The greatest praise must go to Rommel for his incredible ability, energy, and resource. He seemed to be at every part of the front, leading an attack here, guiding a column there, and it was due to his fierce drive that the offensive succeeded. He was now supremely confident. He had grasped the secrets and the tactics of desert warfare. Not only did he have the measure of the terrain but also that of his enemies. Now with adequate supplies he could advance and he made no secret of the fact that he planned the final objective to be the Suez canal.

On 9 April orders were issued to continue the pursuit of the British towards Tobruk with all possible speed, and 5th Light Division, with the reconnaissance battalion in the van, stormed eastwards leaving the Italians to carry out security duties around Mechili.

Tobruk - First Attack

With the first offensive concluded Rommel considered his next move and saw that this must be the capture of the port, fortress, and fleet base of Tobruk into the protection of which a great part of the hard hit but undefeated mass of the British desert force was undoubtedly moving.

There were only two alternatives. Either he could obey the orders of his superiors and go over to the defensive along the eastern borders of Cyrenaica, there to await the arrival of the main of his

Army before undertaking further operations, or he could continue his pursuit of the British enemy in the hope of bringing them to battle and of defeating them in the field before undertaking the advance into Egypt. Rommel considered the alternatives and the factors which would affect his decision and then came down on the side of the offensive. He would pursue the British and in a race to Tobruk might either enter the town and seize it from its weak garrison or enter it simultaneously with the British and in the resulting confusion .capture the place. But if he was to act offensively then he must act quickly and obtain men for this operation.

The mass of 5th Light Division was widespread across the desert's dusty face and some of its units were still lying stranded for lack of fuel in the desert south-west of Mechili. The Italian divisions had not yet caught up and, of 15th Panzer, only the motor cycle battalion and the anti-tank battalion were on their way to the front while the main of that division was still unloading at Tripoli.

With the decision to pursue the offensive, orders went out and behind a German advanced guard the main of Brescia Division left Derna on 8 April in an advance upon, and with the intention of, capturing Tobruk. Behind this advanced group the rest of 5th Light followed and then, in succession, the Ariete Division and those elements of 15th Panzer which had been able to join the column. By 9 April Gazala had been reached although strong British rearguards had frequently caused the column to halt, to deploy, and to take up attack positions. The advance continued all through the day and by evening had reached the 'White House', some 25 miles west of Tobruk. By now the pattern of life which the desert compelled upon those who lived in it had established itself. The interval between daylight and complete darkness in this climate is a very short one. Combat operations in the desert were usually halted, therefore, some time before the onset of darkness so that the troops could be fed, the vehicles serviced, defence positions allotted, and preparations for the morrow put in hand.

Those hours of darkness between the night of 9 and 10 April, had been used by the British to concentrate their forces on the approaches to Tobruk so that the German advance during the morning of 10th met determined and increasing resistance which brought it to a halt about 14 miles west of the town. Rommel, up with the forward troops and determined not to allow the tempo of the advance to falter, ordered the leading elements of Brescia Division into an infantry assault to clear the road but the attack failed in the heavy defensive fire which crashed down upon the two Italian battalions. During this unsuccessful assault the remainder of Brescia had closed up and Rommel, who had ordered the attack to be resumed on 11th, cancelled this when he realised through a personal reconnaissance how strong the British defences were around the town. Brescia then took up investment positions along the western front of the fortress between the coast and the high ground south of the road.

It was quite clear that until his reconnaissance Rommel had had no idea of how strong Tobruk really was and he seems not to have considered that the British would have improved upon the Italian fortifications and converted the town into a first-class defensive position. The British would find the supply problem less difficult to resolve for the Royal Navy controlled the seas, and the reinforcement and adequate provisioning and equipping of their troops in Tobruk could be carried out without too much interference from the Luftwaffe.

Tobruk had been designed by the Italians to be held by a garrison of divisional size but the population had risen to more than 36,000. It must be stated that more than two-thirds of that number were made up of non-combatant Corps and army troops, Arab refugees and prisoners of war. The actual fighting strength was between 10,000 and 12,000 battle-hardened veteran soldiers who were determined to hold out and to conduct an aggressive defence.

The physical defences of the town were two perimeters each defended by a belt of barbed wire and an anti-tank ditch. The confidence of the past months had allowed gaps in the wire and the ditches to remain open and therefore vulnerable although Australian infantry battalions had undertaken the task of preparing the defence and repairing the evidences of past neglect. The outer defensive belt extended nearly 30 miles across from west to east and nearly 9 miles inland from the sea. A douple row of strong points were set within the perimeter, laid out like a chess board and capable of giving mutual supporting fire. Most of these strong points had been prepared for infantry garrisons armed with machine guns and light anti-tank weapons. They were usually concreted with covered communication trenches and were hard to detect for they were not pill boxes standing upon the ground but sangars lying on, or just below, the surface.

The inner defence line was a small version of the outer and within the inner perimeter there were five miniature fortresses. The whole area was extensively mined and to aid the defence there was an airfield.

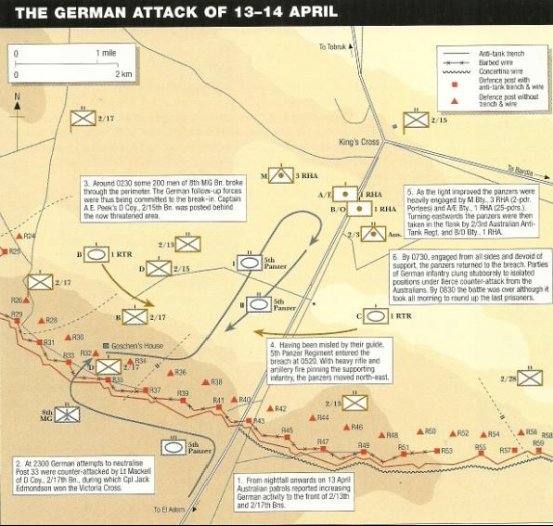

The battles to capture Tobruk fall into three phases. There were the reconnaissance probes on the 11 and 12 April, followed by the attacks from the southern front on 13th and 14th, and then from the south west on 16th and 17th.

When Rommel became aware of the strength of the place he realised that his troops helter-skeltering towards the town might dash themselves against the fortress and be destroyed piecemeal. He determined to throw an iron ring around the town quickly and intercepted the reconnaissance battalion and the anti-tank battalion as they headed eastwards. He switched them southwards and ordered them to pass round the British positions and to try to find a weak spot on the flanks. East of Acroma, artillery fire and extensive barbed wire defences brought the advance by the German troops to a halt. Rommel then gave orders to General Streich to swing further south and to advance upon El Adem. At that point there was a road up which his forces could drive and thereby enter Tobruk from the south. Streich pivoted his troops behind Brescia and moved to carry out his orders but sand storms and the usual inaccurate maps, together with poor navigation, so delayed his advance that he did not reach his objective until 11th. Local successes were scored against British patrols throughout the day but the main intent — to advance up the southern road - failed and the newly arrived panzer regiment, which then tried to force a passage on 12th, was brought to a halt by gun fire and an anti-tank ditch.