I don’t generally recommend pounding the plant because it breaks down the fiber, but if you simply must pound it, be sure to use a wide flat object such as a piece of log or a large wooden mallet. And, since the idea is to keep the fibers as long as possible, be careful not to break them in the process. Remember, cordage made with long pieces of fiber is stronger than that made with several short ones spliced together.

If you want fine, silky fiber threads, you can soak the leaves after they are scraped (or pounded gently with a mallet). Soaking causes the green matter to decay and separate from the fibers. This process is called retting. Early people understood the process of retting, and it is still done in industry today, using chemicals to speed the process.

How To Make Cordage

Cording is the process of preparing the fibers of various plants for weaving, basketry and other uses. It precedes and is believed to be the forerunner of basketmaking, although cording differs slightly from both basketmaking and weaving.

To make cordage from yucca fibers:

▲ Separate the fibers and lay them out uniformly. The yucca leaf is larger at the bottom than at the top, so the fibers are thicker at the base.

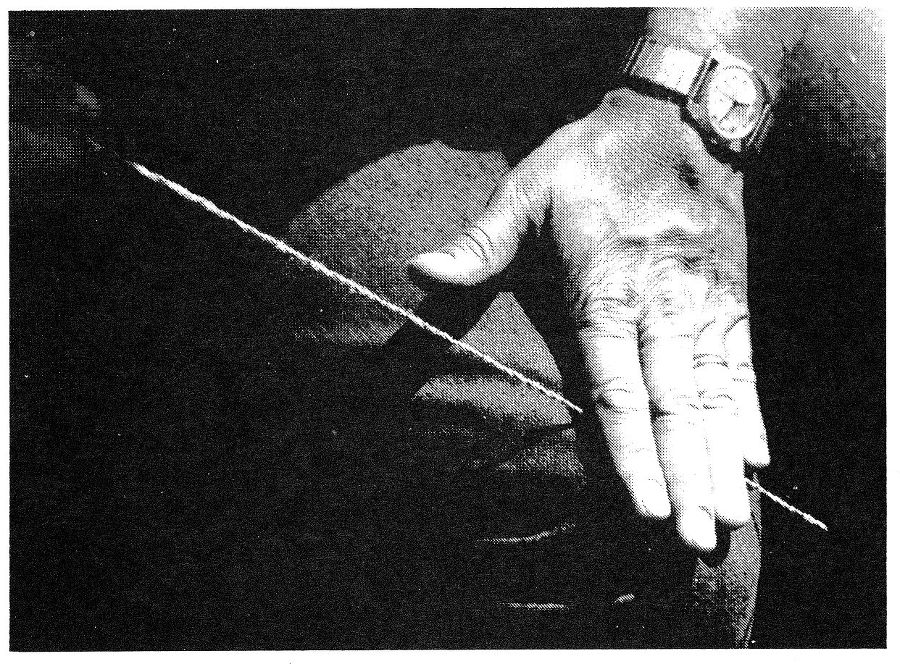

▲ Roll a long length of fiber down your leg with your open palm until it is round and reasonably uniform in size.

▲ Bend the resulting string about two-thirds in half—or leave one end about one-third longer than the other.

▲ The small loop in the bend is your starting point and should be held between the left thumb and forefinger (if you are right-handed).

Roll the long fibers with the palm of the hand on the thigh until the strand is uniform. (photo by Linda Jamison)

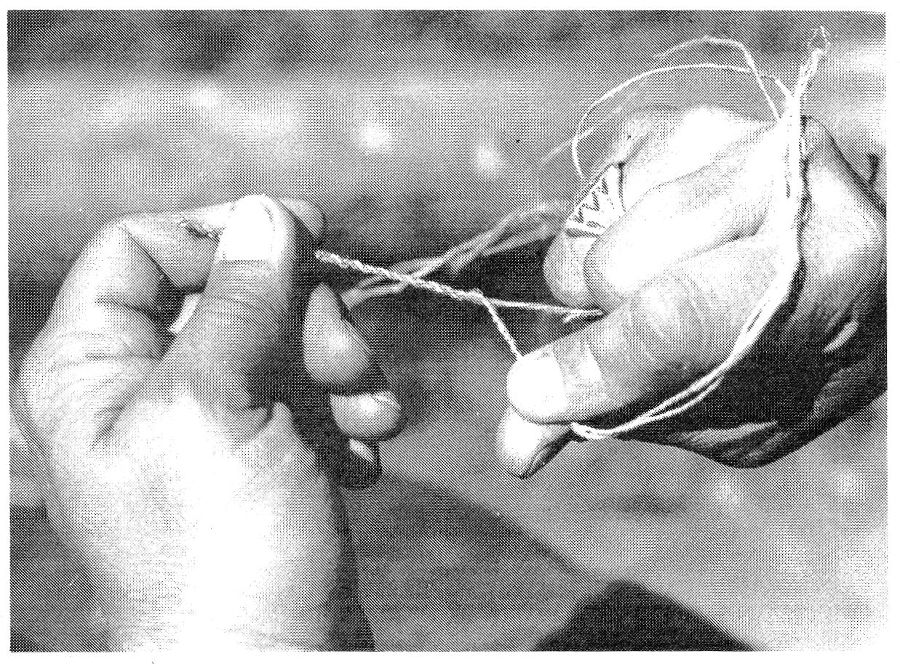

▲ You now have two loose ends hanging from the loop. Hold the twist secure, and twirl the top piece clockwise between the right thumb and forefingers.

Fold the twisted top strand counter-clockwise over the untwisted strand while holding the loop secure in the left hand. (Photo by Linda Jamison)

▲ Then fold the strand you have just twisted toward you, or counter-clockwise, and repeat the procedure with the opposite strand, moving the fingers on the left hand toward each new twist to hold it secure.

▲ When you reach about three inches from the end of your shortest strand, lay a new piece alongside the short end, overlapping it to give a strong splice, and roll the two together.

▲ Continue the twisting and folding until the desired length is reached.

Your cordage will not unravel because of the clock-wise, counterclockwise twist which actually tightens against itself.

The strength of the cord will depend on the thickness of the strand and the quality of your materials; two or three strands of cordage may be twisted together in the same manner for more strength.

Hint: Be sure that your splices are not at the same point, or opposite in your cordage, as this will weaken the strand. Making uniform strands will insure against weak spots.

To separate the pulp from the fiber, immerse the leaves totally in water for several days, agitating them occasionally, but be careful not to soak them too long or the fibers will be damaged in the process.

Cordage

Many of the early uses of cordage are known. Lacking the modern conveniences we have today—nuts, bolts, screws, nails, tape—primitive people tied their world together.

They tied their arrowheads to shafts, tied their game onto their waistbands for easy carrying, tied branches and logs together for shelter against the elements, tied babies in carriers and then to the mother. They also tied their clothing together, and made clotheslines for hanging up their belongings. They made breechclouts, ornamental hair bindings, various sorts of straps, braids for the foundation of fur and feather cord, thread for mending, and sometimes combined yucca cordage with other materials for greater strength.

As my children grew up, they were introduced to aboriginal skills early, and making yucca cordage provided a good learning experience. Once, while on a road trip, we stopped and gathered some yucca leaves and I taught them to make cordage, then we played a game to see who could make the longest piece first. It also taught a history lesson: the history of the early people of this and other lands.

Cording also has definite therapeutic value in stressful situations. It takes little or no concentration, yet is productive. Cording allows the mind to rest while productive, often the very process which helps an individual make correct decisions about future actions. And, there is satisfaction in seeing the complete metamorphosis as plant fibers become a useful item by your own hand.

The actual process of cording is far more difficult to explain than it is to do. By my own measure, a person becomes an expert corder upon completing 25 feet or more of cordage. Netting containing many miles of cordage has been found by archaeologists in cave dwellings.

Although yucca cordage is very strong, I don’t recommend it for bowstring, nor is rope generally made from yucca fiber, but several cords of yucca braided together will result in a very strong strand.

Fur cord and feather cord mixed with yucca fiber was made and used by prehistoric Southwestern people. To make fur cordage, rabbit skins or the skins of other small, fur-bearing animals are cut into narrow strips which are then joined; these are wrapped over or twined together with yucca cordage.

Feather cordage is made by stripping the feathers down the midrib, then twisting the half piece spirally with yucca cordage. In early times, turkey wing and tail feathers were used. Fur and feather cordage can then be woven into warm blankets for sleeping, robes, sandals and other items.

Basketry

In the days before pottery, early peoples were gleaners and named Basketmakers because of their expertise in this form of art, which requires an intimate knowledge of fiber as well as manual skill. Then, in addition to knowing what to use, one must know where and when and how to collect it. So discovery of the yucca, as well as the herbs to color the fibers, must have been a trial-and-error procedure, requiring countless years and endless effort.

There are hundreds of legends about basketry and its origin, but basketmaking probably began with the weaving of nets. In early days, gourds were used to carry water. They were clumsy to handle, difficult to transport and fragile. Eventually water receptacles were baskets, waterproofed on the inside with pitch (pinon gum).

Obviously, the materials used for the basketry by any culture is largely determined by the environment, and in the Southwest yucca was plentiful and widely used in basketry for gathering, for cooking utensils, for sieves, and bowls, as well as for ceremonial and other uses.

In primitive times, coiled baskets were made using a thick bundle of yucca leaves as a filler with the outer wrapping made from long splits of fiber from the same plant. Sometimes the yucca fiber was first twined into cordage, then woven into a functional form.

Yucca leaves can be cut any time for basketry. If you want a yellow-green color use the mature leaves; if you want a bright green basket, use fresh, young leaves. The heart leaves provide white fibers.

Weaving

Since sheep were not introduced to the New World until after 1540, and cotton was not believed to have been cultivated in the Southwest until about 500-700 A.D. (later for some locations where there was not enough water for cultivation), yucca was the primary material used by early people of the Southwest in textile weaving because of its wide distribution and great abundance.