Sir Francis Drake’s flagship, the Golden Hind.

In September of 1578, now traveling with only three ships, Drake sailed through the deadly Strait of Magellan, emerging dangerously into terrific Pacific thunderstorms. For two months the ships endured horrendous weather, unable either to sail out of the storms or to stay clear of the treacherous coastline. The ships were scattered and the smallest, the Marigold, went down with her entire crew. The Elizabethfound herself in the Strait once again and turned back for England. The Golden Hindhad drifted far to the south, ultimately sailing around the end of the South American continent and then plotting a northward course.

After stopping to make repairs off the coast of Southern Mexico, the Golden Hindsailed out of Spanish waters in April of 1579 and continued north along the California coastline. After nearly one and a half years of this journey, Drake was forced to bring the Golden Hindclose to shore for key repairs. The Hindwas a small, one-hundred-tonvessel carrying over thirty tons of Spanish treasure, which had been acquired through pirating raids and consisted mostly of gold and silver. The repairs required were so extensive that on June 17, 1579, Drake set up camp in an area south of Point Reyes California, now officially named Drake’s Bay. While waiting for the work to be completed, Drake spent five weeks exploring the interior region of the Marin coastline – yet he too failed to notice the inlet leading into the Bay of San Francisco, perhaps due to their inherit fog and inclement weather. Centuries later, historians are still passionately debating over Drake’s western voyage. The discoveries made on his North American expedition are poorly documented and only fragmentary records remain.

Much of Drake’s five-week respite on shore was spent interacting with native people. Francis Fletcher, the chaplain of the Hind, maintained a detailed journal of events throughout their expedition. He described the Indians at Drake’s Bay and their brave shore landings in their canoes. They approached Drake’s crew with peaceful gestures and welcoming gifts. Although there are no official records of Indians occupying the island of Alcatraz previous to its official discovery, there are some references indicating that the native Ohlone and Miwok Indians may have used the island as a fishing platform and it is almost certain that they were the first to explore Alcatraz by canoe.

In 1595 Sebastián Rodriguez Cermeño, another explorer searching for harbors along the California Coast sailed only twenty miles from the shores of the Golden Gate – but nevertheless he too failed to detect the clandestine bay. Although the details of his voyages are often disputed, numerous descriptions illustrate how he was forced to set anchor in Drake’s Bay during a heavy storm and subsequently lost his vessel the San Agustinwhich sank just offshore. The San Agustinwas carrying a cargo of porcelain ware, silks, wax and other trade goods, some of which were salvaged by the shipwrecked Spanish and were left onshore when they departed in a small launch that had been used to explore the coastal regions. Cermeño would make the first recorded use of the name San Francisco, misidentifying Drake’s Bay. He named the land the Bay of San Franciscofor the founder of his order, Saint Francis. The Cermeño expedition was termed a disgrace by his government and even his navigational charts would be considered suspect. In recent years, there have been several maritime artifacts discovered in this area that date from the same period, giving credence to modern theories of Cermeño’s landing and the wreck of the San Agustin.

In 1602, yet another Spanish explorer would lead an expedition to this region in search of a good shipping harbor. His name was Sebastían Vizcaíno, and his exploration would result in some of the most extensive chartings ever made of the northern coastline. Sailing with two vessels and a small launch for land expeditions, he departed Navidad and on the sixteenth of December landed in what he termed the “deepest harbor near land to lay anchor. ” He named the safe harbor for his Viceroy, the Conde de Monterey, and saw it as a profitable northern frontier port. He wrote that the magnificent harbor was rich with timber for shipbuilding, and a natural paradise with abundant shelter from wind. Despite these romantic tales of a harbor in Paradise, the new Viceroy of New Spain, Marqués de Montesclaros, did not trust Vizcaíno’s stories. A study written by Walton Bean, Professor of History at the University of California at Berkeley, suggests that the Viceroy’s distrust of Vizcaíno was so great that the expedition’s mapmaker, Martínez Palacios, was convicted of forgery and then hanged. San Francisco was destined to remain isolated and barren of discovery for nearly two hundred more years.

In New Spain, Jesuit missionaries had ruled the northwestern frontier regions dating back to late 1580, under the terms decreed by their King. These missionaries established settlements along the northern Baja peninsula, which were considered to be the most structured and disciplined of all the missions in New Spain. The Jesuits maintained their dominance in Baja until around the late 1760s, when the King ordered their expulsion, under suspicion that they would attempt to fragment the Spanish government and take power for themselves. The evictions of the Jesuits were delegated to Visitor-General Jośe de Gálvez, a special envoy of the King. His role was to conduct tribunals, and to restructure the political systems in various regions. Gálvez proposed to the King that a new governmental unit be established throughout the northwest. The new structure would be called a commandancy-general, and it was intended to expand Spanish territories up into the Californias. Gálvez claimed that the Europeans were starting to populate the northern lands beyond the Californias, and would soon begin a southward migration to establish their own rule.

In late 1768, Gálvez sent Captain Gaspar de Portolá on what he termed a “sacred expedition,” to establish colonies in the Californias. Father Junípero Serra, a catholic missionary, would accompany him to sanctify and establish the holy missions. Serra had been born in the village of Petra on the island of Majorca in 1713, the son of a poor farmer. His given name was Miguel, but he chose Junípero as his religious designation, naming himself for the closest companion of Saint Francis. Serra became a Professor of Philosophy at the University of Majorca, but left in his mid-thirties to pursue a more meaningful life as a foreign missionary. In Walton Bean’s fascinating interpretive history, the author described Serra:

“Through his life he was a vigorous, hard-driving man, never turning back from a task he had begun, always demanding the full measure from others as well as himself. In physical stature, Serra was short, not more than 5 feet 2 or 3 inches in height, but in courage and determination, he was a giant...”

Father Junípero Serra

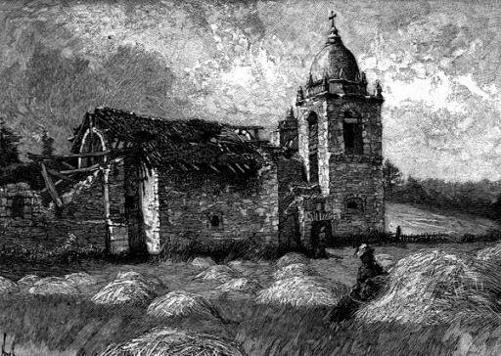

A period engraving of Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Rio Carmelo, founded in 1770.

Serra’s role in the colonization of California was most significant. He inspired the settler communities with missionary sermons that communicated divine principles and ethics. He would also establish the first Missions in San Diego (on July 16, 1769) and Monterey (which he founded on June 3, 1770, originally at what is known today as the Royal Presidio Chapel and then relocated to a site in Carmel in 1771, naming it Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Rio Carmelo). Father Serra died in 1784, and is buried in the Basilica at the Mission in Carmel.