ROE and EOF cards should not be used as a substitute for quality tactical training that incorporates situational training exercises and stress inducers. Additionally, the linear flowchart guidance provided by such cards may look good at a commander’s PowerPoint morning briefing, but they provide horrific legal and tactical guidance for a soldier at the tip of the spear.

The practical problem with such linear-based thinking is that at the tactical level it fails to account for simple physics. If a vehicle is approaching a checkpoint at a mere 30 miles per hour, that speed translates into 44 feet per second. So, if a soldier perceives that a vehicle a block away is a potential threat, he will only have a few seconds to observe, discern, decide what action to take, and then act. Additionally, it is impossible to provide a “checklist” that tells a warrior when he can and cannot shoot. The tactical situations whereby force in self-defense is authorized constantly change. This is why situational training exercises (STXs) are so critically important.

Effective STXs should provide an overview of the law and the tactical dynamics of deadly force encounters: action versus reaction, emotional intensity (the psycho-physiological reactions of humans under high-stress tactical environments), and wound ballistics. Combat should not be the first time that warriors viscerally experience these phenomena. It is important, therefore, to use non-lethal training aids like Simunitions or Ultimate Training Munitions in situational training exercises. It is also important to drill with judgment-based targets on live-fire ranges.

Such force-on-force training creates a level of “stress inoculation” against some of the more deadly aspects of fear and stress-induced physiological and psychological effects. Students should be forced to rely upon near-instantaneous judgment, which can only be honed by exposure to a variety of complex situations requiring immediate detection, decision, and reaction. Increased understanding of tactical threats cultivates judgment through the fluid integration of decision-making and tactical concerns. Very simply, confidence in Use of Force authority and skill leads to operator competence and increases the likelihood of killing more bad guys and potentially fewer civilians.

Soldiers are not born with an ability to discern between friend and foe. Many lessons learned from law enforcement concerning threat identification must be incorporated into the military’s training regimen. The first lesson is a psychological one: Human beings rarely, if ever, expect something bad to happen to them. It is always the other guy who gets into a car accident, the other family’s home that is burglarized, and always the other convoys that get hit by the IED. If you were expecting to get into a gunfight, wouldn’t you bring something bigger than a pistol or rifle? It is almost a universal reaction of surprise that greets most warriors and cops when they become involved in a deadly force encounter, even when responding to armed holdup calls and calls where, intellectually, the officers should have known a violent encounter was likely.

Also, Hollywood and television give a false impression on how bullets work. In the movies, a bad guy is blown through a window when struck by one round. Reality is something quite different. Consider the following account of a civil affairs soldier who was an Arkansas cop in his civilian life. He relates his ordeal of confronting two violent, armed robbers at a convenience store.

Rolling into the store parking lot, he saw two armed men running out the front door. His first reaction was one of surprise. As he got out of his car, he was surprised a second time: The two men did not flee. Instead, they charged at him with their weapons blazing. The officer’s first reaction was one of incredulity: Bad guys were supposed to run when confronted by the police. He quickly recovered his wits, retreated to the back of his vehicle, and then went into his training mode: front site on target/trigger press. He quickly and successfully hit both subjects multiple times. Again, to his surprise, only one subject went down immediately, while the second subject hurdled over his downed partner and continued to charge. The officer quickly performed a combat reload (without hesitation and without thinking) and put more rounds into the second bad guy, hitting him with a fatal T shot to the brain. [The fatal T describes that area of the face between the two eyes and the tip of the nose. If you mark this area on a two dimensional target, it creates a “T” shape: hence, the “fatal T.”] That subject was DRT (dead right there), with his automatic pistol empty and slide locked to the rear. The officer then shifted his attention back to the first, downed subject, who—unbelievably to the officer, having hit him with multiple rounds—was trying to push himself up off the ground to continue the attack. It took more rounds from the officer to finally finish the job of addressing that threat. This event profoundly shook the officer, but he reports that it was the fact that he was twice-surprised during the event that impacted him most.

This same type of surprise occurs in urban combat settings with surprising frequency, so training soldiers on this type of law enforcement example can only help soldiers learn what to expect and how to react. The first time they see a subject survive multiple hits should not be in a life-and-death combat setting. If they are stuck on a “qualification” mentality, they will never survive combat.

In addition, we are not born preprogrammed with much in the way of threat recognition. For instance, most reasonable adults, without training, would not recognize that an opponent who was “blading” his body into a pre-assaultive stance or balling his fists was showing signals of imminent attack. Neither prudence nor the law requires the law enforcement officer take the first punch in such a situation. In other words, the law does not require an officer to gamble with his life, nor is the Constitution a suicide pact. Similarly, members of the Armed Forces do not give up their inherent, God-given right to self-defense. In fact, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Standing Rules of Engagement (SROE) recognizes this inherent right (CJCSI 3121.01B, 13 June 2005). A mission may require a squad to charge an enemy machine-gun emplacement, but the rules on how to do so should never require an American to get shot at first!

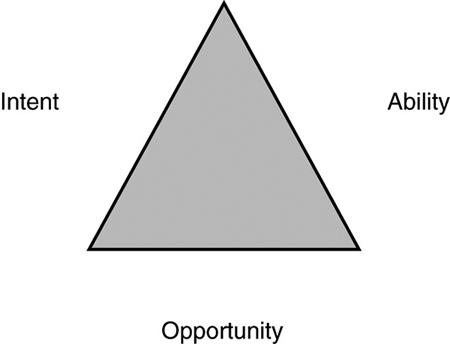

Nevertheless, before an individual can lawfully use deadly force in self-defense or defense of innocent others, he must be confronted with an individual or group that has demonstrated the hostile intent, ability, and opportunity to inflict death or grievous bodily injury upon himself or innocent others. The law enforcement model used to instruct on this concept is called the Threat Triangle.

We do not need to teach our soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines clairvoyant skills to divine hostile intent. In fact, a suspect’s subjective intent, legally and tactically, is not at all relevant. An insane person, or someone highly intoxicated on drugs or alcohol, may possess very little ability to formulate subjective hostile intent. Or as FBI Supervisory Special Agent John C. Hall, one of America’s foremost experts on the law of Use of Force, is fond of quoting, “Very little mentation is required for deadly action. A rattlesnake is deadly but could not form the mental state required for conviction of murder.”

Rather, at a minimum, we should be training our warriors on threat recognition as we train our cops, especially when sending them into uncertain environments where the threats are not wearing enemy uniforms. We should train them to recognize hostile acts and objective hostile intent.