In the fall of 1554, a very young Catawba boy stood wide-eyed in the cool shade of the big trees on the edge of an open field and watched a hunter shoot a thistle-fletched dart from a rivercane blowgun.

It sped from the muzzle in a blur, and before the boy could blink or think or try to understand, it was there-stuck firmly in the chest of a rabbit now lying still in a patch of blue-stemmed grass.

To the hunter, this boy was not just any boy. This was his son. The only son who would carry on the practice of making and using this blowgun. The only one who would be entrusted to pass on this craft and teach his son who would follow.

To the boy, this man was a magician. With a few sticks and a tuft of dried plant fibers he had opened a door as only a father can do. A father, a son and a rivercane blowgun-tied up tightly forever in a bundle of survival and living tradition.

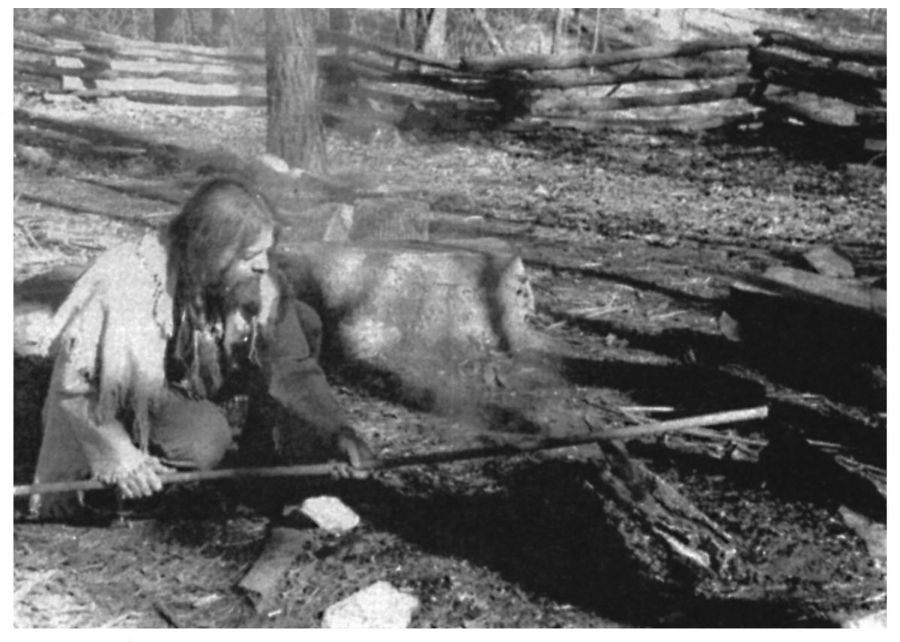

The author heat straightening the blowgun blank. Bends both at and between the joints must be straightened before interior work begins. (Photo: Michael Eldredge)

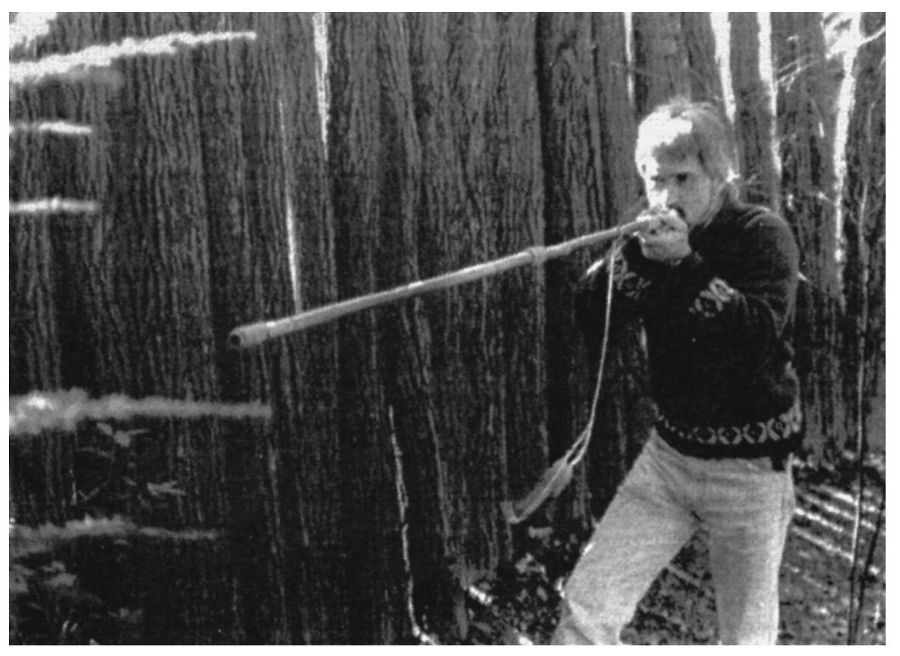

Proper shooting technique: both hands are held at the mouthpiece end in such a way as to make an airtight seal. The exhale which sends the dart on its way is short and forceful. (Photo: Steve Watts)

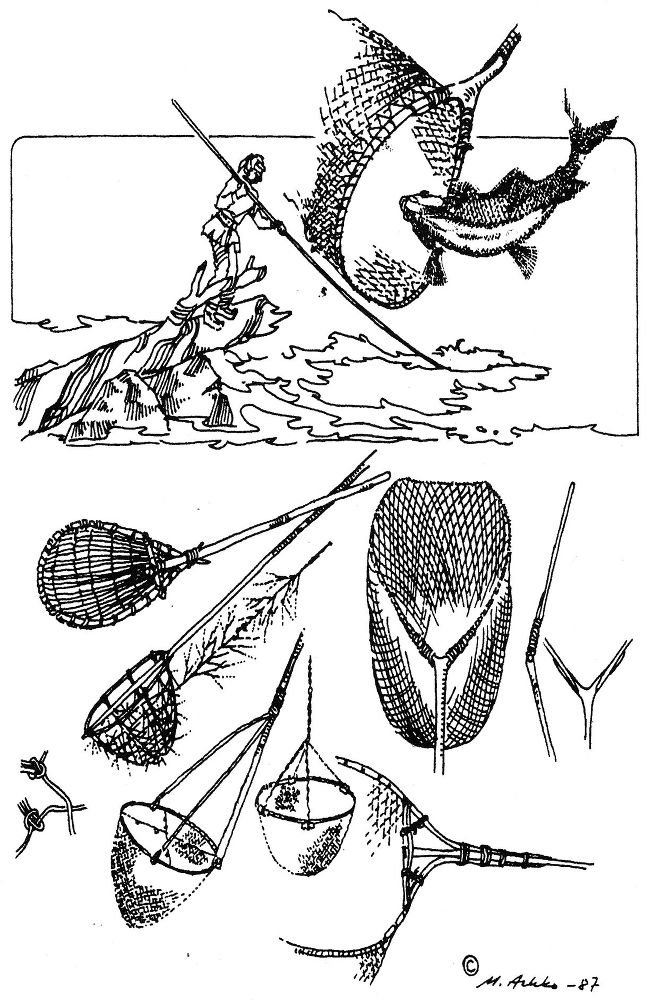

Ancient fishermen used landing nets to get salmon and whitefish during the spawning season. Many Lapps, Finns and other Arctic folk still use this method.

Turkka Aaltonen

Old Finnish Hunting and Fishing Techniques

It is important for every survivalist in the Arctic to learn It is important for every survivalist in the Arctic to learn to snare ptarmigan, that’s why we teach it every winter in the Finnish Army and Air Force survival training. If you can snare ptarmigans, you can use the same method for grouse and other woodland birds.

The ancestors of the Lapps who came to Finland and Scandinavia following the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago, were reindeer and seal hunters and fishermen. At this time nature was rich with game and fish.

Finland was first inhabited about 9,500 B.C., the people of that time followed the enormous droves of wild reindeer when they came north. Signs of their presence are still evident near the Central Volga and Ural Mountains. The Finns were really the last of the primitive cultures.

The closest ancestry to today’s Finns are Carelians, Estonians and distant relations among Hungarians. In Russia and Siberia there are still many small groups of Finns living under Russian rule.

The climate and flora are very similar in Scandinavia and Western Siberia and there are similarities in North America as well. For this reason the way of life, occupations, and some folklore is often similar.

The basic weapons for ancient Finns were the hunting spear, bow and arrows, axe and knife. Because they had the bow, there is no proof that early Finns used the atlatl. At that time they also used spears, harpoons and leisters (multi-forked spears). Our hunting spear was a pointed weapon, not meant for throwing. The oldest spearheads were made of bone tubes like those of the shin bone of elk or wild reindeer. If the hunter put some sharp points on both sides of this bone spearhead, it became a very effective weapon for big game or the large brown bear. Used without the shaft, the spearhead became a dagger or knife.

Finnish hunters traveled by skis, carrying a hunting spear which served twofold as a ski pole. Old skis were unpaired. the left ski was long and heavy while the right ski was short and light for kicking speed. Very often some fur was attached under the right ski for friction.

Hunting spears were used in Finland from the Stone Age to the 1800s. Some old bear hunters tried flintlock rifles, but the climate often caused their gunpowder to be damp. Bears don’t wait for you to dry out gunpowder, and the hunters learned that it is better to use cold steel—sturdy hunting spears. We still have many brown bears in Finland. In the old days it was considered a sacred animal—son of the forest gods.

The oldest hunting bows were longbows made of a single staff of juniper or yew. After the stick longbow period, Finns began to build bows with a combination of woods. These bows were about 160-170 centimeters long. No one know for sure how strong they were, although they probably gauged forty to seventy pounds of pull. The archer pulled the bow in the mongolian style, like Ishi.a

The basic construction was like that of all oriental bows. The Finns used two or three different tree species and glue made from perch skin. The finished bow was coated with a tight tape made from birch bark. The belly of the bow was made of pine or spruce and the backside was always made of birch. Sometimes the tips were made from the limbs of the bird cherry tree (Prunus padus). All parts were glued with fish skin glue. The string was made from sinew, or in later times, from nettle fibers.

The material for the arrow shaft was the straight wood of the pine tree. Arrows for the longbow were made by whittling, but crossbow arrows were made on a primitive lathe. Hawk and sea eagle feathers were used for fletching.

All bowhunters, including Finns, had special arrows for different animals: birds, fish and also a whistling arrow to frighten flying mallards back to the water. Wild ducks think that the whistling arrow is a diving eagle or goshawk. It is much easier to shoot mallards with a bow and arrow when they are on the surface of the water.

The crossbow displaced the longbow around 1500. Nobility and the military already had firearms by this time, but they were forbidden to ordinary folks. At this time Finns suffered under heavy Swedish exploitation, and only the wilderness and its freedom gave them the ability to survive. In the far north they still use the crossbow and special blunt-tipped arrows for squirrel hunting. These blunt-tipped arrows are made on primitive hand-lathes.

Wild reindeer were hunted in many ways; pitfalls and traps were used most often. Hunters knew that the annual migratory route of the reindeer was always the same so Finns built long fences with gates, and in every gate was a pitfall or trap. The long fence was located in a narrow area between two lakes. Like native North Americans, ancient Finnish hunters used the entire reindeer—nothing was wasted.

About one thousand years ago Finnish fur traders were very rich and had great influence. The red fox was very popular at that time, and the fur hunters killed them in all possible ways. One popular method which seems crude and even cruel by today’s standards, was the use of pawboardsmade from a tree trunk with an axe. In the middle of the pawboard was a spike for bait, such as a hare’s head. On both sides of the spike were long narrow slits. When the fox leapt up for the bait, it’s front leg became wedged in the slit. The whole trap is about 180 centimeters high.

During the fur trade era, squirrel fur was very popular in Europe. In fact, squirrel was so important to fur traders that the name for squirrel fur is “raha”, which means money in today’s Finnish language.

Squirrels were hunted with traps and snares, but those methods are almost all forbidden for hunting in Europe today, with the exception of Ptarmigan, which you can legally hunt with snares in the winter. But, you must be a native inhabitant of one of the three northern territories of Finland to do so. Catching ptarmigan with snares is one of the last connections to the old hunting traditions.