12 Hz) appear when the subject closes his or her eyes.

Primary representational system: Visual.

Baseline EEG description: High amplitude beta activity with some intermitant alpha activity whether eyes are open or closed.

Primary representational system: Auditory.

Baseline EEG description: Low amplitude beta whether eyes are open or closed.

Primary representational system: Kinesthetic (tactile–motor)

Baseline EEG description: High amplitude alpha waves, whether the subject's eyes are open or closed.

Primary representational system: Kinesthetic (visceral)

The following are generalizations of these patterns for EEG surface electrodes placed over the occipital (visual) cortex of the subjects: