Alcatraz –The Fortress

When the territories of Mexico were granted their independence from Spain in 1822, the Mexican Government inherited the land title for California. Despite the development potentials of Monterey and San Francisco, the government’s focus remained on developing the lowlands within the southern regions of California.

On May 13, 1846, when relations dissolved between the United States and Mexico, the U.S. Congress officially declared war against its southern neighbor. In June of 1846, John Charles Frémont and Kit Carson led an attack to seize a Mexican garrison in Sonoma, and declared California’s independence from Mexico. In their victory, they raised a makeshift flag with the claim seal entitled in bold print, The California Republic. The flag was made from white cotton sheeting fabric, with a broad strip of red flannel and a woven California Grizzly Bear, representing power and strength. The flag was later officially adopted by the territory, and is flown today as the state flag of California. Frémont also took Colonel Mariano Vallejo, one of the most respected Mexican military officers, as a prisoner. This event would go down in history as the Bear Flag Revolt.

Frémont and Carson continued their migration south, ultimately engaging in another attack, and taking the Mexican Fort in San Francisco. They again raised their flag, announcing the independence of the newly founded republic. Soon two United States warships arrived in San Francisco, and announced to Frémont and his men that the territories were now under martial law and that California was under jurisdiction of the United States. The Stars and Stripes were then raised over the flag of the California Republic. In another of his more notable acts, Frémont would also take credit for naming the Golden Gate. As he wrote in a personal memoir, he would christen the grand entrance to the bay Chrysopylae,or Golden Gatefor the same reason that the harbor of Constantinople was called Chryoceros,or Golden Horn.

John Charles Frémont, the disputed first governor of California, purchased Alcatraz Island for a mere $5,000 in 1846. As a military officer, Frémont recognized the strategic importance of the barren island as a potential site for military fortification.

Several years prior to the war, Mexico had passed legislation allowing governors to grant coastal land titles to Mexican citizens who would agree to develop the land. On June 8, 1846, the last Mexican Governor of California, Pio Pico, granted the title for Alcatraz to Julian Workman, a Mexican national. Workman had petitioned Pico for use of the island stating that “Alcatraces, or Bird Island, has never been inhabited by any person, nor used for any purpose,” and sought the right to develop the land. Alcatraz was granted to Workman under the sole condition that he “cause to be established as soon as possible a light, which may give protection on dark nights to the ships and smaller vessels which may pass there.” It is also documented that Workman never visited the island and never made any attempt to establish a lighthouse as he had agreed. In 1846, his son-in-law Francis Temple sold the island to John Charles Frémont, “in the terms of a bond for the purchase money in my official capacity as governor of California,” for the price of $5,000. The property was eventually conveyed to Palmer Cook & Company, but the money was never paid to Temple.

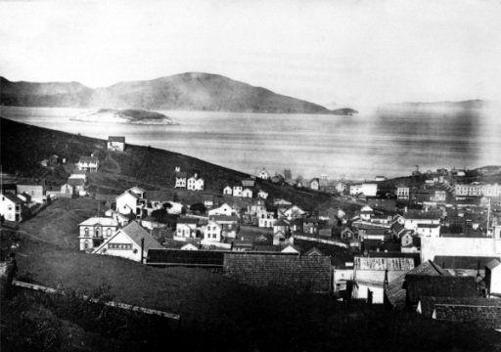

The earliest known photograph of Alcatraz, taken in 1853 from Nob Hill. This picture shows the island’s original topography, with soft desolate features, prior to any development or habitation.

United States Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a grandson of one the signers of the Declaration of Independence, eventually appointed Frémont, a man with strong political ambitions, as California’s Governor. However the U.S. Government disputed Frémont’s appointment, and later formally ruled that he did not have the authority to make purchases of land as an agent of the United States. Palmer Cook & Company eventually sued the U.S. Government, but they lost their case. The government insisted that even if the land had been rightfully purchased by Frémont, he had made the purchase under the name of the United States Government and therefore had no right to claim it. Frémont would later be court-martialed in Washington D.C., and his unauthorized purchase claims contributed to the trial verdict.

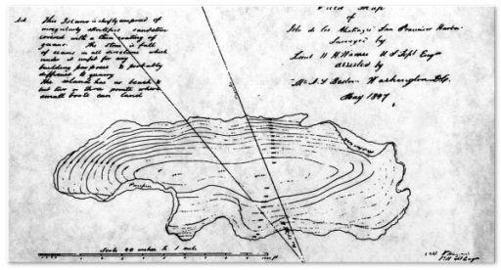

Despite these conflicts, Frémont did make the important observation that Alcatraz was strategically positioned to be a premier military fortification for the protection of San Francisco. Shortly after the signing of the peace treaty with Mexico in February of 1848, the United States Military took notice of the Rock and its strategic value as a military fortress. First Lieutenant William Horace Warner of the Corps of Topographical Engineers had begun conducting geological surveys on Alcatraz a year earlier in May of 1847. Warner was stationed out of Monterey under the command of Brigadier General Stephen Watts Kearny, who had been in the forefront of the dispute over Stockton’s appointment of Frémont as Governor.

Lieutenant William Warner’s 1847 Survey Map of Alcatraz.

The Gold Rush

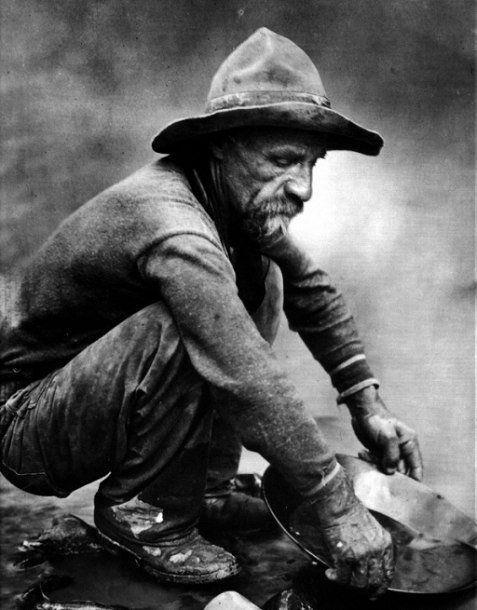

The discovery of gold in Coloma California in 1848 caused a worldwide frenzy and families from around the globe journeyed to the region with dreams of striking it rich. The population of San Francisco surged from four hundred in 1848 to thirty thousand by late 1849.

The California Gold Rush is remembered as an extraordinary episode in San Francisco’s colorful history and it also influenced the government to find the means of protecting its land claims from other powers. On a cold and crisp morning on January 24, 1848, mill carpenter James Marshall walked down a steep path to a river clearing where his crew was building a mill for John Sutter. Marshall wrote of what followed:

One morning in January – it was a clear, cold morning, I shall never forget that morning – as I was taking my usual walk along the river after shutting off the water, my eye was caught with the glimpse of something shining in the bottom of the ditch. There was about a foot of water running then. I reached my hand down and picked it up. It made my heart thump, for I was certain it was gold!

The tiny nuggets that Marshall had found that morning in Coloma, California had little value – their total worth was less than fifty cents. But Marshall’s discovery would change California history. Marshall’s find at Sutter’s Mill stirred little excitement from local newspapers and it was a Coloma general store owner named Sam Brannan who would become the mastermind behind the gold frenzy. Marshall told Sam about his find, and soon Brannan had collected several nuggets that he gathered into a small medicine bottle. Riding horseback into San Francisco along old Montgomery Street, he shouted to passing patrons, announcing his gold find in the American River. In January of 1848 the entire population of San Francisco was less than four hundred, but by the following year the populace would explode to over thirty-thousand and Brannan would become exceptionally wealthy from selling mining equipment to the new settlers.

As word spread around the globe of abundant riches in California, the United States Government would evoke security measures to protect its land and mineral resources from seizure by other countries. San Francisco developed into a principle port of U.S. commerce, second only to New York’s grand harbor. The incentive to safeguard San Francisco using the United States Military had now become a key priority. A commission was appointed to select sites for military fortifications, and Alcatraz seemed to be a strategic gift from nature.