Always cut and store an ample supply of firewood in your woodshed in a standing camp. You never know when you may get a spell of rainy weather. Lighting a fire with wood soaked after a heavy night’s rain is not easy, even for the expert, and you’ll appreciate your store of dry wood.

After rain or heavy dew, you can start a fire by picking a big handful of thin dead twigs from nearby bushes. Hold these in your hand and apply the match flame to the end of the twigs. Keep twisting and turning until the whole handful is well alight.

If the twigs are too wet you may have to make a few “fuzz” sticks. Select dead wood standing from a shrub and break into sticks about f-inch thick and ten inches long. Cut away the wet outer wood, and trim the dry wood down in feathers. Three or four of these “fuzz” sticks will start your fire.

If it is raining heavily at the time, start your fire in your tent, and carry the twigs or “fuzz” sticks when well alight to the fireplace in your billy. Shield the early fire from the rain with your body. A slush lamp (page 101) will always start a fire, even with wet twigs.

The bandage in your first-aid kit previously soaked in kerosene will give you a starter for a fire. The kerosene will not affect the usefulness of the bandage.

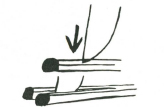

You can make one match light two fires by splitting the match. Hold the point of a sharp knife just below the head of the match and press down sharply. When using a split match to light a fire prime the twigs with dry grass or teased dry bark fibre.

BOILING AND BAKING WITHOUT UTENSILS

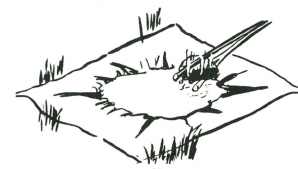

In emergency you may want to boil water, or cook food in boiling water, and you have no billy or utensil of any kind. This difficulty can be overcome by scooping a shallow hole in the ground and lining it with your groundsheet, some newspaper, a shirt, or any material which will hold the water. Build a quick fire of small sticks in which to heat twenty or thirty stones each two or three inches in diameter. Be very careful not to take these stones from a creek bed. Such stones may explode in the fire and injure you.

Fill the shallow hole with water, and when the stones are nearly red hot, which will take at least ten minutes, lift them one at a time from the fire with a pair of fire tongs and put gently into the water in the hole. The hot stones will not burn the paper or cloth, and five or six stones will bring a couple of quarts of water to boiling point in a matter of two or three minutes. Boiling temperature can be maintained for an indefinite period by putting in the other stones singly. Remove the cold stones when you put the hot ones in.

BARK DISH OR COOLAMIN

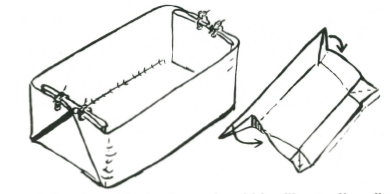

One method of improvising a cooking utensil is to make a bark dish, or Aboriginal “Coolamin”.

A flat piece of bark, of a species which will not split easily (the bark of many trees has this quality; one is the ficus family, or “fig trees”; test first by stripping a small piece of bark from one of the branches), is softened in the hands, and then the two ends are folded as in the illustration and pinned with a thin, sharpened peg or tied to hold them in position.

A coolamin can be used for all sorts of cooking with hot stones.

It is necessary to use the bark of green trees for a coolamin. If the sap is coloured, particularly if it is white or whitish and you can’t be sure it is “latex” or “rubber”, be extremely careful not to get it in your eyes. Many saps can “burn” your skin, or blind you temporarily.

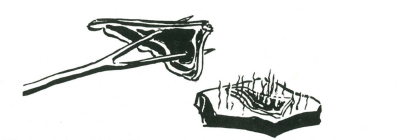

Meat can be grilled by using a forked stick with the fork ends sharpened. Alternatively, you can place a flat stone in the fire and get it nearly red hot. This hot flat stone should be removed from the fire and dusted clean. Place the meat to be cooked on it, and the meat will grill perfectly.

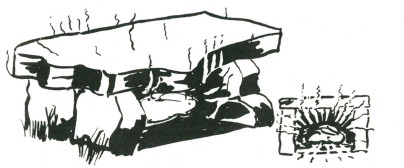

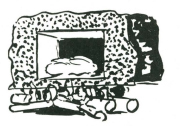

Baking can be done by making a stone oven, in which you light the fire and, when the stones are "sizzling" hot, draw the fire out of the oven, and place your scone or meat in the heated cavity. It will cook perfectly, and cannot burn, because the temperature is falling all the time.

An oil drum or large tin, if available, can be made into a good oven. Coat it thickly with several inches of clay. Build your fire either in the drum or tin, which is used like the stone oven, or alternatively, set the tin over a trench fireplace, and build one fire in the trench and another on top of the tin.

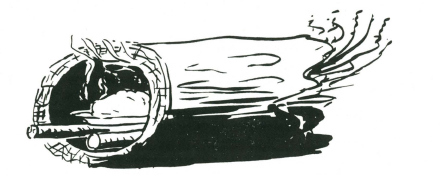

Another ready-made oven is to fire a hollow log or old stump. When the hollow is alight, place your cooking (covered on top and underneath) inside. You will have to watch all the time your food is cooking, because the fire may be too fierce and burn the baking. If the fire gets too fierce, damp it off with splashes of water.

The best baking is done by wrapping the food in either a coating of clay or damp paper, and then burying it in the hot dust beneath your camp fire. Food can be left for six to eight hours without spoiling if the fire in not built up. The food will not overcook and you can rely on it being tender. This is one of the best ways to cook freshly-killed meat, which would otherwise be tough. When cooking fish and game by this method, it is not necessary to pluck, skin or “draw” the carcase. The intestines will shrivel up, and the outer skin, whether fur or feathers, will peel off when you unwrap the clay or paper.

A variation of this method of “primitive” cooking is to dig a hole which is lined with stones. This hole is “fired” with a quick fire so that the stones are thoroughly heated. When the fire has died down and there is only hot white ash left, the food, wrapped as before, is placed on the heated stones, and the whole covered over with the dirt removed in the digging of the hole. In this, as in the previous method of cooking, the food will not spoil or be burnt, and can be left for six to eight hours.

The cooking methods outlined are adaptable to the needs of the moment. For instance, it would be waste of time to build a stone fireplace on which to cook a single meal when on a walking tour. It would be far easier to select a suitably sheltered position in the lee of an earthy bank or rock. On the other hand, in a standing camp, time is well spent in making a good fireplace, secure against wind and bad weather. It is assumed that the reader has sufficient common sense to use the cooking method and fireplace best suited to his needs and to clear trash away from the neighbourhood of the fire, also never to leave a fire burning in a vacant camp.

An egg can be baked by placing it in the hot ashes of your fire. But first you must pierce the shell and inside skin to allow the steam to escape. The egg will blow up if this is not done.