Lakonia, Greece, January 2011

PICTURE CREDITS

1. Alexander the Great. The National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Alinari 23264. © Alinari Archives, Florence.

2. Olympias. Walters Art Museum inv. no. 59.2. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, acquired by Henry Walters.

3. Ptolemy I of Egypt. British Museum no. CGR 62897. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

4. Seleucus I of Asia. The National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Scala 0149108g. © 2010 Scala, Florence, courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali.

5. Demetrius Poliorcetes. The National Archaeological Museum, Naples. Scala 0149109g. © 2010 Scala, Florence, courtesy of the Ministero Beni e Att. Culturali.

6. A Lysimachan “Alexander.” British Museum no. AN 31026001. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

7. The Taurus Mountains. © Robin Waterfield.

8. The Acrocorinth. © Kathryn Waterfield.

9. The Temple of Apollo at Didyma. www.irismaritime.com.

10. The Arsinoeion. From A. Conze, Archäologische Untersuchungen auf Samothrake, vol. 1 (1875), pl. 54. © The British Library Board (749.e.4).

11. Indian War Elephant. © Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg.

12. Salamis Commemorative Coin. British Museum no. AN 3179001. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

13. The Lion Hunt Mosaic, Pella. Bridgeman 332175. © Ancient Art and Architecture Collection, Bridgeman Art Library.

14. Ivories from Vergina. © Ekdotike Athenon s.a.

15. Wall Painting from Vergina (detail). Bridgeman 60120. © Bridgeman Art Library.

16. The Fortune of Antioch. Vatican Museums. Scala 0041467M. © 2010 Scala Archives, Florence.

List of Illustrations

1. Alexander the Great.

2. Olympias.

3. Ptolemy I of Egypt.

4. Seleucus I of Asia.

5. Demetrius Poliorcetes.

6. A Lysimachan “Alexander.”

7. The Taurus Mountains.

8. The Acrocorinth.

9. The Temple of Apollo at Didyma.

10. The Arsinoeion.

11. Indian War Elephant.

12. Salamis Commemorative Coin.

13. The Lion Hunt Mosaic, Pella.

14. Ivories from Vergina.

15. Wall Painting from Vergina (detail).

16. The Fortune of Antioch.

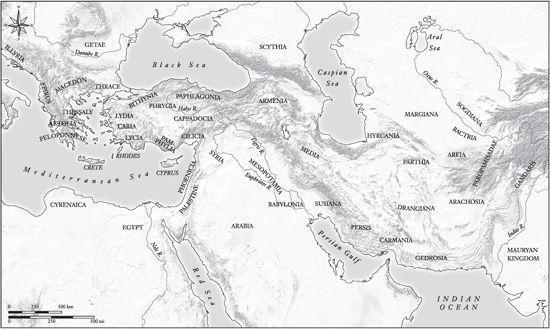

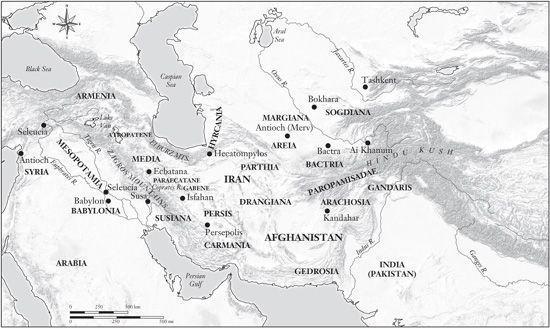

A. Alexander’s empire

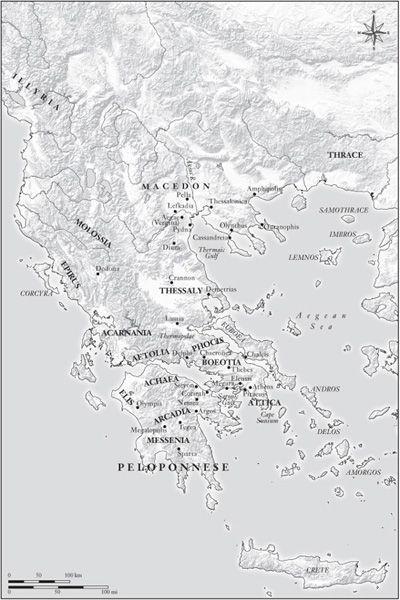

B. Macedon, Greece, and the Aegean

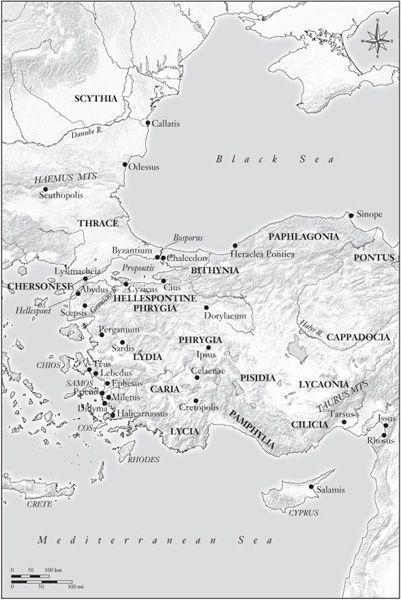

C. Asia Minor and the Black Sea

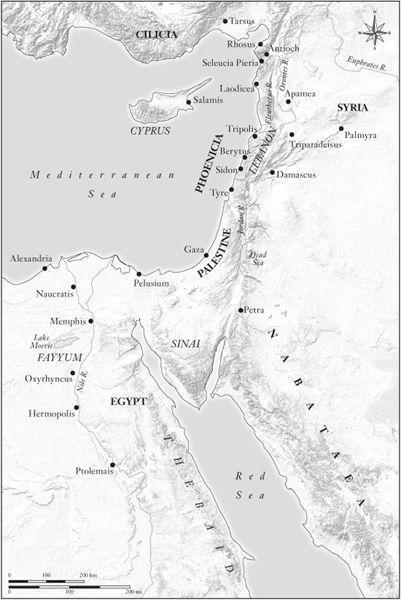

D. Syria and Egypt

E. Mesopotamia and the Eastern Satrapies

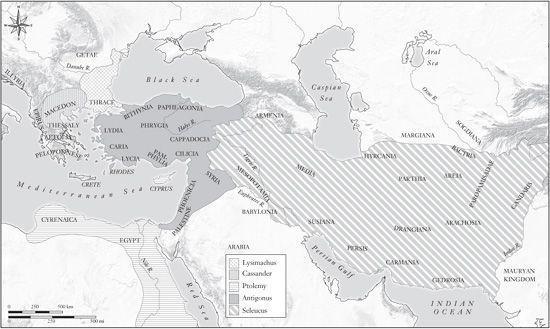

F. The Empire after the Peace of the Dynasts (311 BCE)

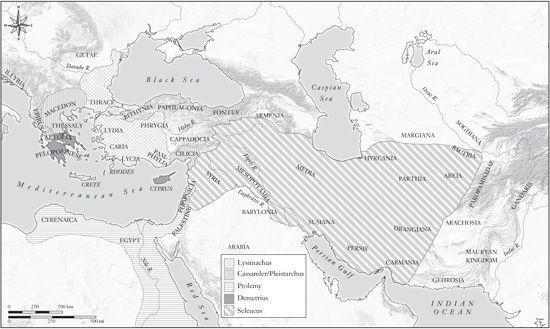

G. The Empire after Ipsus (301 BCE)

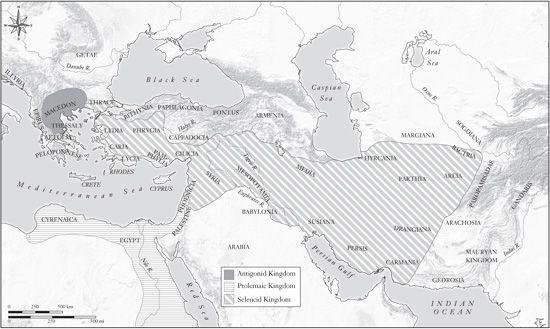

H. The Empire ca. 275 BCE

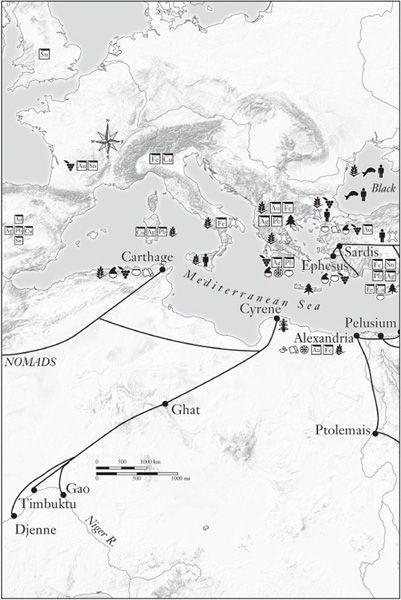

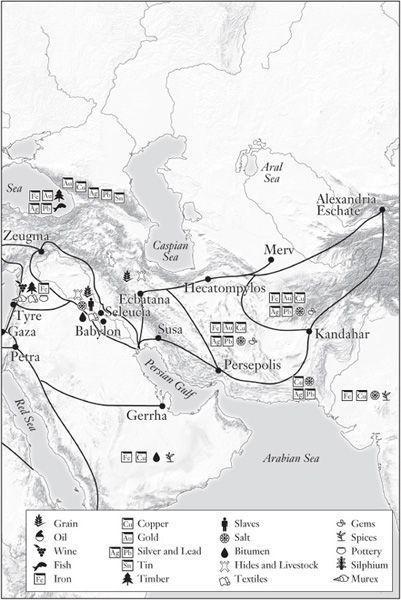

I. Roads and Resources

DIVIDING THE SPOILS

The Legacy of Alexander the Great

THE WORD SPREAD rapidly through the city of Babylon and the army encampments around the city: “The king is dead!” Bewilderment mingled with fear, and some remembered how even the rumor of his death, two years earlier in India, had almost provoked mutiny from the Macedonian regiments. They had been uncertain as to their future and far from home; their situation was not much different now. Would the king stage yet another miraculous recovery to cement the loyalty of his troops and enhance his aura of divinity? Or was the rumor true, and was bloodshed sure to follow?

Only two days earlier, many of his men had insisted on seeing him with their own eyes. They were troubled by the thought that their king was already dead, after more than a week of reported illness, and that for complex court reasons the truth was being concealed. Apart from rumors, all they had heard were the bland bulletins issued by Alexander’s staff, to the effect that the king was ill but alive. Knowing that he was in the palace, they had more or less forced their way past his bodyguards. They had been allowed to file past the shrouded bed, where a pale figure waved feebly at them. 1But this time there was no contradictory report, and no waving hand. As time passed, it became clear that this time it was true: Alexander the Great, conquering king and savior god, was dead.

At the time of his death in Babylon, around 3.30 p.m. on June 11, 323 BCE, Alexander was just short of thirty-three years old. He had recklessly exposed himself to danger time after time, but apart from war wounds—more than one of which was potentially fatal, especially in those days of inadequate doctoring—he had hardly been ill in his life and was as fit as any of the veterans in his army.

How had such a man fallen ill? True, there had been a lot of drinking recently, both in celebration of the return to civilization and to drown the memory of Hephaestion’s death (which, ironically, had been brought on or caused by excessive drinking). This boyhood friend had been the only man he could trust, his second-in-command, and the one true love of his life. But heavy drinking was expected of Macedonian kings, and Alexander had also become king of Persia, where, again, it was considered a sign of virility to be able to drink one’s courtiers under the table. If anyone was inured to heavy drinking, it was Alexander, and his symptoms do not fit alcohol poisoning. Excessive drinking, however, along with grief and old wounds (especially the lung that was perforated in India), may have weakened his system.

The accounts of his symptoms are puzzling. They are fairly precise, but do not perfectly fit any recognizable cause. One innocent possibility is that he died of malaria. He had fallen ill ten years previously in Cilicia, which was notorious for its malaria up until the 1950s. Perhaps he had a fatal recurrence of the disease in Babylon. 2More dramatically, the reported symptoms are also compatible with the effects of white hellebore, a slow-acting poison. The incomprehensibility of Alexander’s death to many people, and its propaganda potential, led very quickly to rumors of poisoning, especially since this was not an uncommon event among the Macedonian and eastern dynasties. And, as in an Agatha Christie novel, there were plenty of people close at hand who might have liked to see him dead. It was not just that some of them entertained world-spanning ambitions, soon to be revealed. It was more that Alexander’s recent paranoid purge of his friends and officials, and his megalomaniacal desire for conquest and yet more conquest, could have turned even some of those closest to him.

Now or later, Alexander’s mother stirred the pot from Epirus, southwest of Macedon. For some years, Olympias had been in voluntary exile from Macedon, back in her native Molossia (the mountainous region of Epirus whose kings, at this moment in Epirote history, were the de facto rulers of the Epirote League). On his departure for the east, Alexander had left a veteran general of his father’s, Antipater, as viceroy in charge of his European possessions for the duration of his campaigns—Macedon, Thessaly, Thrace, and Greece. Unable to be supreme in Macedon, and irrevocably hostile to Antipater, Olympias returned to the foundation of her power. But she never stopped plotting her return to the center. She was widely known to have been involved in a number of high-profile assassinations, and was a plausible candidate for the invisible hand behind the murder of her husband, Philip II, in 336, since it seemed as though he was planning to dislodge her and Alexander from their position as favorites.