Individuals (other than when striking from a hidden ambush position) generally do not initiate a violent act without first exhibiting certain pre-assaultive behaviors (or “clues,” as they say in law enforcement settings). Perhaps the most prevalent pre-assaultive behavior threat indicator is verbal noncompliance. If a uniformed, armed police officer (or soldier) is pointing a weapon and yelling “Freeze” or “Halt,” compliance is required. Most reasonable people, regardless of whether the verbal warning is in a foreign language, will find it prudent to follow such direction. An individual should not be surprised if he is shot after openly disobeying a cop or soldier who is pointing a weapon and ordering him to freeze or halt.

Under certain circumstances, such as when a suspect ignores a command to “Drop the knife” or “Keep your hands where I can see them,” the verbal noncompliance might be an immediate precursor to deadly force. Under those circumstances, at the very minimum, the verbal noncompliance of a subject should place the officer or soldier in a heightened state of alertness and awareness that something may be awry. This is especially important at entry control points (ECPs) and traffic control points (TCPs), where the screening of many innocent persons and noncombatants might be interspersed with the quick, violent assault of an adversary.

More than any other part of the human body, the hands of a suspect are constantly a concern for most prudent law enforcement officers. The hands will most likely access the weapon or initiate the assault upon the suspect’s intended victim. That is why verbal noncompliance by a potentially armed suspect to a command “Show me your hands” must be viewed as a sign of demonstrated hostile intent or imminent hostile act. Under such circumstances, persons on patrol or guard duty would be foolhardy to wait to see a weapon before taking immediate action. The same holds true in combat settings, yet very few soldiers are ever taught this lifesaving fact. Many judge advocates and commanders wrongly instruct their warriors to wait until a threat actually points or fires his weapon before deadly force is authorized. Never accept such nonsense if written into a tactical directive or ROE: Take the time to educate your judge advocates or superiors on the tactical realities of such situations. They are oftentimes acting out of simple ignorance or “cutting and pasting” old ROE card information that is wrong.

More than one suspect or assailant dramatically increases the danger to a soldier or law enforcement officer. Despite Hollywood movies showing cops (or martial arts experts) fending off two, three, or more attackers, the advantage a group has over an individual is high and the odds are not in favor of the individual, no matter how skilled a fighter he may be. This is true even though the officer or soldier may possess the only firearm on the scene. In addition to the sheer physical advantage multiple assailants possess over the individual, multiple assailants are also a danger because of a tunnel vision dynamic that comes into play. In other words, a soldier may be so distracted by an “obvious” bad guy (either an actual or feigned threat), that he will exclude or not focus on other possible threats within the group until it is too late.

Again, soldiers are often faced with this dilemma at TCPs and ECPs. That is why it is critical that there be sufficient personnel present, hopefully in an overwatch position with a clear field of fire, to attenuate this problem. But when out on patrol or conducting peace-enforcing missions, soldiers may not have that luxury. They need to be trained on threat identification and recognize that a hostile crowd—even if apparently unarmed—can still present a very serious threat. If the mission allows, it may be prudent for the patrol to quickly exfiltrate an area to avoid a potentially ugly and uneven situation. But the soldiers have to first be trained on recognizing the problem before seeking solutions.

Previously used tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) of the enemy can be a huge building block in the development of assessing hostile intent. If the enemy has been known to use an injured civilian as a ruse to stop a convoy or divert the attention of a patrol, should that situation arise again, the patrol would be wise to go into “condition yellow” quickly; in other words be switched on and wary of attack.

Lastly, so long as it is efficiently and accurately pumped down to the lowest tactical levels, theater-specific intelligence can also be used as a building block to divine intent. The law does not require the soldier to be positive, only reasonable. Accordingly, tactical leaders have an ethical and moral responsibility to train those in their charge on both threat identification and proficient weapons handling. Those properly trained will be more likely to engage the enemy and less likely to kill noncombatants or friendly forces.

Appendix B

Armored Vehicle Recognition

In the recent past, armored vehicle identification was usually just a matter of distinguishing between vehicles manufactured by Warsaw Pact nations and those manufactured by NATO nations. However, even in those days it was sometimes difficult to tell the difference between vehicles on a simple friend-or-foe basis. In 2003 and 2004, several former Warsaw Pact nations joined NATO, bringing former Warsaw Pact equipment with them. In addition, changes in international relations have made it more likely that we will meet a third world nation’s troops, as experienced in our operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Most third world nations do not manufacture their own combat vehicles, but instead buy them from other countries. As a result, many of them have vehicles from nearly every manufacturing nation in the world.

As a result, one of the best ways to identify armored vehicles is to compare the observed vehicle characteristics with four known vehicle attributes or characteristics. Most, but not all armored vehicles have all four characteristic areas:

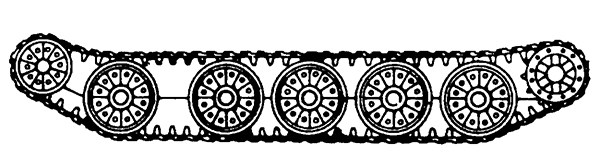

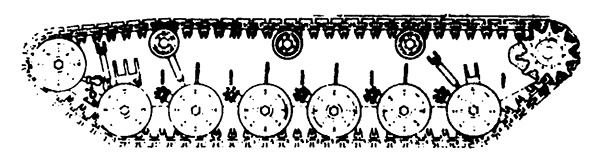

1.Track and suspension system. Many tanks can be recognized by their track and suspension systems unless grass, dirt, terrain, dust, or other factors are obscuring the tracks. To identify the track and suspension system, check to see whether it has support or return rollers.

•Most former Warsaw Pact vehicles have a flat (Christie) suspension system, without support or return rollers, without torsion bars, and unevenly spaced road wheels.

•Most NATO vehicles have a suspended track, support or return rollers, torsion bars, shock absorbers, and evenly spaced road wheels.

2.Turret. Most turrets can be grouped into three categories:

•Big, bulky turrets—older models.

•Well-sloped turrets—newer models.

•Streamlined turrets—newer models.

3.Main gun. Armament varies from machine guns to large cannons. In turreted vehicles, normally the heaviest armament is in the turret. Look for the main gun, the main gun bore evacuator, and its relative location on the main gun.

Types of main guns include:

•Smooth main gun, without bore evacuator or blast deflector.

•Main gun with bore evacuator.

•Main gun with bore evacuator and muzzle brake or blast deflector.

Types of muzzles include:

•Single-baffle.

•Double-baffle.

•Multibaffled.

4.Cupolas. The cupola is a small, turretlike projection normally on top of the turret. It is used by the vehicle commander and usually mounts a machine gun.

Studying these various characteristics will assist you in remembering unique attributes about various armored vehicles and ultimately allow you to identify most vehicles by nomenclature. The following pages contain common NATO and former Warsaw Pact armored vehicles.