Bringing rebellion broached on his sword,

How many would the peaceful city quit

To welcome him!

‘The General’ must be the Earl of Essex, whose ‘Empress’—Queen Elizabeth—had sent him on an Irish campaign on 27 March 1599; he returned, disgraced, on 28 September. Plans for his campaign had been known at least since the previous November; the idea that he might return in triumph would have been meaningless after September 1599, and it seems likely that Shakespeare completed his play during 1599, probably in the spring. It appeared in print, in a short and debased text, in (probably) August 1600, when it was said to have ‘been sundry times played by the Right Honourable the Lord Chamberlain his servants’. Although this text (which omits the Choruses) seems to have been put together from memory by actors playing in an abbreviated adaptation, the Shakespearian text behind it appears to have been in a later state than the generally superior text printed from Shakespeare’s own papers in the 1623 Folio. Our edition draws on the 1600 quarto in the attempt to represent the play as acted by Shakespeare’s company. The principal difference is the reversion to historical authenticity in the substitution at Agincourt of the Duke of Bourbon for the Dauphin.

As in the two plays about Henry IV, Shakespeare is indebted to The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth (printed 1598). Other Elizabethan plays about Henry V, now lost, may have influenced him; he certainly used the chronicle histories of Edward Hall (1542) and Holinshed (1577, revised and enlarged in 1587).

From the ‘civil broils’ of the earlier history plays, Shakespeare turns to portray a country united in war against France. Each act is prefaced by a Chorus, speaking some of the play’s finest poetry, and giving it an epic quality. Henry V, ‘star of England’, is Shakespeare’s most heroic warrior king, but (like his predecessors) has an introspective side, and is aware of the crime by which his father came to the throne. We are reminded of his ‘wilder days’, and see that the transition from ‘madcap prince’ to the ‘mirror of all Christian kings’ involves loss: although the epilogue to 2 Henry IV had suggested that Sir John would reappear, he is only, though poignantly, an off-stage presence. Yet Shakespeare’s infusion of comic form into historical narrative reaches its natural conclusion in this play. Sir John’s cronies, Pistol, Bardolph, Nim, and Mistress Quickly, reappear to provide a counterpart to the heroic action, and Shakespeare invents comic episodes involving an Englishman (Gower), a Welshman (Fluellen), an Irishman (MacMorris), and a Scot (Jamy). The play also has romance elements, in the almost incredible extent of the English victory over the French and in the disguised Henry’s comradely mingling with his soldiers, as well as in his courtship of the French princess. The play’s romantic and heroic aspects have made it popular especially in times of war and have aroused accusations of jingoism, but the horrors of war are vividly depicted, and the Chorus’s closing speech reminds us that Henry died young, and that his son’s protector ‘lost France and made his England bleed’.

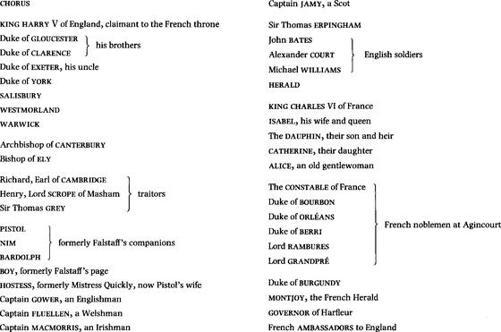

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

The Life of Henry the Fifth

Prologue Enter Chorus as Prologue CHORUS

O for a muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention:

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act,

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene.

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars, and at his heels,

Leashed in like hounds, should famine, sword, and fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraisèd spirits that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cock-pit hold

The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O pardon: since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million,

And let us, ciphers to this great account,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high uprearèd and abutting fronts

The perilous narrow ocean parts asunder.

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts:

Into a thousand parts divide one man,

And make imaginary puissance.

Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them,

Printing their proud hoofs i‘th’ receiving earth;

For ’tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there, jumping o’er times,

Turning th’accomplishment of many years

Into an hourglass—for the which supply,

Admit me Chorus to this history,

Who Prologue-like your humble patience pray

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play. Exit

1.1 Enter the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Bishop of Ely

CANTERBURY

My lord, I’ll tell you. That self bill is urged

Which in th’eleventh year of the last king’s reign

Was like, and had indeed against us passed,

But that the scrambling and unquiet time

Did push it out of farther question.

ELY

But how, my lord, shall we resist it now?

CANTERBURY

It must be thought on. If it pass against us,

We lose the better half of our possession,

For all the temporal lands which men devout

By testament have given to the Church

Would they strip from us—being valued thus:

As much as would maintain, to the King’s honour,

Full fifteen earls and fifteen hundred knights,

Six thousand and two hundred good esquires;

And, to relief of lazars and weak age,

Of indigent faint souls past corporal toil,

A hundred almshouses right well supplied;

And to the coffers of the King beside